Will the Ontario Labour Movement Return to Class Struggle as Austerity Deepens?

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

The Ontario labour movement is in deep crisis. Some impressive struggles aside, it has been staggering since the end of the great mobilizations of the 1990s. Given the labour movement’s historic role in leading and supporting progressive change, its current disorientation should be a matter of alarm to its members of course, but also to anyone concerned with countering the insatiable greed and social destructiveness of capitalism.

There is a tendency within the Canadian labour movement – reinforced as we head into Labour Day – to reduce this crisis to a lack of unity. But the content of ‘unity’ matters and is inseparable from the question of direction. Battles over jurisdictional claims are certainly destructive. However, in the absence of political struggle, calls for unity can also be used to silence criticism and block difficult debates over vision and strategy. It is the lack of such crucial debates – which inevitably come with some divisions along the way – that is perhaps most disturbing about the state of today’s labour movement.

Consider. In the 1930s, the great breakthrough in the American labour movement, which also shaped the Canadian movement, was the birth of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) and its principle of unionization across skills. But it only came alongside a difficult but necessary exit from the craft-based AFL (American Federation of Labor), a tectonic break that represented profound ideological and strategic differences. When the AFL and CIO came together again in the mid-1950s the ‘harmony’ it brought didn’t bring a stronger, more solidaristic movement. Rather, the newly unified federation, the AFL-CIO, oversaw four decades of stagnation and decline in U.S. unions accompanied by some of the most shameful undermining of working class struggles abroad.

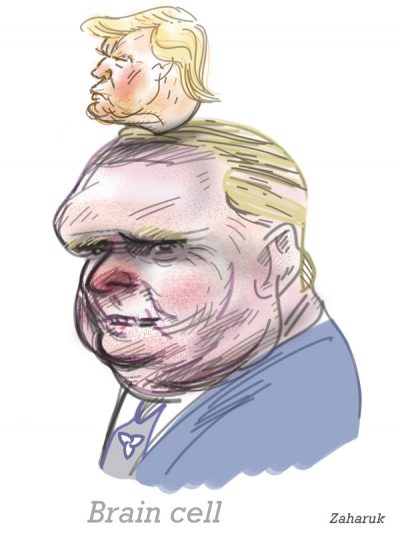

Conservatives on the Attack

With the election of the Progressive Conservatives led by Doug Ford, the threat of further, more damaging defeats as austerity gains traction is clear enough. Low-wage workers have already seen a freeze on the planned increases in minimum wages even as top executive compensation has increased by 50 per cent over the past decade. Very modest proposed increases in welfare benefits are also being cut, though income support benefits are lower today than a quarter of a century ago. And the already thin democracy in the administration of Toronto is about to get thinner with the radical unilateral trimming of the size of city council.

Coming soon are deep cuts to public spending in Ontario, which may well be much larger than anything attempted by the Conservative government of Mike Harris in the late 1990s. A combination of 4 per cent planned spending cuts, $7.5-billion in revenue cuts and $6-billion lost in accounting changes leaves a minimum of $22-billion to be hacked from public services by year three of the Conservative’s mandate.

Detailed reviews underway of government spending will set the stage for a massive attack on Ontario’s public sector. CUPE anticipates that in the hospital sector alone, 3,500 hospital beds and 16,500 staff would have to be cut to meet the target of eliminating $22-billion. In announcing a ‘line by line’ review of provincial spending the Conservatives referred to a commitment, not mentioned during the election, to reduce the province’s $315-billion debt. To significantly reduce Ontario’s debt, even over 20 years, would mean amputating public services.

Yet – and this is the most immediate sign of the crisis in labour – as the Conservatives prepare an onslaught of cutbacks, labour has been all but silent about how, beyond lamentations of another government turning to austerity, it will respond as a class. If that passivity continues, Ford’s Conservative government can be expected to read that as an invitation to go further and faster.

The challenge posed by the Conservative’s class agenda – tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, funded by cuts to public spending for working people – is to mobilize the working class in its own defense and in defense of the unemployed, the poor, the disabled, the young and the elderly, all of whom will be victims of the Conservative’s attack. Right-wing populism can only be defeated by exposing it and winning the support of the broadly defined working class, thereby deconstructing the Conservative base and forcing the Conservatives to retreat.

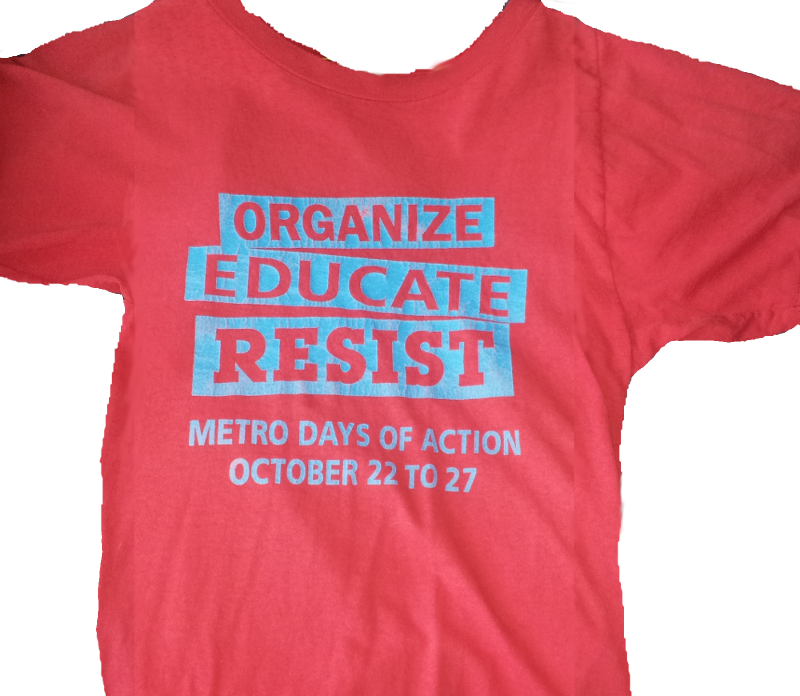

An obvious reference point here is the ‘Days of Action’, the dramatic class response that emerged in Ontario in the mid-90s to the radical neoliberal policies of Harris, when labour faced a comparable threat to the Ford cuts of today. Many young activists have little knowledge of the remarkable mobilizations undertaken by labour and its allies in that period. This makes it important to recall, by way of a brief overview, this suppressed historical memory.

Days of Action, Days of Possibilities

The Days of Action were a series of one-day city-wide protests, including one-day general strikes (by their very nature political strikes) that began in late 1995 and ultimately came to eleven Ontario communities over a two-and-a-half-year time span. The Toronto protest alone involved an estimated crowd of over 250,000.

In the 1990s, popular reaction against the ‘neoliberal’ undermining of social programs and attacks on the labour movement intensified across the core capitalist countries. In response, many European countries elected social democratic governments. The election of the NDP in Ontario, in 1990, preceded all of them. As elsewhere, this didn’t turn out as hoped. With the economy in recession, the NDP retreated from promises like socialized auto insurance and used state power to open and roll back public sector union contracts. The demoralization in the labour movement over this betrayal contributed to the election in 1995 of the hard-right Conservative government led by Mike Harris.

Harris acted quickly to implement his so-called ‘Common Sense Revolution’. One wing of the labour movement argued that there was no choice but to wait for the next election. This wasn’t convincing. The next election was far off and a good deal of damage, much of it seeming irreversible, would occur in the interim. In any case, the NDP’s performance in office had left it discredited even among former strong supporters – its’ vote had fallen by over 40% in 1995 and there was little enthusiasm for placing all of labour’s trust in the NDP again.

Against this, some labour and community militants called for a ‘general strike’. This had even less traction across the movement. The labour leadership’s strong aversion to this especially uncertain terrain was reinforced by an awareness that the kind of unity such a strategy demanded was simply absent. More important, since a good number of union members had for various reasons supported Harris, the labour movement could hardly claim a mandate for such a radical step.

In that sense, the strategy behind the Days of Action reflected the weakness of the labour movement as much as its strength. Nevertheless, the response brokered by the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL) among its often-fractious unions demonstrated the kinds of organizing capacities the labour movement still retained.

The OFL assigned key staff to work on the Days of Action full-time and to coordinate bringing both paid and voluntary organizers into each community well in advance of their actual day of action. Committed unions put their own staff and local activists to work reaching their members, some of whom grasped the threat and were quite ready to protest, but many who were unconvinced about either the issues or the tactics. Efforts to get members on side ranged from leafletting plants to training activists for one-on-one conversations, and in some cases carrying out mini-protests on specific issues to generate momentum. The preparations culminated in mass membership meetings in every workplace or local to get clear mandates for one-day strikes.

At the same time, OFL organizers and local union leaders began discussions at the community level with social movements, NGOs, and church groups around the core issues, with special concern to overcome long-standing suspicions of the union movement. This led to the formation of local coalitions, co-chaired by a trade unionist and someone from the movements (at least one of whom was to be a woman). The coalitions spoke to local groups and the media, wrote op-eds, bought radio ads, and also leafletted door-door (130,000 such leaflets were distributed in London, where the first Day of Action occurred).

Workplaces were shut down by workers, reinforced by cross-picketing (i.e. workers left their own work-sites to picket other workplaces, in part because shutting down your own workplace was illegal – though such legalities were in any case largely ignored). Schools were generally closed, not so much because of the teacher unions – whose attitudes were mixed – but by parents keeping their kids out, and by high school students themselves generally organizing the closing of their schools. At Oakwood Collegiate, for example, students went from classroom to classroom and got permission from each teacher to have some time to explain what the issues were and why a dramatic response was necessary. Thousands of workers were bussed in from nearby, and often distant, communities and mass marches took place, lined by hundreds of marshals to keep the march peaceful (and in Toronto by dozens of bands and singers along the route). The marches led into packed meetings in the largest spaces in the community, brimming with collective confidence and a newfound sense of social power.

To a degree not fully grasped at the time, even by those advocating the approach, the plan that labour had more or less stumbled into was strategically impressive and, given the defeat of the NDP and the absence of their support for extra-parliamentary political actions, politically bold.

- It allowed the unions supporting the action to focus their limited but solid core of organizers on one community at a time (something a general strike could not do).

- The announcements of the shutdowns a few months in advance resulted in a media frenzy warning of coming chaos in the community; this led workers to spontaneously and widely discuss the merits of the strategy.

- Because workers lost a day’s pay, they would only join the protest if won over to its necessity. That forced unions to convince their members to participate.

- Spreading the protests over an extended period of time kept the issue of the Harris cuts alive over a long stretch of time. This was something that waiting for the next election or pushing for a general strike (which at the time was likely to be short-lived) could not.

- The emphasis on shutting down workplaces for a day served the educational function of linking the Harris program to the corporate sector’s backing of the Harris assault on the poor, public services and union rights. It was also hoped that, fearing further workplace disruption, the corporations might push Harris to soften his agenda.

- Because the Days of Action were illegal walkouts any worker picketing her workplace could be fired. Unions therefore cross-picketed with, for example, postal workers shutting down auto plants and vice-versa. This created new worker solidarities at the very base of the working class movement.

- It brought community organizations, which had been very active at that time, into the mobilizations. This added significantly to the legitimacy of the protests and undermined charges that the Days were a self-serving union protest. As a gesture towards inclusiveness, the co-chairs of the broad coalitions in each community included one person from labour and one from the movements, with at least one co-chair having to be a woman. The mobilizations brought labour and social movements together, and within the social movements, provided a measure of coherence and strategic focus to its array of otherwise energetic but dispersed activities.

- The strategy could be effective even if not all unions participated. With municipal services interrupted, bus drivers shutting down transit, post offices and other government offices closed, and the most important manufacturing industry in the province, automotive, committed to the shutdowns, the message of broad and growing militant opposition within the labour movement was powerfully delivered. (That schools were also closed in spite of the vacillation of the teachers’ unions added to the sense of general community paralysis).

Three aspects of the Days of Action were especially noteworthy. First, though the protests against Harris had begun among the social movements, the centrality of the labour movement to social protest was confirmed. Only labour could effectively interrupt the daily functioning of workplaces and cities and the OFL proved especially adept at organizing these shutdowns. Second, this didn’t mean that the labour leadership could simply dictate the workplace shutdowns. Workers would only follow if they could be convinced that there were solid reasons to protest, that there was a credible plan of action with some possibility of success, and if they knew they wouldn’t be alone. Third, the Days were a reminder of the radical potentials of rank and file workers.

In this regard, the politicization of workers through the protests and strikes was repeatedly demonstrated. Workers moved organically toward larger more ambitious political perspectives: posing what kind of society they wanted to live in; consolidating a sense of solidarity across the working class; and recognizing that class is expressed in the community not just at the workplace. Workers were, often tentatively, sometimes with greater confidence, moving to a practice that might fit the label ‘class struggle unionism’.

But Was it Successful?

In measuring the outcome of the Days of Action, it’s useful to step back and look closer at the nature of unionized labour. Unions are organizations structured – ideologically and practically – around representing particular groups of workers within capitalism as they bargain with their employer or lobby the state. Though the boundaries of how unions do this get stretched from time to time this primary function has, over time, decisively shaped union cultures and practices.

To the extent that unions basically see themselves as ‘transactional’ – mediating a deal between workers and employers or the state – this has profound implications. For one, the fact that labour is not inherently a commodity but an expression of human creativity gets lost. For another, the focus is primarily on improvements in individual bargaining units, not the larger society and so the working class remains fragmented. And it is the immediate which dominates, not a seemingly remote vision. In good times, unions have proven able to make gains for their members through such a narrow unionism. But in bad times, this orientation leaves workers vulnerable as unions turn defensively inward. Neoliberalism has reinforced such inclinations within labour, as the drive to individualize and marketize tends to turn workers into consumers and unions into business-like institutions competing in labour markets.

Without a social vision, larger class perspective, or strategy for addressing the power of the state and not just the power of their particular employer, the reach and potential power of workers is restricted. Hence the defeats the union movement has experienced across a few generations now. This is the basis for American union organizer Jane McAlevey’s call for the fundamental importance of re-establishing a commitment among unions to ‘deep organizing’.

It was of course always naïve to expect that this kind of labour movement could suddenly burst through its structures and accumulated baggage and suddenly prove capable of defeating a recently elected anti-labour, anti-social government. The key issues in assessing the Days of Action and drawing future lessons therefore revolve around whether the Days gave workers confidence that fighting back – as opposed to passive acceptance – makes a difference, and whether they opened the door to building a stronger movement.

The answer is yes, they did. The Days of Action didn’t force the Harris government to fully reverse course but they did blunt his agenda. The threat to remove the right to strike in the public sector was stopped; likewise the attack on the interest arbitration system was halted, in the face of an illegal strike threatened by hospital workers; and social expenditures, which saw severe cuts at the beginning of the government’s term, were stabilized and in some cases reversed. In health care, for example, by 1997 expenditures in Ontario were growing significantly faster than they had been historically and far faster than they were in the final two years of the preceding NDP government. All this was significant and seen by the working class as victories.

Even more important, the Days introduced a new generation of workers and activists to organizing and politics. Suddenly, the union movement was a place to be, introducing young workers to the thrill of solidarity and exciting them with engagement in the larger questions of society. Slowly and unevenly and with varying degrees of clarity and confidence, this raised expectations and generated probing questions about what a different kind of labour movement might be.

But as the Days of Action ran out of steam, so did the other possible trajectories come to an end. Ultimately, the intimations of a revolution in trade union structures, culture, and strategies didn’t materialize. This was highlighted in two particular ways.

One was that after the demands of the labour movement were largely satisfied (for the time being at least) with respect to public sector spending and collective bargaining, the tents were folded up, even though the attack on other sections of society, like the poor and the disabled continued. The other was that no consideration was given to a plan that looked beyond the shutdowns. To take just one example: as the organizers left one community and moved to another, no organizational presence was sustained in the communities evacuated and typically no creative attempt was made to build new structures to carry on the battle in new ways.

This wasn’t just a failure of the labour leadership, though they certainly carry a good share of the responsibility. The members, on their own, didn’t grasp the importance of – or simply lacked the confidence and capacities to pursue – addressing the longer-term direction of their own and other unions.

Nor was the socialist left, in spite of its constant emphasis on transforming unions, able to do so. Once the labour leadership unilaterally decided to end the shutdowns, the left criticized the lack of democracy and broad consultation in how this decision was made and pressed for a step-up in militancy. But the left was itself far too disorganized and wedded to unproductive formulas to be able to use the opening created by the Days of Action to establish new connections to the working class, recruit activists to a larger vision, and effectively pose the transformation of unions as a condition for effecting and sustaining a more radical movement.

The sense in which the Days of Action ‘failed’ didn’t therefore lie in the fact that the Harris regime’s reforms laid the basis for the neoliberal politics that the Liberals sustained – defeating it totally was not possible – but that openings had occurred and the labour movement and its allies failed to build on them.

What has Changed in the Union Movement as we Face the Ford Regime’s Assaults?

History is a good teacher but former blueprints can’t simply be repeated. In drawing on the lessons of earlier experiences, sensitivity to what has changed is imperative. Four such changes seem especially significant with respect to the Ontario labour movement.

The first and most obvious is that even if the labour movement was not as strong then as often recalled, the defeats since have left unions in Ontario even more demoralized and disoriented and, moreover, more divided than ever. It will take some time and much effort to get the labour movement into active collective struggle.

A second difference lies in the pivotal role of the CAW (Canadian Auto Workers – the predecessor of Unifor). This involved the union’s presence in the key auto sector and its readiness and capacity to shut the industry down in the 1990s, and especially its role then in easing tensions between public and private sector unions. This critical union division revolved around the NDP’s intervention in public sector collective agreements. The CAW’s decision to maintain solidarity with the public sector ameliorated that split (though it made for sharp antagonisms between the CAW and some of the private sector unions who staunchly defended the NDP), and kept the public sector unions from being dangerously isolated by the rest of the labour movement.

Today, however, the leadership of Unifor is as distant from the public sector leaders as from those in the private sector, a division highlighted by, but extending beyond, Unifor’s departure from the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), Canada’s central labour body. Moreover, its economic clout and militancy has been eroded alongside the decline of Ontario’s manufacturing base as well as the union’s own response to that economic reality. This matters a great deal as there seems today to be no union ready and able to fill the strategic role the CAW played earlier. Reflecting the more general malaise in the labour movement today, where the OFL earlier rose to the occasion and became a place for debate and movement building, it seems to have drifted into operating more like a space where strategic discussion is laid to rest.

A third difference is that through the 1990s there was still an active growing complex of social movements leading a range of creative struggles. Today, however, with a few significant exceptions, this is no longer the case. But the popular frustrations that currently exist, especially among young people, are profound and potentially bursting into new political movements. As we’ve seen with regards to Sanders in the U.S. and Corbyn in the UK, in the right mix of circumstances and struggles, the energy and creativity of alienated young people can become a major political force even with barely developed institutional bases.

A fourth change is that the NDP, largely discredited when the Days of Action were initiated, has more momentum today. In their alignment with ‘third way’ politics in the 1990s, NDP leaders and functionaries looked with suspicion on the protests, seeing them as encouraging an alternative to electoral politics and also expecting that, if the party were to identify with and support the Days, this would hurt them electorally. Today, in contrast, sections of the party – having observed developments elsewhere – are less closed to positive engagement with any new round of protests. Indeed, given the fortunes of European social democracy, such alignments are seen by some (within limits of course) as necessary to survive electorally.

The point here, given the state of the Ontario labour movement, is to avoid framing the coming debate in the movement simply in electoral versus non-electoral terms. Electoral politics are clearly essential to struggles over the direction and ultimate transformation of the state. The issue is the vital importance of the labour movement not limiting itself to expressing its politics through the NDP and insisting on the need to include, in its overall strategy, the independent organizing and mobilizing of the working class.

As with the Days of Action, a strategy of waiting for the next election can simply encourage the government to hit harder and bring changes that may be extremely difficult to turn back. As experience in Ontario has shown, leaving politics to the politicians not only hurts electoral outcomes – elections depend on organizing informed grassroots activism well before any election campaign proper starts – but also removes a crucial check on what social democratic parties will do when elected.

What Now?

Socialist parties were once seen as distinct from other parties not just in their policies, but especially in their commitment to developing the capacities of the working class. Their emphasis was on education and cultivating among workers the ability to analyze, organize, debate, strategize and act collectively. In the absence of such a party, the weight for addressing this now falls on the unions. Whether they can take up this challenge is a central question to address in any sustained effort to take on the Ford government.

The reality of the current moment is that solidarity pacts or joint strategic discussions between unions are all too rare in Ontario and Canada today. In the context of the current divisions in the labour movement, with unified working class action a number of steps away, a starting point would be for unions to start addressing their own members. Internal plans should be developed – now – to disseminate information on the Ford government cuts and employer attacks and to, establish fight-back committees and train cadre to lead multiple discussions at every level of the union. Such discussions would include how to address what might be done to win workers over in our own workplaces (since not all are with us) much as is done in traditional unionization drives. This process could be extended to the community and begin to raise what kind of larger strategies seem necessary.

It is only out of such worker engagement within each union, and the ferment stimulated by trying to figure out how to overcome individual and workplace isolation and build effective resistance, that there is any chance for the inklings of solidarity across unions to start emerging and coalescing into something larger that might revitalize the overall labour movement.

Moving beyond such essential initial steps demands a strategic orientation that is now largely absent in each union. In the public sector, that orientation is clear. Public sector unions need to meaningfully re-establish their credibility in the general fight for social services. Public sector workers know what the impact of the cuts on services will be, and know how services can be improved and expanded. Public sector unions must back this by fully committing – whether in terms of resources, bargaining, campaigning or industrial action (work slowdowns, stoppages, work-ins, and the like) – to the defense, improvement, and expansion of public services and supporting any social groups joining that struggle. Only out of such creative and bold struggles will it become clear how vital it is for the public sector unions to go beyond their own struggles and come together in a common fight for public services and greater democratic control.

In the private sector, the issues are more complicated, since influencing individual jobs, levels of employment and security requires having some direct control over investment, capital flows and trade – issues that extend well beyond provincial jurisdiction (though this should not preclude workers acting more aggressively to block workplace closures or to argue for their socialization and conversion). An initial focus for forming the basis for such anti-neoliberal reforms might begin by taking advantage of new opportunities for major breakthroughs in unionization.

As the province reduces the number of inspectors and the regulation of workplace standards, and as corporations respond to legislated increases – like the substantial gains in minimum wages so inspiringly won through the Workers’ Action Center – by trying to recoup their costs through reducing worker benefits, forcing even greater speed-up, or manipulating the existing rules, the necessity of unionization increasingly surfaces. The message to the workers is straightforward: if you want higher standards, even ones you’re supposed to legally have, the only way to get and protect those standards is to unionize. The message to the labour movement itself is that – particularly in organizing the growing marginalized and precarious workforce – unionization must be understood as building the working class as a whole, not as an exclusive competition among unions for dues-paying members.

This implies not just a commitment of more resources, but a solidaristic strategy and must be insisted on as the only orientation to organizing that can meet the class attack that is coming from the Ford government. For example, in organizing franchise workers such as those at Tim Horton’s, where popular sympathies generally stand with the workers after the craven corporate counter-response to the increase in minimum wages, why wouldn’t every community with such a franchise should set up a community-based committee with organizers from every local union, gather contacts from union members with relatives or friends in the sector and move toward a province-wide unionization of the workers?

Other responses will depend on the pattern of Ford’s program of cuts and the government’s response to specific bargaining rounds. As that unfolds and particular unions act to challenge Ford’s attacks, it will be essential to recognize the strategic importance of these struggles to all coming struggles and organize solidaristic picket lines and whatever else might be demanded to advance the struggle.

All this is crucial in itself and also because it sets the stage for a strategy which, if not identical to the Days of Action, is based on the same systematic, gradually escalating, and comprehensive spirit of organizing political strikes that build momentum community by community.

Building for the Future

Building for the future can’t be postponed to ‘the future’. If people had, during the hectic and exciting Days of Action, raised the need for transforming our unions and creating new forms of permanent working class organizations in the community, this would no doubt have been treated as an abstract diversion. Too many more pressing issues were at hand. Yet it is that stubborn insistence on what is immediate – even if understandable at any particular moment – that has condemned the working class in Ontario (and Canada) to the exhausting treadmill of defensive battles. That legacy of repeatedly ignoring larger issues now sees workers and communities facing yet another round of assaults, this time even less prepared to respond.

Workers and unions desperately need to think larger and more long-term. This cannot be reduced to calls for ‘more militancy’, as important as that is. It begs the question: Militancy for what? What kind of society do we want, and what is our strategy for getting there? What kind of collective capacities and institutions do we need to build? And what does this all mean for transforming our unions?

The stakes couldn’t be higher. The wave of harsh austerity we will soon face may be more punitive than even the Harris government’s cutbacks. What was so important in resisting Harris and will now again be central is to recognize that we are under attack as a class and must think, strategize and fight back as a class. To be effective this must include preparing, organizing and mobilizing for political strikes – the attack is that significant.

Without the Ontario labour movement asserting a leadership role in fighting for dignity, equality, and social solidarity, it will continue to fade as a relevant social force. Without a vibrant labour movement, it is hard to imagine sustaining any mass, disciplined, and strategic fight-back; and without that, not only the distant future, but also tomorrow, looks grim. Unless the trade union movement rises to this challenge – not just in rhetoric, not just to defend its particular interests, but as a social force with a vision of a future that escapes the crippling mean-ness and inequality of capitalism, all working people will suffer.

Only the most serious commitment to organizing and mobilizing the working class in response brings the possibility of union revival (attend meeting in Toronto). And only that kind of ambition, with the class consciousness it brings and the grounded unity and class struggle it rests on, carries the antidote to the neoliberalism which has yoked us for decades.

*