Here’s Exactly Who’s Profiting from the War on Yemen

And how the U.S. could stop weapon sales if it wanted to.

Priyanka Motaparthy, a researchers for Human Rights Watch, arrived at a market in the Yemeni village of Mastaba on March 28, 2016, to find large craters, destroyed buildings, debris, shredded bits of clothing and small pieces of human bodies. Two weeks earlier, a warplane had bombed the market with two guided missiles. A Human Rights Watch (HRW) report says the missiles hit around noon on March 15, killing 97 civilians, including 25 children.

“When the first strike came, the world was full of blood,” Mohammed Yehia Muzayid, a market cleaner, told HRW. “People were all in pieces; their limbs were everywhere. People went flying.” As Muzayid rushed in, he was hit in the face by shrapnel from the second bomb. “There wasn’t more than five minutes between the first and second strike,” he said. “People were taking the injured out, and it hit the wounded and killed them. A plane was circling overhead.”

Saudi Arabia, one of the world’s richest countries, has been bombing Yemen, the fifth-poorest nation in the world, since 2015—with support from the United States. Their mission is to topple the Houthis, an armed political movement that overthrew Yemen’s president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, a Saudi ally, in February 2015. Saudi Arabia (a Sunni monarchy with an oppressed Shiite minority) feared that the Houthi movement in Yemen (who are Zaydis, a Shiite sect) was acting as an arm of its regional foe, Iran, in an effort to take power right across its southern border. While the Houthis have never been controlled by Iran, Iran delivers arms to the movement.

Under President Barack Obama’s administration and, now, President Donald Trump’s, the United States has put its military might behind the Saudi-led coalition, waging a war without congressional authorization. That war has devastated Yemen’s infrastructure, destroyed or damaged more than half of Yemen’s health facilities, killed more than 8,350 civilians, injured another 9,500 civilians, displaced 3.3 million people, and created a humanitarian disaster that threatens the lives of millions as cholera and famine spread through the country.

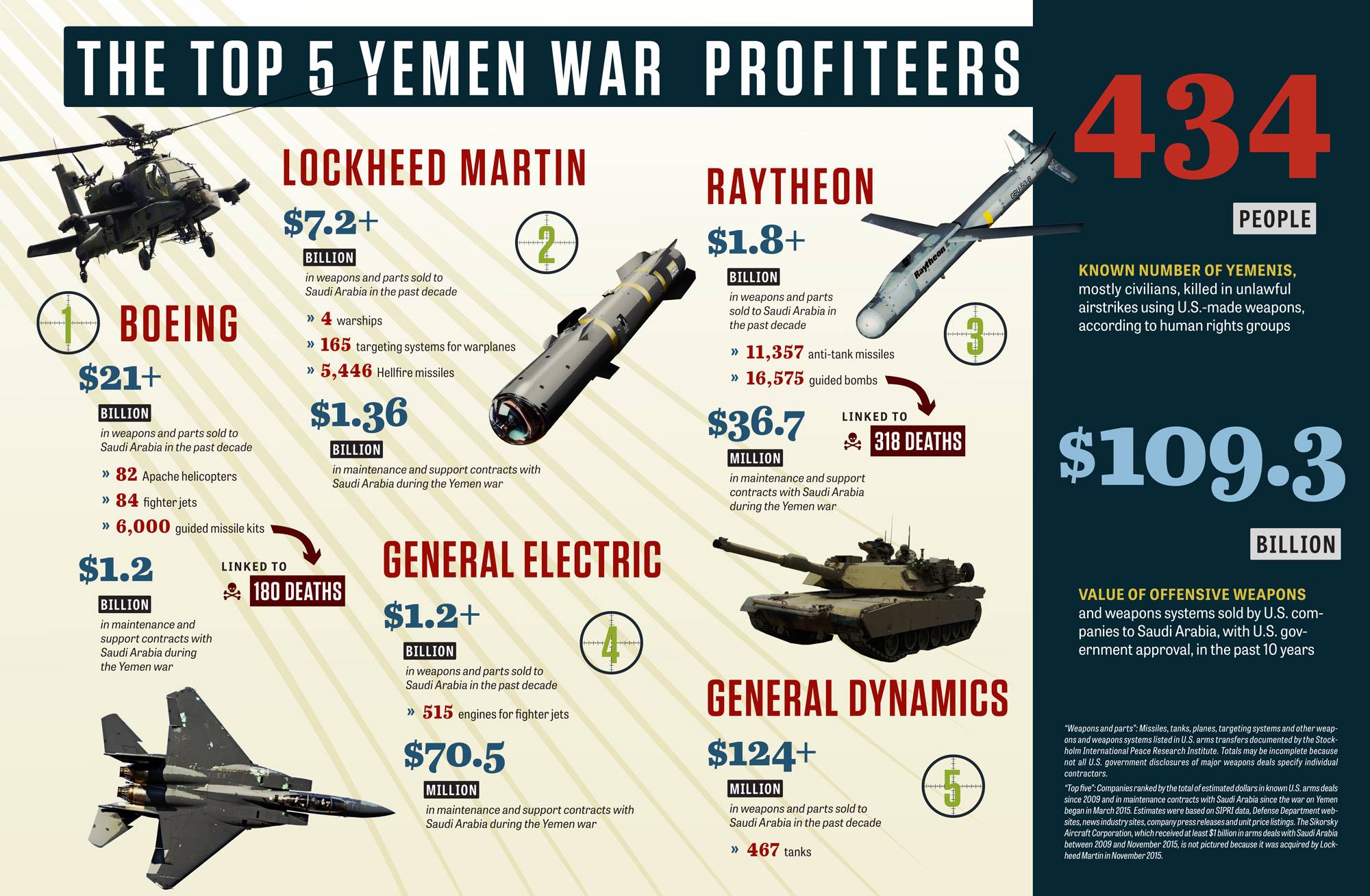

U.S. arms merchants, however, have grown rich. Fragments of the bombs were documented by journalists and HRW with help from Mastaba villagers. An HRW munitions expert determined the bombs were 2,000-pound MK-84s, manufactured by General Dynamics. Based in Falls Church, Va., General Dynamics is the world’s sixth most profitable arms manufacturer. One of the bombs used a satellite guidance kit from Chicago-based Boeing, the world’s second-most profitable weapons company. The other bomb had a Paveway guidance system, made by either Raytheon of Waltham, Mass., the third-largest arms company in the world, or Lockheed Martin of Bethesda, Md., the world’s top weapons contractor. An In These Times analysis found that in the past decade, the State Department has approved at least $30.1 billion in Saudi military contracts for these four companies.

The war in Yemen has been particularly lucrative for General Dynamics, Boeing and Raytheon, which have received hundreds of millions of dollars in Saudi weapons deals. All three corporations have highlighted business with Saudi Arabia in their reports to shareholders. Since the war began in March 2015, General Dynamics’ stock price has risen from about $135 to $169 per share, Raytheon’s from about $108 to more than $180, and Boeing’s from about $150 to $360.

Lockheed Martin declined to comment for this story. A spokesman for Boeing said the company follows “guidance from the United States government,” while Raytheon replied, “You will need to contact the U.S. government.” General Dynamics did not respond to inquiries. The State Department declined to comment on the record.

The weapons contractors are correct on one point: They’re working hand-in-glove with the State Department. By law, the department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs must approve any arms sales by U.S. companies to foreign governments. U.S. law also prohibits sales to countries that indiscriminately kill civilians, as the Saudi-led military coalition bombing Yemen did in the Mastaba strike and many other documented cases. But ending sales to Saudi Arabia would cost the U.S. arms industry its biggest global customer, and to do so, Congress must cross an industry that pours millions into the campaigns of lawmakers of both parties.

The Civilian Death Toll

Saudi coalition spokesperson Gen. Ahmed al-Assiri told the press that the Mastaba market bombing targeted a gathering of Houthi fighters. But because the attack was indiscriminate, in that it hit both civilians and a military target, and disproportionate, in that the 97 civilian deaths would outweigh any expected military advantage, HRW charged that the missile strikes violated international law.

According to an In These Times analysis of reports by HRW and the Yemeni group Mwatana for Human Rights, the Saudi-led coalition (including the United Arab Emirates [UAE], a Saudi ally that is also bombing Yemen) has used U.S. weapons to kill at least 434 people and injure at least 1,004 in attacks that overwhelmingly include civilians and civilian targets.

“Most of the weapons that we have found and been able to identify in strikes that appear unlawful have been U.S. weapons,” Motaparthy says. “Factories have been hit. Farmlands have been hit with cluster bombs. Not only have they killed civilians, but they have also destroyed livelihoods and contributed to a dire humanitarian situation.”

“The [U.S. government is] now on notice that there’s a high likelihood these weapons could be used in strikes that violate the laws of war,” Motaparthy says. “They can no longer say the Saudis are targeting accurately, that they have done their utmost to avoid civilian casualties.”

According to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the United States may not authorize arms exports to governments that consistently engage in “gross violations of internationally recognized human rights.” The Arms Export Control Act of 1976 stipulates that exported weapons may only be used for a country’s defense.

“When a country uses U.S.-origin weapons for other than legitimate self-defense purposes, the administration must suspend further sales, unless it issues a certification to Congress that there’s an overwhelming national security need,” says Brittany Benowitz, a former defense adviser for former Sen. Russ Feingold (D-Wis.). “The Trump administration has not done that.”

A Hundred-billion-dollar Client

Over the past decade, Saudi Arabia has ordered U.S.-made offensive weapons, surveillance equipment, transportation, parts and training valued at $109.3 billion, according to an In These Times analysis of Pentagon announcements, contracts announced on defense industry websites and arms transfers documented by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. That arsenal is now being deployed against Yemen.

Saudi Arabia’s precision-guided munitions are responsible for the vast majority of deaths documented by human rights groups. In These Times found that, since 2009, Saudi Arabia has ordered more than 27,000 missiles worth at least $1.8 billion from Raytheon alone, plus 6,000 guided bombs from Boeing (worth about $332 million) and 1,300 cluster munitions from Rhode Island-based Textron (worth about $641 million).

About $650 million of those Raytheon orders and an estimated $103 million of the Boeing orders came after the Saudi war in Yemen began.

Without these ongoing American-origin weapons transfers, the Saudi coalition’s ability to prosecute its war would wither. “We can stop providing munitions, and they could run out of munitions, and then it would be impossible to keep the war going,” says Jonathan Caverley, associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College and a research scientist at M.I.T.

The warplanes the United States delivers also need steady upkeep. Since the war began, the Saudis have struck deals worth $5.5 billion with war contractors for weapons maintenance, support and training.

“The Saudi military has a very sophisticated, high-tech, capital-intensive military that requires almost constant customer service,” Caverley says. “And so most of the planes would be grounded if Lockheed Martin or Boeing turn off the help line.”

“Just Piling Up of Stuff”

The U.S.-Saudi relationship has its roots in the 1938 discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s energy-for-security deal with the Saudi monarchy. Today, in addition to oil, U.S.-Saudi relations are cemented by a geopolitical alliance against Iran—and by weapons deals.

Arms exports accelerated under Obama. By 2016, his administration had offered to sell $115 billion in weapons and defensive equipment to Saudi Arabia—the most of any administration in history.

Those arms exports “used to be more of a symbolic thing, just piling up the stuff,” says William Hartung, director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy.

But experts also say selling the Saudis so many arms incentivized the Arab monarchy to use them in devastating fashion.

“If a country, like Saudi Arabia or the UAE, has no commitment to human rights—whether stated or in practice—it’s no wonder that those countries would eventually misuse U.S.-sold weapons by committing war crimes,” says Kate Kizer, the policy director of Win Without War. “The U.S. government should be assuming these weapons of warfare will eventually be used in a conflict, even if one isn’t going on at the moment.”

With the Saudi invasion of Yemen in 2015, the U.S.-Saudi arms pipeline became deadly. Despite reports that U.S. bombs were killing civilians, the Obama administration’s support for the Saudi war drew only muted criticism in Washington.

“It was Obama’s war, and there was a lot of reluctance in Congress to take this on, particularly among Democrats,” says Shireen Al-Adeimi, a Yemeni American activist and professor at Michigan State University. Still, advocates with groups like Win Without War, Just Foreign Policy and the Yemen Peace Project worked to raise public awareness of the war’s horrors, lobbying Congress and the White House.

In May 2016, Obama canceled the delivery of 400 Textron cluster bombs to Saudi Arabia. In December 2016, two months after a Saudi airstrike hit a funeral hall and killed more than 100 people in the Yemeni capital of Sanaa, he halted the sale of 16,000 precision guided bombs from Raytheon, a deal worth $350 million. Those two decisions accounted for only a fraction of overall arms sales to the Saudis, and the flow of most weapons continued unchecked.

Trump’s Big Photo Opp

When Trump took office in January 2017, he made it a priority to strengthen the U.S.-Saudi relationship, which had taken a hit after Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran. As part of that bid, Trump reversed Obama’s decision to halt the $350 million Raytheon order.

Trump’s first overseas visit, in May 2017, was to Saudi Arabia, a jaunt to strengthen the alliance against Iran and get Saudi Arabia to sign on to Trump’s plans for an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal. During that visit, the United States agreed to sell Saudi Arabia $110 billion in American weapons, with an option for a total of $350 billion over the next decade.

Trump boasted his deals would bring 500,000 jobs to the United States, but his own State Department put the figure at tens of thousands.

On May 20, 2017, Trump and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud presided over Boeing’s and Raytheon’s signings of Memorandums of Agreement with Saudi Arabia for future business. Raytheon used the opportunity to open a new division, Raytheon Saudi Arabia.

“This strategic partnership is the next step in our over 50-year relationship in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” Raytheon CEO Thomas A. Kennedy told shareholders. “Together, we can help build world-class defense and cyber capabilities.”

The ink was barely dry before $500 million of the deal was threatened by a bill, introduced by Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) in May 2017, to block the sale of bombs to Saudi Arabia. In response, Boeing and Raytheon hired lobbying firms to make their case.

In the end, five Democrats—Joe Donnelly (Ind.), Claire McCaskill (Mo.), Joe Manchin (W.Va.), Bill Nelson (Fla.) and Mark Warner (Va.)—broke with their party to ensure arms sales continued, in a 53-47 vote. The five had collectively received tens of thousands in arms industry donations, and would receive another $148,032 in the next election cycle from the PACs and employees of Boeing and Raytheon. Nelson and McCaskill pulled in $44,308 and $57,230, respectively. Weapons firms are aided by a revolving door with the Trump administration. Then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, a former General Dynamics board member, warned Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) that the Rand Paul bill would be a boon for Iran. Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan served as a senior vice president of Boeing prior to coming to the Defense Department, though it’s unclear whether he’s championed U.S.-Saudi arms deals.

The Wall Street Journal reports that, in 2018, State Department staff, voicing concerns about the war on Yemen, asked Secretary of State Mike Pompeo not to certify that civilian deaths were being reduced. Their concerns were overridden by the department’s Bureau of Legislative Affairs, which argued such a move could put billions of dollars in future arms sales in jeopardy. The bureau is led by Charles Faulkner, a former Raytheon lobbyist.

Congress Wakes Up

In October 2018, the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia took center stage in Washington, when Saudi agents murdered and dismembered journalist Jamal Khashoggi in their country’s consulate in Istanbul. Khashoggi, a Saudi Washington Post columnist, had been critical of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The murder forced Congress to reckon with Salman, who, as defense minister, had launched the Saudi war on Yemen alongside a vicious crackdown on human rights activists. Suddenly, leading members of Congress, including Graham and other defenders of the U.S.-Saudi relationship, were alarmed at the prospect of selling more arms to Salman.

“The Khashoggi murder really broke the dam on congressional outrage about what the administration’s conduct has been [toward Saudi Arabia],” says Kate Gould, former legislative director for Middle East policy at the Friends Committee on National Legislation.

This spring, the Senate and House passed a bill championed by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) requiring the United States to stop giving the Saudi coalition intelligence and to prohibit the in-air refueling of Saudi warplanes. It was the first time in U.S. history that both chambers of Congress invoked the War Powers Act, designed to check the president’s war-making powers by requiring congressional authorization to deploy troops overseas. Trump vetoed the bill on April 16.

Arms expert William Hartung says the current political climate makes new deals unlikely: “It’d be very difficult [right now] to push a substantial sale of offensive weapons like bombs. Anything that can be used in the war is probably a non-starter.”

Still, billions of dollars of approved weapons are already in the pipeline. If congressional anger at the Saudis wanes, the arms spigot could reopen.

In February, a bipartisan group of senators—including Graham and Chris Murphy (D-Conn.)—introduced the Saudi Arabia Accountability and Yemen Act of 2019, which would halt future sales of ammunition, tanks, warplanes and bombs, and suspend exports of bombs that had been given a prior green light.

Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) wants to go even further. In January, he introduced legislation that would ban all weapons exports to Saudi Arabia, as well as maintenance and logistical support. The bill has 29 cosponsors (most of them Democrats).

“The bottom line is: We know for a fact that they’re bombing school buses, bombing weddings, bombing funerals, and innocent people are being murdered,” McGovern told In These Times. “The question now is: Are we going to just issue a press release and say, ‘We’re horrified,’ or is there going to be a consequence?”

McGovern says that if a measure like his is not passed, “other authoritarian regimes around the world will say, ‘Hey, we can do whatever the hell we want.’”

To pass such bills, Congress members will have to muscle past the arms industry. In Lockheed Martin’s 2018 annual report, the company warned, “Discussions in Congress may result in sanctions on the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.” For Jehan Hakim of the Yemeni Alliance Committee, the ongoing war comes down to the influence of money in Washington.

“We talk to family back home [in Yemen] and the question they ask is, ‘Why? Why is the U.S. supporting the Saudi coalition?’” Hakim says. “Profiteering is put before the lives of humans.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This investigation was supported by the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting.

is a New York-based journalist who focuses on U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East.

contributed research and fact-checking.