Why Did the US and Its Allies Bomb Libya? Corruption Case Against Sarkozy Sheds New Light on Ousting of Gaddafi

Seven years after the popular uprising against Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi and the NATO intervention that removed him from power, Libya is extremely fractured and a source of regional instability. But while Congress has heavily scrutinized the attack on the American consulate in Benghazi a year after Gaddafi’s overthrow and death, there has been no U.S. investigation into the broader question of what led the U.S. and its allies to intervene so disastrously in Libya.

However, a corruption investigation into former French President Nicolas Sarkozy is opening a new window into little-known motivations in the NATO alliance that may have accelerated the rush to oust the Libyan dictator.

Last month, French police detained and questioned Sarkozy about illicit payments Gaddafi is said to have made to Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential election campaign. A few days after Sarkozy was released from detention, he was ordered to stand trial for corruption and influence-peddling in a related case, in which he had sought information on the Gaddafi inquiry from an appeals court judge. The scandal has highlighted a little-appreciated bind that Sarkozy faced in the run-up to the Libyan intervention: The French president, who took the lead among Europeans in the military campaign against Gaddafi, was eager to compensate for diplomatic blunders in Tunisia and Egypt and most likely angry about an arms deal with Gaddafi that went awry. Sarkozy, it now appears, was eager to shift the narrative to put himself at the forefront of a pro-democracy, anti-Gaddafi intervention.

Libya today is divided between three rival governments and a myriad of armed groups backed by external powers like the United Arab Emirates and Egypt. Security gaps have allowed terrorist groups to step up operations there and permitted a flow of weapons across the Sahara, contributing to destabilizing the Sahel region of northern Africa. The lack of political authority in Tripoli has also opened the door for the migrant crisis in Europe, with Libya serving as a gateway for migrants to escape Africa via the Mediterranean Sea. Although far fewer people have died in the Libyan conflict than in Iraq or Syria, the problems Libya faces seven years after NATO’s fateful intervention are no less complex, and often have more direct impact on Europe than what’s happening in Syria and Iraq.

A History of Corruption

The story of Sarkozy’s strange relationship with Gaddafi begins in 2003, when the United Nations lifted harsh sanctions against Libya that were imposed in the wake of the Lockerbie bombing.

After the sanctions were gone, Gaddafi looked to foster a cleaner, more legitimate image in Western circles. He found particularly eager suitors in British oil and gas companies, as well as Tony Blair, then the British prime minister, who saw lucrative business possibilities in the country. Libyan spy agencies also closely collaborated with MI6, their British counterpart, under the broad umbrella of counterterrorism.

Muammar Gaddafi and Nicolas Sarkozy

France was also developing a close business and intelligence relationship with Libya. In 2006, Gaddafi bought a surveillance system from a French company, i2e, which boasted about its close ties with Sarkozy, who at the time was France’s interior minister. In 2007, after he was elected president, Sarkozy received Gaddafi for a five-day state visit, Gaddafi’s first trip to France in over 30 years.

During the visit, Gaddafi said Libya would purchase $5.86 billion of French military equipment, including 14 Rafale fighter jets made by Dassault Aviation. Military sales “lock in relations between two countries for 20 years,” noted Michel Cabirol, an editor at the French weekly La Tribune, who has written extensively on arms sales.

“For Sarkozy, it was important to sell the Rafales because no one had sold them to a foreign country. In the case of Libya … it was one of his personal challenges at the time.”

Cabirol reported for La Tribune that negotiations were still ongoing in July 2010, but Sarkozy never did complete the sale of the Rafales to Gaddafi.

Revelations about the Libyan payments to Sarkozy surfaced in March 2011, when the specter of an imminent NATO intervention loomed large. Gaddafi first asserted that he paid Sarkozy’s campaign in an interview two days before the first NATO bombs were dropped. His son Saif al-Islam Gaddafi made similar claims shortly thereafter. In 2012, the French investigative news website Mediapart published a Libyan document signed by Moammar Gaddafi’s spy chief, Moussa Koussa, arranging for 50 million euros to support Sarkozy’s campaign, which French authorities later found to be authentic.

Since the initial revelations, Ziad Takiéddine, a French-Lebanese arms dealer who had helped arrange Sarkozy’s visit to Libya when Sarkozy was interior minister in 2005, has testified in court that he fetched suitcases stuffed with millions of euros in cash in Libya and delivered them by hand to Sarkozy in late 2006 and early 2007, when Sarkozy was still interior minister but preparing his presidential campaign. Sarkozy’s aide at the time, Claude Guéant (who became interior minister after the election), had opened a large vault at BNP in Paris for seven months during the campaign. The former Libyan Prime Minister Baghdadi Mahmudi has asserted in media interviews that payments were made. French authorities have also examined handwritten notes by Gaddafi’s oil minister, Shukri Ghanem, that detailed three payments totaling 6.5 million euros to Sarkozy.

Austrian police found Ghanem’s body in the Danube in Vienna on April 29, 2012, one week after the first round of presidential elections that the incumbent Sarkozy was contesting, and one day after Mediapart revealed the document signed by Koussa. The American ambassador to Libya at the time, the late Chris Stevens, wrote in an email to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in June 2012 that

“not one Libyan I have spoken to believes he flung himself into the Danube, or suddenly clutched his heart in pain and slipped silently into the river. Most believe he was silenced by regime members or else by foreign mafia types.”

One of the Libyans who is said to have organized the payments, the head of the Libyan investment portfolio at the time, Bashir Saleh, was smuggled out of Libya and into Tunisia by French special forces, according to Mediapart. Sarkozy confidante Alexandre Djouhri then flew Saleh from Tunis to Paris on a private jet shortly after Gaddafi was toppled. Saleh lived in France for about a year and reportedly met with Bernard Squarcini, head of France’s secret services, despite an Interpol arrest warrant against him.

“The judicial investigation shows that within the Gaddafi regime, Bashir Saleh had the most thorough records relating to French funding,” said Fabrice Arfi, one of two Mediapart journalists who has covered the affair since 2011. “He is suspected of having swapped the records for help from France to save him from the jaws of the revolution.”

Saleh in Paris (Source: Paris Match)

In 2012, Paris Match published a photograph showing Saleh walking freely in Paris despite the arrest warrant, and he was forced to leave the city. He flew to Johannesburg, where he has been living ever since. In March, shortly after his ally, former South African President Jacob Zuma, was ousted from power, Saleh was shot while coming back to his house from the airport in Johannesburg. Saleh is wanted for questioning in the Sarkozy affair by French judges.

Even Sarkozy’s successor, François Hollande, has implied that Gaddafi funded the Sarkozy campaign. In Hollande’s book, “A President Shouldn’t Say That,” while comparing himself to Sarkozy, Hollande wrote that

“as President of the Republic, I was never held for questioning. I never spied on a judge, I never asked anything of a judge, I was never financed by Libya.”

Sarkozy’s corruption in Libya is not the first time a French president or top political figure has received illicit funds in exchange for political favors. Indeed,

“Sarkozy’s corruption fits into a deeply ingrained, time-honored tradition in Paris,” said Jalel Harchaoui, Libya scholar at Paris 8 University. “In the 1970s, you had the scandal of Bokassa’s diamonds, which President [Valéry] Giscard accepted and took. You also have the “Karachi affair” involving kickbacks paid to senior French politicians via French weaponry sold to Pakistan in the 1990s. You also had Omar Bongo’s tremendous influence in Paris politics for years on end.”

Sarkozy and the Bombing of Libya

Sarkozy was an early and vocal advocate of the Western decision to intervene in Libya, but his real military zeal and desire for regime change came only after Clinton and the Arab League broadcasted their desire to see Gaddafi go and showed that they “wished to avoid the limelight,” said Harchaoui. The Arab League had suspended Libya on February 22, 2011, and in the following days, calls for a no-fly zone grew louder.

This “create[d] a framework in which France knows the war is likely to get initiated soon,” said Harchaoui.

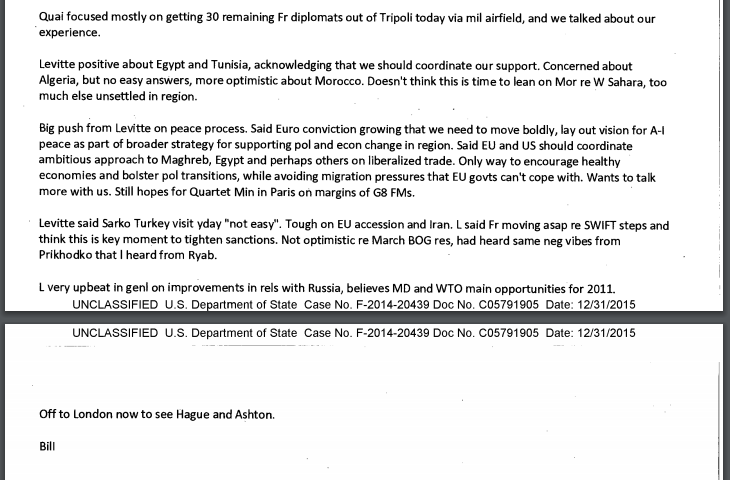

By February 26, William Burns, under secretary for political affairs at the State Department, had spoken with Sarkozy’s top diplomatic adviser, Jean-David Levitte. Burns reported in an email to Clinton’s team that “on Libya, French strongly supportive of our measures,” but that there were “Fr concerns on NATO role,” likely meaning that France didn’t want a full-blown NATO intervention at that point.

Source: Wikileaks

Two weeks later, Sarkozy made his first significant move to show that France, rather than being hesitant, had decided to take the lead in the fight against Gaddafi. On March 10, 2011, Sarkozy became the first head of state to recognize the National Transitional Council as Libya’s legitimate government. At the time, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte said recognizing the NTC was “a crazy move by France.” Crazy or not, France was now in the lead in Europe. According to a British parliamentary inquiry into the intervention in 2016,

“UK policy followed decisions taken in France.”

Sarkozy’s foreign minister at the time, Alain Juppé, then introduced United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which called for a no-fly zone over Libya, ostensibly in order to protect an impending massacre of civilians in Benghazi by Gaddafi. Although American diplomats drafted the resolution, Juppé was the Western diplomat who argued most passionately for it, telling the Security Council that “we have very little time left — perhaps only a matter of hours” to prevent a massacre against civilians in Benghazi. The French emergence to the front line of the diplomatic push was an apparent reflection of Barack Obama’s doctrine of “leading from behind” and letting Europe occupy the limelight. Arab League support for the resolution helped create a broad coalition of powers, beyond just the West, and the Libyan deputy ambassador to the U.N.’s defection against Gaddafi helped push the resolution forward.

Two days after the resolution passed, Sarkozy held a meeting at the Élysée Palace on May 19 to plan the military strategy with Obama, U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron, other NATO leaders, and leaders of the Arab League. According to Liam Fox, the British defense secretary at the time, the summit “finished mid-afternoon and the first French sorties took place at 16.45 GMT.” A gung-ho Sarkozy had sent 20 French jets to carry out the first sorties without informing Fox, four hours ahead of schedule; the U.S. and U.K. launched cruise missiles shortly thereafter. By showcasing the Rafale jets in the Libya campaign and other wars in Mali and Syria, France ended up attracting eventual clients in Egypt, India, and Qatar.

“Sarkozy has done a great job in getting the Rafale out there and hitting a convoy early on,” Reuters quoted a defense executive from a rival nation as saying at the time. “He will go to export markets and say this is what our planes can do.”

Why Sarkozy Went to War

Sarkozy’s zeal for military action stemmed from more than humanitarian concerns for rebellious Libyans in Benghazi who were endangered by Gaddafi’s wrath. Sarkozy’s reasoning included a mix of domestic, international, and personal reasons.

Sarkozy had found his administration out of step when the Arab Spring broke out in Tunisia. He had a strong relationship with Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, and when security forces fired on massive street protests in January, instead of condemning the violence, Sarkozy’s foreign minister offered to share the “savoir-faire” of France’s security forces “in order to settle security situations of this type.”

“Sarkozy’s image as a modern leader was sullied by the Arab Spring,” said Pouria Amirshahi, a former Socialist deputy in the National Assembly who in 2013 had called for a French parliamentary inquiry into the Libya intervention. The Libyan war allowed him “to forget his serious political mistakes during the Tunisian revolution of January 2011.”

Arfi, the Mediapart journalist, cautioned against treating Sarkozy’s involvement in the war as strictly personal, though it’s also a vital element.

“I don’t believe that Sarkozy brought France and other countries to war in Libya exclusively to whitewash himself,” said Arfi, who co-authored a book, “Avec les compliments du Guide,” which details the Gaddafi-Libya investigation.

But, Arfi said,

“It’s difficult to imagine that there wasn’t some kind of personal or private dimension to Sarkozy’s pro-war activism in 2011.”

The personal dimension that Arfi refers to would be Sarkozy’s interest in shifting the narrative that he had initially cultivated — as close to Gaddafi — to one that distanced him from the regime and any questions about his former proximity to Gaddafi, once he realized just how seriously the U.S. and Arab states wanted to get rid of the Libyan leader.

“Once the war was triggered, [Sarkozy’s] attitude is deeply impacted by the scandal that he is the only one aware of at the time. So, it gives rise to a very uncompromising France pursuing a scenario where everything would be destroyed and everything related to the Gaddafis would be discredited,” Harchaoui said.

However, Adam Holloway, a Conservative member of the British House of Commons who was on the Foreign Affairs Committee when it published its 2016 report on Libya, ruled out the personal angle, saying that

“if Mr. Sarkozy had taken money from Gaddafi, you might expect it to make him less likely to intervene, if anything. For this reason, I don’t really think this is a factor. … Indulging in regime change had nothing to do with intelligence (which should have said ‘Don’t do it’), but with David Cameron and Nicolas Sarkozy’s need to ‘do something.’”

For the Obama administration, the intervention in Libya was a humanitarian decision to stop Gaddafi from carrying out an assault against the besieged city of Benghazi. Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates wrote in his autobiography that

“Hillary threw her considerable clout behind Rice, Rhodes, and Power” and tipped the scale in favor of intervention.

Clinton, national security adviser Susan Rice, White House adviser Ben Rhodes, and U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power were instrumental in pushing the war forward; regime change was the goal regardless of Sarkozy’s personal relationship with the dictator.

“They were aggressive in pushing for the resolutions because they felt that they were the right thing to do. … It seemed a very realistic possibility that the regime was going to re-establish control throughout the country, particularly in eastern Libya, and if they did, there would be very harsh consequences for people deemed to be rebels,” said Libya historian Ronald Bruce St. John.

The “timing of the intervention was dictated by the move on Benghazi by Gaddafi’s armored column,” explained New Yorker journalist Jon Lee Anderson.

But civilian protection is not always enough to warrant a NATO intervention, as violent repression of protests in Bahrain and elsewhere in the Arab world have shown. The U.K. parliamentary inquiry found that there was little hard evidence that Gaddafi was actually targeting civilians in his campaign to take back cities held briefly by rebel forces. Gaddafi’s long antagonistic relationship with the U.S., the fact that there were no prominent Libyans advocating for him in the U.S., and the fact that Gaddafi didn’t have strong allies like Syria’s Bashar al-Assad does in Russia and Iran, made him an easy target to rally against, said St. John.

The French position was nonetheless notable. Rather than have a key ally oppose intervention, as France had done with the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, France was pushing hard for military action. A country that had previously acted as a partial brake on American intervention was now serving the opposite purpose of encouraging an intervention that turned into a catastrophe.

*

(Former deputy national security adviser Tony Blinken, Nicolas Sarkozy’s former diplomatic advisor Jean-David Levitte, former Director for War Crimes and Atrocities on the National Security Council David Pressman, former deputy chief of staff to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton Jake Sullivan, William Burns, and French Ambassador to the U.S. Gérard Araud all either declined to comment or did not respond when contacted for this article.)