When Will They Lift the Blockade? Iraq and Cuba

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

“When will they lift the blockade?”

A polite smile did not hide her deep anxiety.

She wasn’t Venezuelan, not Iranian, not Syrian, nor a citizen of other nations struggling under U.S.-imposed sanctions.

I had just reached Baghdad on one of my missions there during the 1990s. How that question haunted me. I grew to anticipate it on each encounter inside Iraq during successive visits to cover 13 grim years of embargo.

Gracious welcomes turned solemn as my hosts raised concerns about the siege. A perfectly reasonable question: Iraqis knew that U.N. Resolution 661, imposed October 1990, was an American- orchestrated war policy. As I’d arrived from the U.S. those greeting me hoped I might have some revelation to share.

“Hard to say” became my recurring, desolate reply.

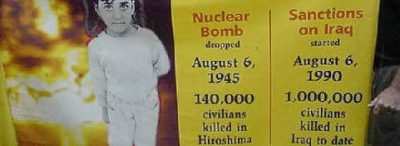

Relief looked more doubtful after April 1991 when U.N. Resolution 687 linking any respite to satisfactory removal of ‘weapons of mass destruction’ expanded the already exhaustive 661 sanctions regimen. Even as Iraq agreed to intrusive inspections– no nuclear arsenal was ever unearthed– suffering deepened, the death toll rose, deprivations mounted.

Year after year, I could offer little optimism for these essentially abandoned people. (Not to say doomed; not yet.) Neither the Clinton nor Bush administrations, nor the American public, nor the most liberal media hinted at even a slight opening in the sanctions-fortification.

The humanitarian and economic catastrophe that engulfed the nation remained largely concealed. Endless drama surrounding U.N. weapons inspections filled any news-time allocated for Iraq. Except for a steady flow of fearsome stories about Saddam Hussein.

The handful of anti-sanctions activists scattered across the globe managed to publish evidence of the calamitous consequences of that softly silent, deadly war. Despite those reports, outsiders remained woefully unaware, or unsympathetic– as Lawrence Davidson notes regarding Iran today.

So effective were threats against any extraterritorial embargo breach, no nation dared engage with Iraq. Even with Baghdad’s steady compliance to the terms of 661 and 687, the U.S. found additional reasons to continue the siege.

A decade passed. Finally, I revised my response to that wretched, heartbreaking query:

“Look at the embargo on Cuba”.

By 2000 this seemed a more realistic although still circumspect reply.

I’d avoided reference to the besieged Caribbean nation, already enduring four decades of sanctions. (A daring vote by Cuba against the U.N.-backed Gulf War should have directed Iraqi eyes in Cuba’s direction.) Anyway, would Cuba’s experience be relevant? Unlike Cuba, Iraq retained a fanciful attachment to putative oil revenues. It also clung to a farfetched prospect of accessing its foreign bank assets–at least for food and humanitarian essentials.

Unlike Cubans, Iraqis hadn’t driven out a colonizer, hadn’t overturned a dictator, hadn’t an alternative ideology to guide them. Iraq’s leadership, unchanged, presented a face not of victory but endurance.

Iraqis were naïve, or ill-informed, about how malicious and thorough modern-day blockades could be. Officials and citizens alike found comfort in a perhaps misplaced pride in 4,000-plus years of civilization. Iraq boasted its world-class doctors, scientists and artists, its many women professionals—as if they could overturn the assault. (Although year after year, their numbers would dwindle, lured abroad by America and its allies, all cognizant of Iraqi talent.)

Instead of mobilizing citizens to innovate and to study others’ experience (Cuba’s, for example), Iraq’s Baath leaders clung to the delusion that the blockade would be bearable and brief.

Although Iraqi troops had been ingloriously expelled from Kuwait –war crimes by the U.S. alliance in that military offensive are erased from history– the country’s leadership remained intact, ready to control any internal dissent.

What a contrast with Cuba! Unlike Iraq, after its revolutionary success, Cuba joined ideologically allied parties, organizations and nations similarly engaged in political struggle and socialist revolution. Concrete alliances resulted in solid support. Cuba’s military assistance to Angola and other African nations is legendary. As are its medical missions, with thousands of health professionals dispatched to nations in need (including Covid pandemic aid).

Cuba’s socialist commitment earned Russia’s alliance as an economic partner and erstwhile military protector. Iraq had no super-power ally. It lacked a single overseas partner, no Arab friend, no religious block, no overseas immigrant voices whatsoever. Whereas Cuba’s revolutionary achievement stirred people worldwide. It welcomed the arrival of countless delegations, offering firsthand testimony not of deprivation but of a worthy socialist model. Cuba’s arrangement with Canada, while limited, provided a route for American delegations to the island to witness its progress. Returning visitors joined a committed, effective anti-sanctions lobby. Their testimonials widened support for Cuba’s transformation.

Cuba’s U.N. diplomats made steady headway: by 1992, and annually thereafter, the U.N. General Assembly overwhelmingly voted in favor of a resolution condemning America’s embargo.

Cuba’s leadership had nothing remotely akin in Iraq. Fidel Castro’s wholesome, engaging character endeared him to many. The euphoria with which the Cuban president was greeted across the globe and by African Americans is well-known. Especially significant was his historic 1960 meeting with Malcolm Xdocumented by Rosemari Mealy.

One recognizes the prudence and dignity of both Castro brothers in President Díaz-Canel Bermúdez today. His July 17th response to Washington’s exploitation of recent public demonstrations in Cuba honors his predecessors.

Two embargoed nations: their experiences, strategies and circumstances couldn’t be more dissimilar. Iraq’s sanctions, killing untold numbers, ended with a massive military invasion whose disastrous outcome continues to unfold today, 31 years on.

Cuba’s policy was measured and resourceful. The country enjoyed wide international respect. It won successive U.N. endorsements, until, in 2015, the Obama administration signed a treaty with Cuba (only to be undone by Trump).

Today the nation, maliciously designated in 2017 as sponsoring terror, finds itself subject to extended sanctions under Biden. Whichever party rules Washington batters Cuba with this outrageous war plan. The media that endorse these policies permeate the American mind and shred its moral fiber.

Can Americans not understand others’ suffering, death and calamity without a spectacle of bombs and blood?

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on the author’s blog site, B. Nimri Aziz.

N Aziz whose anthropological research has focused on the peoples of the Himalayas is the author of the newly published “Yogmaya and Durga Devi: Rebel Women of Nepal”, available on Amazon.

Barbara is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from B. Nimri Aziz