Zervou Refugee Camp: Silence Is Not an Option for Greece’s Samos Island

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

One of the biggest and most costly construction projects on Samos in recent years is now open. I cycled around the completed site this past week. It is awesome in its scale (over 6 hectares) and is a dramatic addition to the island’s infrastructure. The new camp for refugees at Zervou comes with a 43 million price tag and can accommodate up to 3,000 refugees. Currently there are around 400 men , women and children inside. It is a closed camp with entrance and exit scrutinised between 8am and 8pm. A mini bus shuttle will take them into Samos Town for 1.6 euro one way. The camp has invested heavily in surveillance and security systems including magnetic identity cards, high security gates, cameras and drones all of which allows for close monitoring of the refugees.

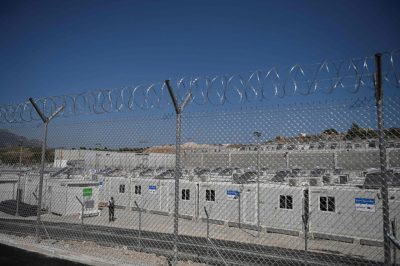

Being familiar from my work in the UK with prison design and function I can assure you with confidence that the Zervou camp has been designed along modern prison lines. But this is no low security prison. Enclosing the site behind double high meshed fences topped with razor wire is but one obvious sign of its intent. Just as the site itself, on the top of a hill in the middle of nowhere (10km to the nearest village) with not a shred of shade from the summer heat or the winter cold holds no comfort. It stands in stark contrast with the army barracks that cover the island where there are trees or gardens amongst the barracks which house the soldiers. At Zervou, all is grey, brutal and uniform – the cabins, the concrete roads and open areas and the endless wire. This is a deliberate design common to prisons where the physical lay-out is intended to convey clear messages as to its purpose to all those detained inside and those outside.

But Zervou is not a prison. It is a camp for refugees who have arrived in Samos to be cared for while they make their applications for asylum. They are not criminals but a wide range of vulnerable people from many societies seeking refuge and a future. “Zervou will be the first of the [new] planned hotspot camps on the Aegean islands. They all share a common characteristics: Due to their geographical location, they cut the camp residents off from access to the cities and their supply structures. And thus also from everyday life: from the light-heartedness of the cafés, from the liveliness of the marketplaces. But it is these places that enable people to forget, at least for a short time, that they are – or are supposed to be – refugees. “ (Samos: A place in the middle of nowhere Medico International, 21 Sept 2021).

The evidence is now overwhelming of the negative and inhumane consequences of detention in places such as Zervou. The impact of the camp’s isolated and remote location alone can be expected to have a severe impact on the mental health of already stressed and vulnerable people. We don’t need to waste time debating the evidence except to note that these truths are widely known but have little or no impact in shifting the practices of those in charge of such prisons.

For those of us who live on Samos the presence of Zervou is certain to pose challenges and problems. At the very least our biggest construction project in recent times will do little to enhance Samos’ reputation as a holiday destination. It is hard to see tourist buses stopping by. And there are certain to be those who will now think twice before visiting our beautiful island because of the cruelties experienced by refugees in places such as Zervou.

In that context, our silence is hardly an option. It will be interpreted by many as signalling consent to Zervou.

Places like Zervou illustrate the extent to which the EU policy of deterrence remains as a guiding principle in the treatment of refugees arriving on our shores. On no account make their arrival welcoming so that a clear message is sent of not being wanted. This has been a consistent feature of EU and Greece’s approach to the refugee challenge for many years now and shows no sign of shifting.

But as we are seeing with climate change things can and do begin to shift when the truth can no longer be ignored. As with EU refugee policies there is now mounting evidence that they fail on so many levels. The testimony of refugees, the reports of the NGOs working in the camps and countless academic and scientific accounts without exception all highlight the damage done to refugees who are incarcerated in such places. In a powerful critique of Zervou by MSF Samos they cite the experiences of their psychologists:

“As psychologists working with the people who are at the frontline of Europe’s tightening migration policies, we witness on a daily basis the deterioration of these people’s mental and physical well-being. The opening of the new prison camp is changing the collective identity of the refugees, their self-esteem and image: their dignity. Europe is breaking them.

What do you want us to say to a young boy who, even though has not committed a crime, is forced to remain locked up in a prison-like centre?” (MSF September 2021)

There is now growing evidence of the acute trauma and stress inflicted on refugees as they wait often for years in Greece whilst their asylum claims are processed. Isolated, cut off from Samos Town and incarcerated in a prison on a barren hillside is not going to make it any better. It is amazing that one of those responsible Manos Logothetis, from the General Secretariat for Reception of Asylum Seekers can claim that the new prison marks a decisive step in humanitarian care for refugees in that they now get a cabin with a kitchen and air conditioning (Euro News 23 Sept 2021) ? And he continued, “for the first time in the history of migration, a beneficiary will be able to sit in a restaurant that is air-conditioned and safe.” (Guardian 19 Sept 2021)

This is what Djina from Mali, who is now in the new camp had to say:

“We are here in the new camp, the containers are cosy but we didn’t come here to sleep. Some of us left their home two years ago. We haven’t any good food nor good health. We are prisoners, and nothing can replace freedom, so here it’s total traumatism.Also, the place is very isolated. They cut the financial aid, for them we are merchandise. The European Union is aware of everything. We can have 4 or 5 rejections. It’s weird here, don’t ask me any more.”

Ahmed from Iraq says:“I feel like I’m in prison. I feel lonely, lazy, and like I’m in another world. The new camp is definitely better than the tent, there is a bathroom, kitchen, water, electricity, refrigerator and air conditioners. But I stayed in the tent for three years, then now what, I moved to another camp? I ask myself these questions: how long will I be called a refugee? When will I become a human? A human who works, goes out, travels, does what any other person would do?(Both cited by Europe Must Act, October 11, 2021)

We on Samos cannot pretend that we don’t have a big prison now in our midst. A prison built for refugees and not convicted criminals brings shame to Samos even if there was little we could do to stop it. But at least we can speak up and express our concerns and demand a change. It does not have to be like this. On the Canary Islands empty hotels were turned over to arriving refugees with great success.

These are early days for Zervou. It is not at all clear how this prison is to be developed or deployed. But what we can be clear about is the threat it poses for the future of Samos if it comes to be closely identified by its relationship to a prison. There are many in the world now who know the truth of this and their numbers will grow. Can we remain silent?

“The new camp is not a good thing for Europe. I think it is criminal to criminalise us. It is a shame to keep people in such a situation. When they tell me, ‘Oh, we have a nice bed, we have a nice kitchen for you,’ I’m not concerned with a nice bed or a nice place to sleep. It’s about having the freedom to move around and live with others. I am not just speaking for myself, but for all those who live with me in the camp on Samos. “

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Samos Chronicles.

Featured image is from Samos Chronicles