What China’s Devaluation Means to the U.S. Economy

Getty photographer Scott Olson arrested at Ferguson protest, 18 August 2014. (Ryan J. Reilly/@ryanjreilly)

Markets received a seismic jolt from China on Tuesday as it devalued its currency, the Yuan, by the most in two decades, cutting its daily reference rate by 1.9 percent. The move sparked instant selloffs in stocks, commodities, and emerging market currencies as well as a drop in the yield of the 10-year U.S. Treasury Note, which is trading early this morning at a yield of 2.16 percent.

The devaluation was interpreted in the markets as a sign of capitulation by China to forego a stable currency policy in a last-ditch effort to revitalize sluggish export growth. On Friday, China reported that its exports had plunged by 8.3 percent overall in July with dramatic declines of 12.3 percent to the European Union and 13 percent to Japan. Exports to the United States fell by 1.3 percent.

While China announced that the currency devaluation was a one-off move, the prevailing fear in global markets is that it marks a new round in the raging currency wars where countries are now competing to debase their currencies in hopes of making their exports more competitively priced in global markets.

The move spells trouble for the U.S. on a number of fronts. As of 8:39 a.m. in New York, stock futures on the Dow Jones Industrial Average were in the red by 147 points.

The U.S. imports more goods from China than any other country. Through June of this year, the U.S. had imported $226.7 billion in goods from China versus $150.4 billion from Canada and $145.1 billion from Mexico, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The Federal Reserve has been struggling to avoid importing deflation into the U.S.; this devaluation move now means that Chinese goods flowing into the U.S. just got cheaper and the ability of U.S. exporters to compete in global markets just got a lot harder.

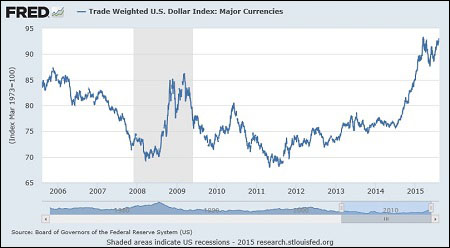

According to a Federal Reserve report released on July 17, the rising value of the U.S. Dollar is having a significant negative impact on large U.S. based multinationals. The report noted that “The dollar’s strength likely explains roughly a third of the recent decline in profits earned from foreign subsidiaries” and that “Firms with high foreign sales tend to be larger and account for almost 75 percent of S&P 500 nonfinancial earnings excluding oil and utilities.”

As we have reported before, this global currency race to the bottom cannot be solved by central banks. The problem is directly rooted in the unprecedented levels of income and wealth inequality that plague this era. In the U.S., that problem springs directly from Wall Street’s institutionalized wealth transfer system.