Weapons Expert Dr David Kelly was Murdered

Why I know weapons expert Dr David Kelly was murdered, by the MP who spent a year investigating his death

By NORMAN BAKER – Last updated at 00:13am on 20th October 2007

For Tony Blair it was a glorious day. He was in the United States being feted by the U.S. Congress and President Bush.

Their adulation was such that he was being offered the rare honour of a Congressional Gold Medal.

Naturally enough, Bush and his administration were hugely grateful for Blair’s decision to join the United States in its invasion of Iraq.

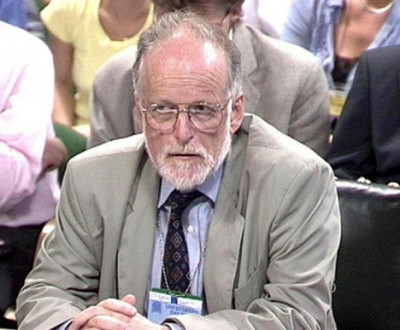

Under fire: Dr Kelly being quizzed by MPs

That invasion was supposed to lead to the discovery and disposal of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and make the world a safer place.

But as Blair was lapping up the grateful plaudits from the U.S. Congress on July 17, 2003, the man who had done more than almost any other individual on earth to contain the threat from WMD lay dead in the woods at Harrowdown Hill in Oxfordshire.

For Dr David Kelly, the UK’s leading weapons inspector, there was to be no adulation, no medal, no standing ovation.

His life ended in the cold, lonely wood where he was found the next morning, his left wrist cut open, and three nearly-empty blister packs of painkillers in his jacket pocket.

His death was, of course, sensational front-page news. Dr Kelly, unknown to almost everybody at the beginning of that July, had in recent days barely been absent from media headlines.

Much to his chagrin he had been thrust into the harsh glare of publicity, accused of being the mole who expressed to the BBC deep concerns about the Government’s “sexing up” of its dossier on weapons of mass destruction.

For Blair – accused of misusing, exaggerating or even inventing intelligence in order to justify the overthrow of Saddam Hussein – the stakes could not have been higher.

This was undoubtedly the greatest crisis of his premiership to date.

To add fuel to the flames, his director of communications, Alastair Campbell, had launched an unprecedented and vitriolic attack on the BBC, questioning its integrity and professionalism in the way it reported the story.

Suddenly finding himself under tremendous personal pressure, it seemed that Dr Kelly had buckled and decided to commit suicide.

That, at least, was the official version of events, as decided by the Hutton inquiry, set up by the Government with lightning speed within hours of Dr Kelly’s body being found.

The media, the political establishment, indeed almost everybody accepted Lord Hutton’s verdict. But the more I examined it, the more it became clear to me that Hutton’s judgment was faulty and suspect in virtually all important respects.

I was not alone in these suspicions. Letters began to appear in the press from leading medical specialists, in which they queried the suicide verdict.

The letters were well argued, raising profound and disturbing questions that remain unanswered to this day.

Increasingly concerned, I decided to give up my post on the Liberal Democrat front bench to look into Dr Kelly’s death.

My investigations have since convinced me that it is nigh- on clinically impossible for Dr Kelly to have died by his own hand and that both his personality and the other circumstantial evidence strongly militate against suicide.

Adulation: Tony Blair in Iraq

Given that his death was clearly not an accident, that leaves only one alternative – that he must have been murdered.

This is not a conclusion I have come to lightly. I simply set out to examine the facts, to test the evidence, and to follow the trail wherever it took me.

The account I give in this series may not be correct in all respects, but I suggest that it is rather more credible than the verdict reached by Lord Hutton.

I certainly believe there are enough doubts, enough questions, enough of a smell of stinking fish to justify re-opening this episode officially.

My investigations have been a journey into the unknown, and one that has taken many peculiar turns. Perhaps the most sinister came soon after starting my inquiries last year.

After writing a newspaper article outlining my early concerns, I found myself on a train speeding towards Exeter to see a man who had agreed to meet me only on condition of anonymity and after some rather circuitous arrangements.

These involved much complicated use of public telephone boxes to minimise the chance that his contact with me could be traced.

Finally, we talked over a glass of wine in a rather nondescript club.

He told me that he had recently retired but had connections to both the police and the security services, a claim which I subsequently verified through careful checks.

Like me, he had many doubts about the true circumstances surrounding Dr Kelly’s death and he had begun making his own surreptitious inquiries around Southmoor, the Oxfordshire village which was Dr Kelly’s home.

Posing as a freelance journalist, he had attempted to contact the key policemen involved in investigating the case. In this he was unsuccessful but within an hour he received an unexpected return call.

The person on the other end of the line did not bother with formalities, but instead cut to the quick. How would my contact welcome a full tax inspection of his business, VAT, national insurance, the lot?

Life could be made very difficult, he was told. How did he fancy having no money?

Naturally, this prospect did not appeal, and there he left matters until, at a wedding, he chanced upon an old friend whom he described to me initially as a very senior civil servant, but later as a “spook” from MI6.

He told his friend of his interest in the Kelly affair and also of the threatening phone call he had received.

His friend’s reply was a serious one: he should be careful, particularly when using his phone or his computer. Moreover, he should let the Kelly matter drop.

But my contact did not do so. Two weeks later he met his friend again, this time in a pub, and pressed him on the matter.

>{? His friend took him outside, and as they stood in the cool air, told him Dr Kelly’s death had been “a wet operation, a wet disposal”.

He also warned him in very strong terms to leave the matter well alone. This time he decided to heed the warning.

I asked my contact to explain what he understood by the terms his friend had used. Essentially, it seems to refer to an assassination, perhaps carried out in a hurry.

A few months later, I called my contact to check one or two points of his story. He told me that three weeks after our meeting in Exeter, his house had been broken into and his laptop – containing all his material on Kelly – had been stolen. Other valuable goods, including a camera and an LCD television, had been left untouched.

It was sobering to be given such a clear indication that Dr Kelly had been murdered, but the scientist himself appears to have been fully aware that his work made him a target for assassins.

British diplomat David Broucher told the Hutton inquiry that, some months before Dr Kelly’s death, he had asked him what would happen if Iraq were invaded.

Rather chillingly, Dr Kelly replied that he “would probably be found dead in the woods”.

At the inquiry, this was construed as meaning that he had already had suicidal thoughts. That, of course, is patently absurd.

Nobody can seriously suggest that he was suicidal at the time the meeting took place – yet Lord Hutton seems to have made his mind up about the way in which DrKelly died before the inquiry even began.

The result is a series of gaping, unresolved anomalies.

Crucially, in his report, Hutton declared that the principal cause of death was bleeding from a selfinflicted knife wound on Dr Kelly’s left wrist.

Yet Dr Nicholas Hunt, the pathologist who carried out the post-mortem examination on DrKelly, stated that he had cut only one blood vessel – the ulnar artery.

Since the arteries in the wrist are of matchstick thickness, severing just one of them does not lead to life-threatening blood loss, especially if it is cut crossways, the method apparently adopted by DrKelly, rather than along its length.

The artery simply retracts and stops bleeding.

As a scientist who would have known more about human anatomy than most, DrKelly was particularly unlikely to have targeted the ulnar artery. Buried deep in the wrist, it can only be accessed through the extremely painful process of cutting through nerves and tendons.

It is not common for those who commit suicide to wish to inflict significant pain on themselves as part of the process.

In Dr Kelly’s case, the unlikelihood is compounded by the suggestion that his chosen instrument-was a blunt pruning knife.

This would only have increased the pain and would have failed to cut the artery cleanly, thereby hastening the clotting process.

Statistics bear out the extremely low incidence of individuals dying by cutting the ulnar artery, with only one recorded case in Britain during the entire year of Dr Kelly’s death.

Year long investigation: Norman Baker

Given that the average human body contains ten pints of blood, and that about half of these must be lost before death ensues, we must also ask ourselves why there were clear signs at the postmortem-that Dr Kelly had retained much of his blood.

We cannot be sure exactly how much since, inexplicably, the pathologist’s report does not provide an estimate of the residual volume, but what he did record was the appearance of “livor mortis” on Dr Kelly’s body.

This purplish-red discolouration of the skin occurs when the heart is no longer pumping and blood begins to settle in the lower part of the body. But if Dr Kelly had bled to death, as we are led to believe, then significant livor mortis would not have occurred. Put simply, there would not have been enough blood in his body.

More significant still, while the effects of five pints of blood spurting from a body could not easily be hidden, the members of the search party who found his body did not even notice that Dr Kelly had apparently incised his wrist with a knife.

Their arrival was followed by that of paramedics who pointedly referred to the fact that there was remarkably little blood around the body.

If the idea that blood loss brought about Dr Kelly’s death is flawed, still less plausible is the suggestion that he chose an overdose to quicken his end.

Mai Pederson, a close friend of DrKelly’s, has confirmed that he hated all types of tablets and had an aversion even to swallowing a headache pill.

Yet we are told that he removed from his house three blister packs, each containing ten of the co-proxamol painkillers which his wife Janice took for her arthritis.

Each of these oval pills was about half an inch long. Since there was only one tablet left, the implication is that he had swallowed 29 of them. If this is right, we are being asked to believe that Dr Kelly indulged in a further masochistic act in an attempt to take his life.

A further objection is that police evidence states there was a halflitre bottle of Evian water by the body which had not been fully drunk.

Common sense tells us that quite a lot of water would be required to swallow 29 large tablets. It is frankly unlikely, with only a small bottle of water to hand, that any would have been left undrunk.

Stranger still, tests revealed the presence of only the equivalent of a fifth of one pill in Dr Kelly’s stomach.

Even allowing for natural metabolising, this cannot easily be reconciled with the idea that he swallowed 29 of them.

Forensic toxicologist Alexander Allan told the Hutton inquiry that although the levels of co-proxamol in Dr Kelly’s blood were higher than therapeutic levels, they were less than a third of what would normally be found in a fatal overdose.

Furthermore, it is generally accepted that concentrations of a drug in the blood can increase by as much as tenfold after death, leaving open the possibility that he consumed only a thirtieth of the dose necessary to kill him.

As for Dr Kelly’s state of mind, in the eyes of those who knew him well he was the last person who might be expected to take his own life.

A recent convert to the Baha’i faith which expressly forbids suicide, he was a strong character who had survived many difficult situations in the past.

Just a day before his 20th birthday in May 1964, his own mother had killed herself with an overdose. Though this had naturally affected him deeply at the time, there was nothing to suggest that it was on his mind at this point in his life.

His friend Mai Pederson recalled a conversation they once had about his mother’s death. Would he ever contemplate suicide himself, she asked. ‘Good God no, I couldn’t ever imagine doing that,” he is said to have replied. “I would never do it.”

Later many people would conclude that the seeds of his suicide lay in his uncomfortable appearance before MPs on the Foreign Affairs Committee on Tuesday, July 15, just three days before his death.

Grilled for more than an hour during this televised hearing, he was clearly under considerable pressure and yet one journalist recalled him smiling afterwards.

By the time he gave evidence before the Intelligence and Security Committee the following day, he was even managing to crack a joke or two.

His emotional state certainly did not appear to give any major cause for alarm on the morning of the Thursday he disappeared.

His wife Janice later described him as “tired, subdued but not depressed” and the e-mails he sent from his home during those hours suggested that his mood, if anything, was upbeat.

“Many thanks for your thoughts,” he wrote to one colleague. “It has been difficult. Hopefully will all blow over by the end of the week and I can travel to Baghdad and get on with the real work.”

Indeed, so keen was Dr Kelly to get back to Iraq that he spoke to Wing Commander John Clark at the Ministry of Defence about when he could return.

A trip was booked for him the following Friday and his diary, recovered by the police, shows that the trip had been entered for that day. People about to kill themselves do not generally first book an airline ticket for a flight they have no intention of taking.

Since none of this fits the profile of a man about to commit suicide, we are faced with an obvious question. If Dr Kelly did not kill himself, then who might have been responsible for his death?

There are, it must be admitted, a number of possible suspects. In the course of a long career in the shadowy world of arms control, Dr Kelly had made powerful enemies.

Back in 1991, for example, he was part of a team that exposed Russia’s tests of biological weapons for offensive purposes – a field in which they had invested huge sums of money. This could easily have sparked a desire for revenge, if not from the state itself then from individual Russians.

Dr Kelly also had intimate knowledge of biological weapons research in apartheid-era South Africa that some might have preferred not to see the light of day.

It has also been suggested that he had dealings with Mossad, the Israeli secret service, about illegal bacterial weapon activity.

But it seems very unlikely that the anger of old foes would have simmered for years and then exploded just as Dr Kelly emerged in the political spotlight in 2003.

Quite simply, it would qualify as an astonishing coincidence if the cause of his death were not rooted in the furore over Iraq.

At this point, it has to be asked whether there were elements in the British intelligence services, or indeed within 10 Downing Street itself, who would have wanted Dr Kelly dead.

This is a possibility I have seriously considered. But it is difficult, frankly, to think that anyone in the Government could have thought DrKelly’s death to be in their interest, even were they morally prepared to bring it about.

After all, the death of Dr Kelly presented Tony Blair with his greatest political challenge, and put the political focus firmly onto the whole Iraq debacle, which cannot be where the Government would have wanted it.

The more I investigated this affair, the more I realised that people who had worked with David Kelly suspected some kind of link with the Iraqis themselves.

Diplomat David Broucher told the Hutton inquiry that he interpreted Dr Kelly’s remark about being found “dead in the woods” to mean that “he was at risk of being attacked by the Iraqis in some way”.

Dr Kelly’s friend Mai Pederson confirmed to the police that the scientist had received death threats from supporters of Saddam Hussein, who regarded him as an enemy on account of his past success at uncovering their weapons programmes.

This was something Dr Kelly privately acknowledged but refused to be cowed by, in a very British, stiff upper lip kind of way.

The theory that he may have been murdered by elements loyal to Saddam is supported by Dick Spertzel, America’s most senior biological weapons inspector, who worked closely with Dr Kelly in Iraq.

“A number of us were on an Iraqi hit list,” he told me matter-of-factly. “I was number three, and David was a couple behind that.”

But Saddam loyalists are not the only Iraqis we need to consider. There are others, too, with rather closer links to the West.

Much of the information about Saddam’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, on which Britain and America based their case for war, was provided by Iraqi dissidents eager to see his overthrow.

This information was sensational and, as events turned out, wildly distorted and in most regards plain false.

One of the central figures here was Ahmed Chalabi, leader of the so-called Iraqi National Congress and the CIA’s favourite Iraqi opposition politician.

A financier with a decidedly chequered past – he was found guilty of embezzlement and forgery after $158 million disappeared from a bank he founded in Jordan – Chalabi made no secret of his wish to drag the United States into war with Saddam and was apparently prepared to say anything to achieve that end.

A key Iraqi informer codenamed “Curveball” – who claimed to have led a team equipping mobile laboratories to produce biological weapons for Saddam, but was later entirely discredited – is believed to have been the brother of one of Chalabi’s aides.

Chalabi’s fingerprints can also be found on the now notorious claims by another defector that Saddam had 20 or more secret sites where weapons of mass destruction could be found. Subsequent searches showed this allegation to be utterly without foundation.

Alastair Campbell: ‘Unprecedented and vitriolic attack on the BBC’

Naturally, those like Dr Kelly who, by sticking to the facts, weakened the case for invasion beforehand and discredited those who had exaggerated it afterwards, were unhelpful to Chalabi and his colleagues. The last thing they wanted was the sober truth to prevail.

Another important figure here is Iyad Allawi, leader of the Iraqi National Accord, another organisation created to oppose Saddam. Before they parted ways, he was Saddam’s supporter and friend.

There are many who tell of Allawi’s violent history. As a young man, he is alleged to have been present at the torture of Iraqi communists who were hung from the ceiling and beaten.

While living in London in the Seventies, he was allegedly the head of Iraq’s intelligence operation in Europe, informing on opponents of Saddam who will have faced torture and death when they returned home.

Allawi went on to develop a fruitful relationship with MI6 and the CIA. After the Iraq invasion, he was appointed Prime Minister in the country’s interim government – only to face allegations (which he strongly denied) that he had personally shot seven insurgents in the head with a pistol at Baghdad’s Al-Amariyah security centre.

“This is how we must deal with terrorists,” Allawi is alleged to have told a stunned audience of close to 30 onlookers. “We must destroy anyone who wants to destroy the Iraqi people.”

The new Prime Minister’s actions are said to have prompted one U.S. official to comment: “What a mess we’re in – we got rid of one son of a bitch only to get another.”

The Americans apparently referred to Allawi as “Saddam lite”.

Before the Iraq invasion, Allawi’s organisation – just like Ahmed Chalabi’s – was responsible for eye- catching but groundless intelligence exploited by supporters of war. #

In the case of Allawi’s group, it was reports passed to MI6 in the spring and summer of 2002, including the false claim that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction which he could deploy at 45 minutes’ notice.

This now infamous “45-minute claim” fed through to the dossier of intelligence which was used as the justification for our involvement in the invasion of Iraq.

It was this dossier, and the 45-minute claim in particular, that David Kelly challenged in his crucial interview with the BBC.

By doing so, did he sign his own death warrant?

t was a normal day in Westminster. The House was sitting and Parliament was full of the usual collection of weary MPs like me traipsing from one meeting to the next, and primly dressed men in ceremonial tights harrumphing around the place.

I left my office and took the stairs down to the reception area where my next appointment was waiting for me.

I had never heard of him before and my mind was on the pile of unfinished work on my desk rather than the meeting about to take place.

I assumed it would be a short and uneventful one, but I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Happier times: Dr Kelly was known as a devoted husband and father

My visitor was nervous and distracted. I began to wonder if he was unwell. Then he suddenly decided to open up.

The ostensible reason given for the meeting was essentially a pretext. My visitor really wanted to talk about the death of David Kelly.

Let me say here that I subsequently checked out this person’s bona fides and was able to confirm them. He was who he said he was, and worked where he said he worked.

I have to be very careful with what I say about him, as he clearly believes that he is at risk if he is identified as producing information. For this reason, I can also relate only a fraction of what he said to me, and what is recorded in my extensive contemporaneous notes.

He told me of a meeting where members of a UK-based Iraqi circle had named people who claimed involvement in Dr Kelly’s death.

It seems the Iraqis felt Dr Kelly had besmirched them through his publicly reported actions in doubting the intelligence their organisation had provided to MI6, not least in respect to the now infamous September dossier.

There was also concern that, had he lived, Dr Kelly might have gone public with even more details.

I stayed in contact with my informant, by necessarily elaborate means, and one day he undertook to send me some specific material. It never arrived, and he went quiet.

Some weeks later, I discovered why. When we met again, he was even jumpier than at our first meeting and what he told me was chilling.

On the day after he had undertaken to post me the material we had discussed, he kept an appointment, made at short notice. He had been promised certain information, which was to be conveyed to him by a contact.

I learnt that at that impromptu meeting he was subjected to an horrific attack by an unknown assailant, the full details of which he has asked me not to reveal. Perhaps not surprisingly, he has been reluctant to get any further involved, though he remains well.

The information he had given me had pushed my investigation on immeasurably. It now seemed that I was closer than ever to understanding who had killed Dr Kelly but one thing remained unexplained. Why would his death have been made to look like suicide?

I realised that a clue to this might lie in another piece of information given to me by my visitor at Westminster before he decided, for his own safety, that he could help me no longer.

He told me that the police or the security services had got wind of a possible plan to assassinate Dr Kelly but were too late to prevent his murder taking place.

Suppose this were true – and suppose also that they were told that, in the interests of Queen and country, this information should not come out for fear of destabilising both Britain and Iraq.

Under those circumstances might it just be possible that they saw it as their patriotic duty to intervene – allowing the impression to be formed that Dr Kelly had killed himself?

It seemed incredible but the more I thought about it, the more I realised it might explain some strange anomalies in the police’s handling of Dr Kelly’s case.

The first relates to a secret file of evidence submitted to the Hutton inquiry by Thames Valley Police.

While the contents remain classified, the cover is publicly available and reveals that the codename for the investigation was Operation Mason.

This has given rise to wild rumours of a freemasonry angle to the case but, while these are almost certainly without foundation, what is more concerning is that the start time of Operation Mason is given as 2.30pm on Thursday July 17, which was half an hour before Dr Kelly set off from his home for a walk from which he would never return.

Grief-stricken: Mourners at Dr Kelly’s funeral

When I challenged this curious timing, I was told that the starttime of an operation is fixed not to relate to the moment that the police know of an incident but to reflect the period of interest to them. This sounds superficially plausible until one reflects that any police investigation worthy of the name would look back way before 2.30 on that Thursday afternoon.

Yet what is the explanation, if this is not the case? Premonition and occult powers can be safely discounted, which leaves us with the possibility that some element within Thames Valley Police had foreknowledge, to at least some degree, of that afternoon’s tragic events.

This might help us understand other curiosities about the case – including two searches made of the Kelly home in the early hours of the morning after Dr Kelly vanished.

The first, conducted shortly after midnight when officers first arrived at the house, made some sense. Dr Kelly might, for example, have suffered a heart attack in a little-used part of the house – but a second more detailed search at around 5am is more difficult to understand.

Surely if Dr Kelly had been there, he would have been found the first time. More puzzling still, Mrs Kelly was asked to wait in the garden while a dog was put through the house.

A chief constable with whom I have discussed this matter was unable to explain why Mrs Kelly would have been asked to leave her home.

In his view, if the objective was to locate Dr Kelly, her knowledge of the house’s layout would have been helpful in any search.

He described the police actions as “bizarre” but, as we shall see, they become entirely understandable if there was a hitherto undisclosed reason for this second search.

Could it be linked, for example, to a number of strange inconsistencies in the testimony of those who saw Dr Kelly’s body on the morning it was discovered?

Two key pieces of evidence suggesting that Dr Kelly had taken his life were the presence at the scene of the blunt pruning knife with which he was supposed to have cut his wrist, and the halfdrunk bottle of water which, we are led to believe, he used to help him swallow his wife’s painkillers.

Strangely, however, no mention was made of these items by Louise Holmes and Paul Chapman, two volunteers who had joined the search party that morning and came across Dr Kelly’s body at about 8.30am.

They must have been truly unobservant to miss the bloodied knife and water bottle.

Yet this was not the only apparent difference between what they saw and the accounts given by others. For example, Paul Chapman told the Hutton inquiry that Dr Kelly’s body was sitting on the ground and leaning up against a tree, a view with which Ms Holmes concurred.

But those who came later said that Dr Kelly was lying on his back with the knife and water bottle next to him.

The position of the water bottle was interesting: propped up, at a slight angle, to the left of Dr Kelly’s head, with the cap by the side of it.

Given that Dr Kelly was righthanded, the police might have been expected to find it on that side of his body, but the configuration is just about possible if DrKelly were sitting up against the tree.

If, however, he was lying on his back, we are asked to believe that he placed the water bottle, presumably with his undamaged and natural right hand, by his head on the left and placed the cap neatly next to it.

Despite his serious injuries, he even managed, at this contortionist’s angle, to ensure that the bottle was propped up.

It’s also strange that no mention was made at the Hutton inquiry of whether there were any fingerprints on the knife. No- one volunteered any information on this and no one was asked.

After some delay, Thames Valley Police finally told me earlier this year that no fingerprints were recovered from the knife. And yet we know from the evidence of forensic biologist Roy Green that the knife was blood-marked.

Try holding a knife tightly, as if you were about to use it to make an incision. Is it not a natural action to use your fingers to apply pressure on the knife to hold it firm and in place?

Did Dr Kelly then have a most curious way of holding a knife? Or are we being asked to believe that he tidily wiped his prints off, just as he tidily put the bottle cap next to the water bottle by his left shoulder, and the empty coproxamol blister packs tidily back in his coat pocket?

Other confusion arose over what he was wearing when he left home. Many of the papers published in the weekend immediately following his death suggested that he had been jacketless – a view supported by Acting Superintendent David Parnell of Thames Valley Police, who was quoted as saying he was “dressed in jeans and a cotton shirt”.

By contrast, the Hutton inquiry was told that he was wearing a coat when he was found – variously described as a green or blue Barbour-type wax jacket.

Given that it was a warmish day in July, albeit somewhat cloudy, it’s perhaps questionable whether he would have donned a wax Barbour, but, if the theory that he committed suicide is correct, it’s conceivable that he would have needed the pockets to transport his knife, water bottle and tablets.

If, on the other hand, he was murdered, then perhaps not just the coat, but the knife, the pills and the water bottle were all taken from the Kelly home to Harrowdown Hill by someone other than Dr Kelly with the express purpose of creating a suicide scene.

Someone wanting to kill themselves might have been expected to use a sharp blade – a razor blade, for instance – rather than a blunt pruning knife.

But then, the knife was one that Dr Kelly had owned since boyhood, making it a very convenient clue to support a suicide verdict, just like the painkillers that could be traced back to others at his home.

It is all too easy to dismiss so-called “conspiracy theories”. But history shows us that conspiracies do happen – and that suicides can be staged to cover murderers’ tracks.

All the evidence leads me to believe that this is what happened in the case of Dr Kelly. In Monday’s Mail, I’ll describe how I believe his killing was carried out.

EXTRACTED from The Strange Death Of David Kelly by Norman Baker, published by Methuen on November 12 at £9.99. ° Norman Baker 2007. To order a copy (p&p free), call 0845 606 4206.

NORMAN BAKER is the Lib-Dem spokesman for Cabinet Office Affairs who brought down Peter Mandelson over the Hinduja passport affair and blocked attempts to hush up MPs’ expenses.

Related Global Research Articles on the Death of David Kelly

Iraq whistleblower Dr Kelly was murdered to silence him, says MP – 2007-10-20

No Inquest into the Death of Dr. David Kelly – by Dr. C. Stephen Frost – 2007-07-15

Mysterious Death of Dr. David Kelly: Murder theory that just won’t go away – 2007-04-14

VIDEO Dr David Kelly – Conspiracy – by BBC – 2007-02-28

VIDEO WEBCAST: The Death of Dr. David Kelly – by BBC – 2007-02-25

One in four doubt David Kelly killed himself – 2007-02-16

BBC reopens Kelly case with new film – by Maurice Chittenden – 2006-11-19

The Hutton Inquiry And The Murder Of Dr. David Kelly – by Ken Welch – 2006-11-07

The David Kelly “Dead in the Woods” PSYOP – by Rowena Thursby – 2006-10-20

Uncovering the Truth about the Death of David Kelly – by Rowena Thursby – 2006-09-17

The Mysterious Death of David Kelly – by Rowena Thursby – 2006-08-17

David Kelly Death – paramedics query verdict – by Antony Barnett – 2005-06-17