Were Top Managers at Neslté Connected to the Murder of a Colombian Union Activist?

Image: Luciano Romero, murdered Nestlé trade union activist.

This article was first published by WhoWhatWhy.

Switzerland’s highest court is about to decide whether top managers at Nestlé—by revenue the world’s largest food company—will be investigated in connection with the murder of a former employee in Colombia.

Paramilitary thugs tortured and killed trade union activist Luciano Romero in 2005—just before he was to testify at the Permanent People’s Tribunal on Nestlé’s corporate and trade union policies.

Lower Swiss courts have ruled against an investigation of the company despite recommendations from a Colombian judge, but his widow launched an appeal earlier this year to the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.

The death of Romero, who worked for Nestlé’s subsidiary Cicolac for twenty years, was an all too familiar reminder of the dangers faced by trade unionists in Colombia. Right wing paramilitary groups—often encouraged by public officials—have frequently attacked labor organizers.

Courageous Judge Forced into Exile

Romero’s case drew international attention when a Colombian judge sentenced his killers to prison—a rarity in a country where justice typically bows to political and economic power. And that judge, José Nirio Sanchez, said there should be further investigation—both at the local and international levels—into the role of Nestlé. But the judge himself was forced into exile in the United States after the ruling.

Image right: Judge José Nirio Sanchez in 2009 (photo: Adam Wright, Metropolitan Washington Council, AFL-CIO)

Judge Sanchez later said it was those who order the executions and put up the money—what he called the ‘intellectual” players—who are most to blame for the continuing violence. “Thus, these crimes will not stop, since the true perpetrators are not prosecuted,” he told the US House Committee on Education and Labor in 2009.

No Protection for Employees

The legal team for Romero’s widow in Switzerland and his Colombian trade union, Sinaltrainal, submitted a request to Swiss public prosecutors to look into Nestlé’s role in the death. They argued that executives at Nestlé are complicit in the murder because they did nothing to prevent the killing, despite being informed of death threats against him.

Worse yet, executives at Nestlé may even have known its representatives encouraged Romero’s murder.

The European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) joined the case, claiming that Nestlé managers knew of company representatives in Colombia with close ties to paramilitary groups. What’s more, ECCHR said, company managers referred to Romero as a “guerilla fighter” which, in Colombia, is tantamount to a death sentence.

Lots of Protection for Nestlé

In May 2013, more than a year after Romero’s widow and Sinaltrainal asked Swiss prosecutors to investigate Nestlé in connection with the killing, the request was denied. Prosecutors said such an investigation was precluded by a statute of limitations: too much time had passed since the murder. The Cantonal (District) Court of Vaud backed the prosecutors, leading to the Supreme Court appeal.

Lawyers for Romero’s widow have also accused the Swiss Prosecutors office of using formalities to delay proceedings—effectively running out the clock on the statute of limitations—in order to protect one of the country’s biggest companies.

Image: Aerial view of Nestlé’s headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland

“That would be the conclusion to make,” Annelen Micus, legal advisor at the ECCHR, told WhoWhatWhy. “It’s not common to deal with cases that way. If it’s looking like the prosecutors will not move forward with an investigation, they tend to announce that within a couple of months.”

This is not the first time Swiss prosecutors have refused to investigate accusations against Nestlé. They previously dropped a case against the company when it was accused of hiring a security firm to infiltrate and spy on a Swiss NGO, whose members were writing a book about Nestlé’s policies. The case eventually had to be heard in a civil court where, in January 2013, Nestlé was found guilty.

The current case against the giant food conglomerate is a test for a decade-old corporate responsibility law in Switzerland. According to Micus, the law allows Swiss courts to hold companies criminally responsible for things that happen to employees abroad. In the ten years it’s been on the books, it has yet to be used in a human rights case.

“It’s a chance to establish a standard of human rights due diligence,” Micus told WhoWhatWhy. A ruling in favor of the investigation could set a precedent for further cases.

Other Nestlé Employees Murdered

The appeal in the Romero case comes just months after Oscar Lopez Trivino, another Nestlé employee in Colombia, was murdered. Like Romero, he belonged to the Sinaltrainal trade union and according to some sources was the fourteenth active or former employee of Nestlé killed in Colombia since 1986—most of them Sinaltrainal leaders. Nestlé has acknowledged that seven of its unionized employees, as well as several white-collar employees, have been killed.

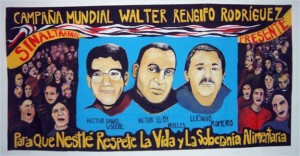

Image right: A banner commemorates some of the murdered trade unionists who worked at Nestlé.

Image right: A banner commemorates some of the murdered trade unionists who worked at Nestlé.

But spokesperson Philippe Aeschlimann told WhoWhatWhy that the company rejects all of Sinaltrainal’s accusations and says Nestlé provided security measures to union leaders, such as temporary relocation as well as increased security at their homes and at the union headquarters. “These were not designed to replace the State’s obligation to protect them,” Aeschlimann said, “but the union often rejected the offer of protection, arguing that the protection of their leaders was the responsibility of the Colombian government.” He also said: “Nestlé condemns all forms of violence. We have never used violence, nor have we associated with criminals. We have no responsibility whatsoever, directly or indirectly, neither by action nor omission for the murder of Luciano Romero.”

Labor rights activists will be closely watching the upcoming ruling by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland. Small wonder: Few means exist to protect those standing up for employee rights in countries with little “rule of law.” Holding companies to account on their home turf, in First World countries claiming to be civilized and decent, may be the best strategy.

Watch judge José Nirio Sanchez’ 2009 testimony before the US House Committee on Education and Labor (an English translator follows the Spanish statement).