When America Believed in Eugenics

Victoria Brignell investigates the History of Eugenics

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

Of relevance to the current debate on Eugenics and Depopulation, this article was first published in December 2010 in the New Statesman.

***

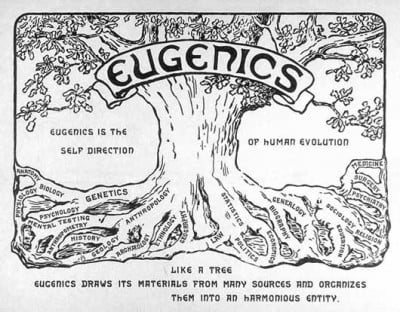

In the decades following the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species, a craze for eugenics spread not only through Britain but through America as well. Overbreeding by the poor and disabled threatened the quality of the human race, American campaigners warned. Drastic measures must be taken to avert a future catastrophe for humanity.

Amid popular fears about the decline of the national stock, one of the main drives behind the formation of American immigration policy at the end of the 19th century was the desire to exclude disabled people. The first major federal immigration law, the Act of 1882, prohibited entry to any ‘lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.’

As the eugenics movement gathered strength, the exclusion criteria were gradually tightened to make it easier for immigration officials to keep disabled people out of America. The 1907 law denied entry to anyone judged ‘mentally or physically defective, such mental or physical defects being of a nature which may affect the ability of such alien to earn a living.’ It added ‘imbeciles’ and ‘feeble-minded persons’ to the list of automatically excluded people and inspectors were directed to exclude people with ‘any mental abnormality whatever’. Regulations in 1917 included a long list of disabilities that could be cause for exclusion including arthritis, asthma, deafness, deformities, heart disease, poor eyesight, poor physical development and spinal curvature.

Detecting physical disabilities was a major aspect of the American immigration inspector’s work. The Commissioner General of Immigration reported in 1907: “The exclusion from this country of the morally, mentally and physically deficient is the principal object to be accomplished by the immigration laws.” Inspection regulations stated that each individual ‘should be seen first at rest and then in motion’ in order to detect ‘abnormalities of any description’. It was recommended that inspectors should watch immigrants as they carried their luggage upstairs to see if ‘the exertion would reveal deformities and defective posture’. As one inspector wrote: “It is no more difficult to detect poorly built, defective or broken down human beings than to recognise a cheap or defective automobile.” An abnormal appearance meant a chalked letter on the back – L for lameness, G for goitre, X for mental illness. Once chalked, a closer inspection was required, which meant that other problems were likely to be established.

Preventing disabled people immigrating to America was motivated by both economic and eugenic concerns. Officials wanted to keep out people considered likely to be unemployed and who might transmit their ‘undesirable qualities’ to their offspring. There was widespread support for this approach to immigration. In 1896, Francis Walker noted in the Atlantic Monthly that the necessity of ‘straining out’ immigrants who were ‘deaf, dumb, blind, idiotic, insane, pauper or criminal’ was ‘now conceded by men of all shades of opinion’ and indeed there was a widespread ‘resentment at the attempts of such persons to impose themselves upon us.’ William Green, president of the American Federation of Labor, argued that immigration restrictions were “necessary to the preservation of our national characteristics and to our physical and mental health”. A New York Supreme Court judge feared that the new immigrants were “adding to that appalling number of our inhabitants who handicap us by reason of their mental and physical disabilities.”

Disabled people born in the USA were as despised as disabled immigrants. A leading American-based scientist, Alexis Carrel, who worked at the prestigious Rockefeller Institute in the early years of the 20th century, advocated correcting what he called “an error” in the US Constitution that granted equality to all people. In his best-selling book Man, the Unknown, he wrote: “The feeble-minded and the man of genius should not be equal before the law. The stupid, the unintelligent, those who are dispersed, incapable of attention, of effort, have no right to a higher education.” Arguing that the human race was being undermined by disabled people, he wanted to use medical advances to extend the lives of those he deemed worthy and condemn the rest to death or forced sterilisation. He later praised Hitler for the “energetic measures” he took to prevent the contamination of the human race.

Carrel was not a lone maverick in America. His views were shared by large sections of the American population. While some scientists distanced themselves from him, much of America idolised him and welcomed his ideas. His book sold more than two million copies and thousands of people in America would turn up to hear Carrel’s talks, sometimes filling venues to capacity. He was even awarded the Nobel Prize.

Soon the White House itself was intent on restricting the right of disabled people to reproduce. President Theodore Roosevelt could not have been more blunt: “I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely from breeding; and when the evil nature of these people is sufficiently flagrant, this should be done. Criminals should be sterilised and feeble-minded persons forbidden to leave offspring behind them”. Theodore Roosevelt created an Heredity Commission to investigate America’s genetic heritage and to encourage “the increase of families of good blood and (discourage) the vicious elements in the cross-bred American civilisation”. Funding for the eugenics cause came from such distinguished sources as the Carnegie Institution and the WK Kellogg Foundation, and support also came from the influential leaders of the oil, steel and railroad industries.

In an effort to prevent unfit offspring from being born, sterilisation laws were introduced in many American states to stop certain categories of disabled people from having children. The first such law was passed in Indiana as early as 1907. This was 26 years before a similar law was introduced by the Nazis in Germany in 1933, The Law for the Prevention of Progeny with Hereditary Disease. In their sterilisation propaganda, the Nazis were able to point to the precedent set by the United States.

From 1907 onwards, many American men, women and children who were “insane, idiotic, imbecile, feebleminded or epileptic” were forcibly sterilised, often without being informed of what was being done to them. The German geneticist Fritz Lenz commented in 1923 that “Germany had nothing to match the eugenics research institutions in England and the United States”. He went on to castigate the Germans for “their backwardness in the domain of sterilisation as compared to the United States, for Germany had no equivalent to the American laws prohibiting marriage… for people suffering from such conditions as epilepsy or mental retardation”.

A landmark Supreme Court case in 1927 upheld America’s sterilisation legislation on the grounds it was necessary “to prevent our being swamped with incompetence”. Judge Holmes, reflecting in his judgement that our “best” citizens may be called on to give up their lives in war, said of sterilising the feeble-minded or insane: “It would be strange if we could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the state for these lesser sacrifices …It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind”.

By 1938, 33 American states permitted the forced sterilisation of women with learning disabilities and 29 American states had passed compulsory sterilisation laws covering people who were thought to have genetic conditions. Laws in America also restricted the right of certain disabled people to marry. More than 36,000 Americans underwent compulsory sterilisation before this legislation was eventually repealed in the 1940s.

America was not the only country in the Western world to introduce compulsory sterilisation of disabled people. Sweden sterilised 60,000 disabled women from 1935 until as late as 1976. Thousands of children labelled as having learning difficulties were sent off to live in “Institutes for Misled and Morally Neglected Children” where they were required to undergo “treatment”. When the extent of Sweden’s sterilisation programme came to light in the 1990s, some heartbreaking stories emerged. One woman was told that she would remain shut away in an institution for the rest of her life if she didn’t agree to be sterilised. She recalled crying as she was forced to sign away her rights to have a baby. Another man described how he and his teenage friends, terrified by the prospect of an operation, hatched a plan to run away. Other countries which passed similar sterilisation laws in the 1920s and 30s included Denmark, Norway and Finland. However, America led the way in promoting such a practice.

With such a prevailing culture, it is not surprising that some disabled Americans felt compelled to remain single voluntarily. According to a recent biography by Lyndall Gordon, the acclaimed American poet Emily Dickinson was epileptic. For this reason, Dickinson chose to spend the second half of her life as a recluse, refusing to leave her father’s house. In middle age, Dickinson had a passionate romance with a widower who wanted to marry her but she turned him down, regarding herself as unfit for marriage. People with epilepsy in America were warned against marrying for fear that sexual arousal might provoke seizures.

Following the first International Eugenics Conference in London in 1912, two more were held, in 1921 and 1932. Both were hosted by New York and both were dominated by America. At the 1921 conference, 41 out of the 53 scientific papers presented were written by Americans and the invitations were even sent out by the American State Department. At one stage, 375 courses covering eugenics were on offer at American universities including Harvard, Colombia and Cornell.

Not only did the American authorities take measures to stop disabled people immigrating, marrying or having children, but there are examples of American disabled people dying needlessly because society believed their lives were not worth living. In 1915 a leading Chicago surgeon Dr Harry Haiselden decided to allow a disabled new-born baby to die. This wasn’t the first time he had permitted a baby with an impairment to die, but no disciplinary action was taken against him. He was investigated three times by different legal authorities and each time they found in his favour. He was expelled from the Chicago Medical Society but only because he wrote newspaper articles about his work, not for his treatment of these children. Indeed, Haiselden received support from many prominent Americans and also won endorsements from some of America’s most well-regarded publications including the New York Timesand the New Republic.

In 1937, a Gallup poll in the USA found that 45 per cent of supported euthanasia for “defective infants”. A year later, in a speech at Harvard, WG Lennox argued that preserving disabled lives placed a strain on society and urged doctors to recognize “the privilege of death for the congenitally mindless and for the incurable sick”. An article published in the journal of the American Psychiatric Association in 1942 called for the killing of all “retarded” children over five years old.

After World War II, the Nuremburg court established by the Allies did not order reparations to be paid to the families of disabled people killed by the Nazis nor that those responsible be punished. German doctors accused of murdering disabled people defended themselves by claiming (with some justification) that they were only implementing ideas which had found support in other countries, including America.

What’s more, the Allied authorities were unable to classify the sterilisations of disabled people in Nazi Germany as war crimes because similar laws either did exist or had recently existed in America and other European countries. The new West German administration only provided compensation for people who had been sterilised against their will if they could prove they had been sterilised outside the provisions of the 1933 sterilisation law – in other words, if they could prove they were not genetically disabled. Following the defeat of the Nazis, compulsory sterilisation ended in Germany but it continued elsewhere in America and Europe. Only in the 1950s was the eugenic philosophy finally discredited in most countries.

There was no wholesale slaughter of disabled people in the UK and USA as there was in Nazi Germany. However, there are disturbing similarities in the history of these countries.

The widespread support given to eugenics in America and Britain shows that many people in these countries shared the values and ideology of the Nazis towards disability. Eugenicists in Britain and America like those in Nazi Germany believed it was socially desirable to prevent the creation of new human beings who might be physically or mentally disabled. Just as the Nazis set out to eliminate disabled people during the Holocaust, so the long-term aim of America’s sterilisation programme was to rid the country of people deemed to be “inadequate”. Although no formal mass sterilisation programme was implemented in the UK, an unknown number of forced or coerced sterilisations occurred in this country.

Forced sterilisation and mass killing are ethically different. But underlying both these measures was the presumption that there are people who are unworthy of life. The Nazis believed that disabled people’s lives had little value and wanted to relieve society of the burden of having to care for people they regarded as useless. We need to recognize that there was a time when such attitudes also received considerable support throughout America and Britain as well.

Social reformers in America and Britain wanted to create a perfect society, but the kind of society they envisaged contained an intolerant, illiberal, authoritarian dimension which allowed no place for disabled people. As Isaiah Berlin once put it, “Disregard for the preferences and interests of individuals alive today in order to pursue some distant social goal that their rulers have claimed is their duty to promote has been a common cause of misery for people throughout the ages.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Victoria Brignell works as a radio producer with the BBC. After reading classics at Downing College, Cambridge, she undertook journalism training at Cardiff University. She lives in West London and is 30 years old and is a tetraplegic wheelchair-user.