The Weaponization of “Disinformation” Pseudo-experts and Bureaucrats: How the Federal Government Partnered with Universities to Censor Americans’ Political Speech

Report of the Committee of the Judiciary and Select Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Executive Summary

Following the 2016 presidential election, a sensationalized narrative emerged that foreign “disinformation” affected the integrity of the election. These claims, fueled by left-wing election denialism about the legitimacy of President Trump’s victory, sparked a new focus on the role of social media platforms in spreading such information.[1] “Disinformation” think tanks and “experts,” government task forces, and university centers were formed, all to study and combat the alleged rise in alleged mis- and disinformation. As the House Committee on the Judiciary and the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government have shown previously, these efforts to combat so-called foreign influence and misinformation quickly mutated to include domestic—that is, American—speech.[2]

The First Amendment to the Constitution rightly limits the government’s role in monitoring and censoring Americans’ speech, but these disinformation researchers (often funded, at least in part, by taxpayer dollars) were not strictly bound by these constitutional guardrails. What the federal government could not do directly, it effectively outsourced to the newly emerging censorship-industrial complex.

Enter the Election Integrity Partnership (EIP), a consortium of “disinformation” academics led by Stanford University’s Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) that worked directly with the Department of Homeland Security and the Global Engagement Center, a multi-agency entity housed within the State Department, to monitor and censor Americans’ online speech in advance of the 2020 presidential election. Created in the summer of 2020 “at the request” of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA),[3] the EIP provided a way for the federal government to launder its censorship activities in hopes of bypassing both the First Amendment and public scrutiny.

In the lead-up to the 2020 election, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the American public and lawmakers debated the merits of unprecedented, mid-election-cycle changes to election procedures.[4] These issues, like all contemporary discourse about questions of political import, were extensively discussed on the world’s largest social media platforms—the modern town square. But as American citizens, including candidates in these elections, attempted to exercise their First Amendment rights on these platforms, their constitutionally protected speech was intentionally suppressed as a consequence of the federal government’s direct coordination with third-party organizations, particularly universities, and social media platforms.[5] Speech concerning elections—the process by which Americans select their representatives—is of course entitled to robust First Amendment protections.[6] This bedrock principle is even more critical as it relates to speech by political candidates.[7] But as disinformation “experts” acknowledge, the labeling of any kind of speech is “inherently political”[8] and itself a form of “censorship.”[9]

This interim staff report details the federal government’s heavy-handed involvement in the creation and operation of the EIP, which facilitated the censorship of Americans’ political speech in the weeks and months leading up to the 2020 election. This report also publicly reveals for the first time secret “misinformation” reports from the EIP’s centralized reporting system, previously accessible only to select parties, including federal agencies, universities, and Big Tech. The Committee and Select Subcommittee obtained these nonpublic reports from Stanford University only under the threat of contempt of Congress. These reports of alleged mis- and disinformation were used to censor Americans engaged in core political speech in the lead up to the 2020 election.

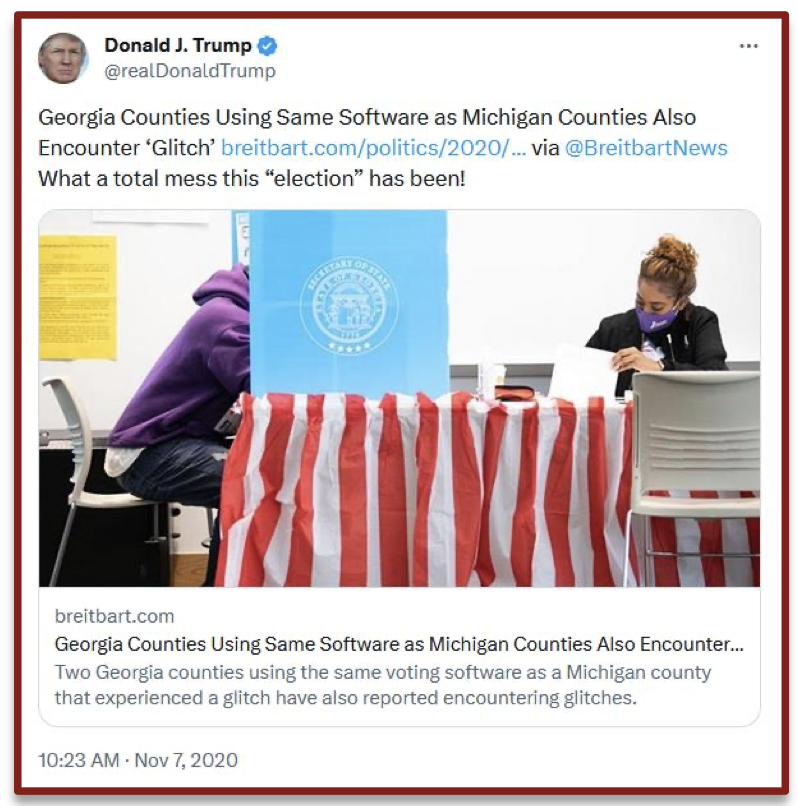

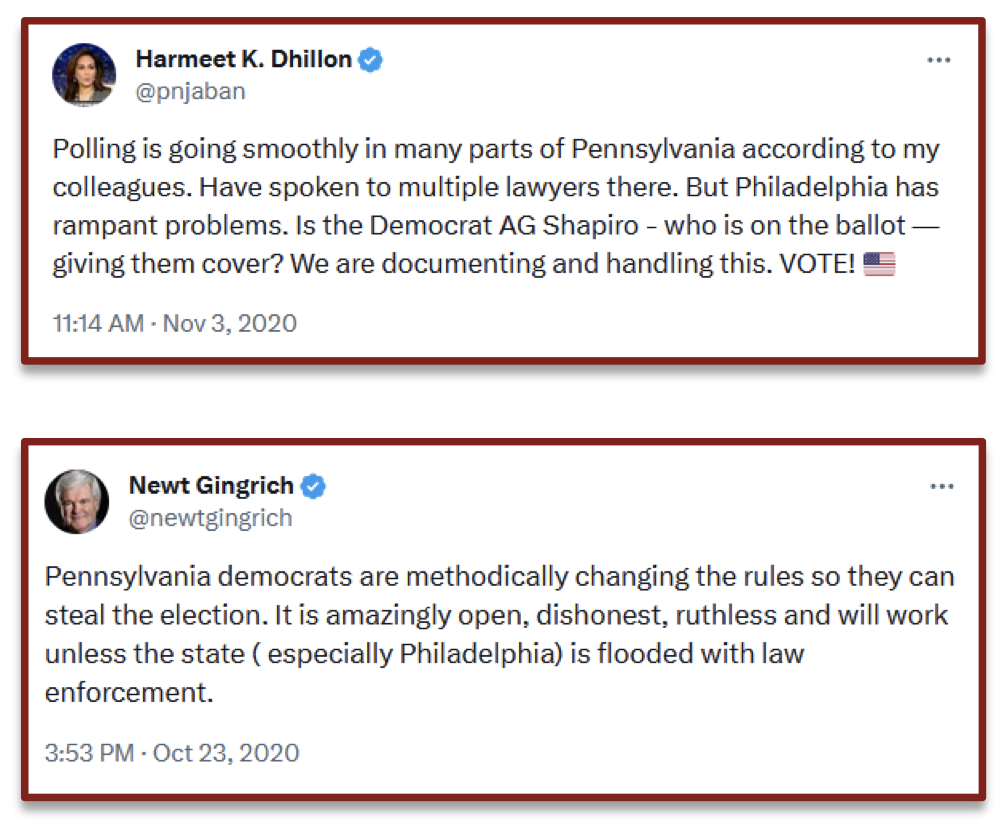

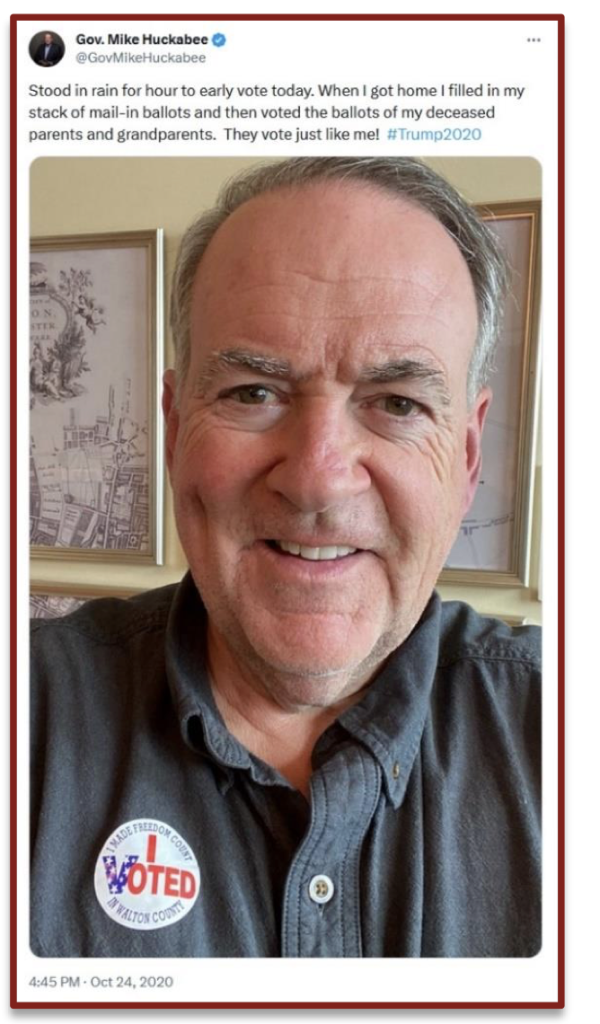

As this new information reveals, and this report outlines, the federal government and universities pressured social media companies to censor true information, jokes, and political opinions. This pressure was largely directed in a way that benefitted one side of the political aisle: true information posted by Republicans and conservatives was labeled as “misinformation” while false information posted by Democrats and liberals was largely unreported and untouched by the censors. The pseudoscience of disinformation is now—and has always been—nothing more than a political ruse most frequently targeted at communities and individuals holding views contrary to the prevailing narratives.

The EIP’s operation was straightforward: “external stakeholders,” including federal agencies and organizations funded by the federal government, submitted misinformation reports directly to the EIP. The EIP’s misinformation “analysts” next scoured the internet for additional examples for censorship. If the submitted report flagged a Facebook post, for example, the EIP analysts searched for similar content on Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, Reddit, and other major social media platforms. Once all of the offending links were compiled, the EIP sent the most significant ones directly to Big Tech with specific recommendations on how the social media platforms should censor the posts, such as reducing the posts’ “discoverability,” “suspending [an account’s] ability to continue tweeting for 12 hours,” “monitoring if any of the tagged influencer accounts retweet” a particular user, and, of course, removing thousands of Americans’ posts.[10]

Who was being censored?

- President Donald J. Trump

- Senator Thom Tillis

- Speaker Newt Gingrich

- Governor Mike Huckabee

- Congressman Thomas Massie

- Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene

- Newsmax

- The Babylon Bee

- Sean Hannity

- Mollie Hemingway

- Harmeet Dhillon

- Charlie Kirk

- Candace Owens

- Jack Posobiec

- Tom Fitton

- James O’Keefe

- Benny Johnson

- Michelle Malkin

- Sean Davis

- Dave Rubin

- Paul Sperry

- Tracy Beanz

- Chanel Rion

- An untold number of everyday Americans of all political affiliations

What was being censored?

- True information

- Jokes and satire

- Political opinions

As part of this report, the Committee and Select Subcommittee are releasing all of the previously secret, archived data the Committee has obtained pursuant to a subpoena issued to Stanford University, which Stanford produced only after the threat of contempt.[11] In the lead-up to the 2020 election, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had the ability to see what American speech was being censored. Today, as a result of the Committee’s and SelectSubcommittee’s investigation, political candidates, journalists, and all Americans have the opportunity to see if they were targeted by their government and what viewpoints DHS, Stanford, and others worked to censor. While the EIP disproportionately targeted conservatives, Americans of all political affiliations were victims of censorship.

The First Amendment prohibits the government from “abridging the freedom of speech” and protects “the right of the people . . . to petition the Government.”[12] The ability of Americans to criticize the government and its policies is a fundamental and sacrosanct principle of our constitutional republic. The Supreme Court has long recognized that for “core political speech” “the importance of First Amendment protections is at its zenith.”[13] Moreover, as constitutional scholars have explained: “Because the First Amendment bars ‘abridging’ the freedom of speech, any law or government policy that reduces that freedom on the [social media] platforms . . . violates the First Amendment.”[14]

The government may not dictate the type or terms of the criticism to which it is subject, even when—especially when—the government disagrees with the merits of that criticism. To inform potential legislation, the Committee and the Select Subcommittee have been investigating the Executive Branch’s collusion with third-party intermediaries, including universities, to censor protected speech on social media.

The Committee and the Select Subcommittee are responsible for investigating “violation[s] of the civil liberties of citizens of the United States.”[15] In accordance with this mandate, this interim staff report on CISA’s violations of the First Amendment and other unconstitutional activities fulfills the obligation to identify and report on the weaponization of the federal government against American citizens. The Committee’s and Select Subcommittee’s investigation remains ongoing. CISA still has not adequately complied with a subpoena for relevant documents, and more fact-finding is necessary. In order to better inform the Committee’s legislative efforts, the Committee and Select Subcommittee will continue to investigate how the Executive Branch worked with social media platforms and other intermediaries to censor disfavored viewpoints in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Tim Starks, Russian trolls on Twitter had little influence on 2016 voters, WASH. POST (Jan. 9, 2023) (“The study, which the New York University Center for Social Media and Politics helmed, explores the limits of what Russian disinformation and misinformation was able to achieve on one major social media platform in the 2016 elections.”); id. (“There was no measurable impact on ‘political attitudes, polarization, and vote preferences and behavior’ from the Russian accounts and posts.”).

2 See STAFF OF SELECT SUBCOMM. ON THE WEAPONIZATION OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF THE H. COMM. ON THE JUDICIARY, 118TH CONG., THE WEAPONIZATION OF CISA: HOW A “CYBERSECURITY” AGENCY COLLUDED WITH BIG TECH AND “DISINFORMATION” PARTNERS TO CENSOR AMERICANS (Comm. Print June 26, 2023).

3 Email from Graham Brookie to Atlantic Council employees (July 31, 2020, 5:54 PM) (on file with the Comm.).

4 See, e.g., REPUBLICAN STAFF OF THE H. COMM. ON THE JUDICIARY AND THE COMM. ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM, 116TH CONG., HOW DEMOCRATS ARE ATTEMPTING TO SOW UNCERTAINTY, INACCURACY, AND DELAY IN THE 2020 ELECTION (Sept. 23, 2020); see also Changes to election dates, procedures, and administration in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, 2020, BALLOTPEDIA (last visited Nov. 3, 2023).

5 See Missouri v. Biden, No. 23-30445, (5th Cir. Oct. 3, 2023), ECF No. 268-1 (affirming preliminary injunction in part); Missouri v. Biden, No. 3:22-cv-01213 (W.D. La. Jul. 4, 2023), ECF No. 293 (memorandum ruling granting preliminary injunction).

6 See, e.g., Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 452 (2011) (“[S]peech on public issues occupies the highest rung of the hierarchy of First Amendment values”) (quoting Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138, 145 (1983)); Ariz. Free Enter. Club’s Freedom Club PAC v. Bennett, 564 U.S. 721, 755 (2011) (internal quotation marks and citation omitted) (The First Amendment protects the “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.”); see also McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Comm’n, 514 U.S. 334, 346 (1995) (cleaned up) (“There is practically universal agreement that a major purpose of the Amendment was to protect the free discussion of governmental affairs, of course including discussions of candidates.”).

7 “The First Amendment ‘has its fullest and most urgent application precisely to the conduct of campaigns for political office,’” FEC v. Cruz, 142 S. Ct. 1638, 1650 (2022) (quoting Monitor Patriot Co. v. Roy, 401 U.S. 265, 272 (1971)); see also Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 52 (1976) (A candidate “has a First Amendment right to engage in the discussion of public issues and vigorously and tirelessly to advocate his own election.”).

8 Email from Suzanne Spaulding (Google Docs) to Kate Starbird (May 16, 2022, 6:27 PM) (on file with the Comm.); see also Kate Starbird et al., Proposal to the National Science Foundation for “Collaborative Research: SaTC: Core: Large: Building Rapid-Response Frameworks to Support Multi-Stakeholder Collaborations for Mitigating Online Disinformation” (Jan. 29, 2021) (unpublished proposal) (on file with the Comm.) (“The study of disinformation today invariably includes elements of politics.”).

9 Team F-469 First Pitch to NSF Convergence Accelerator, UNIV. OF MICH., at 1 (presentation notes) (Oct. 27, 2021) (on file with the Comm.).

10 See, e.g., EIP-581, submitted by [REDACTED], ticket created (Nov. 2, 2020, 2:36 PM) (archived Jira ticket data produced to the Comm.); EIP-673, submitted by [REDACTED], ticket created (Nov. 3, 2020, 11:51 AM) (archived Jira ticket data produced to the Comm.) (citing Mike Coudrey, TWITTER (Nov. 3, 2020, 10:13 AM), https://twitter.com/MichaelCoudrey/status/1323644406998597633); EIP-638, submitted by [REDACTED], ticket created (Nov. 3, 2020, 9:23 AM) (archived Jira ticket data produced to the Comm.).

11 See App’x II.

12 U.S. Const. amend. I.

13 Meyer v. Grant, 486 U.S. 414, 420, 425 (1988) (internal quotation marks omitted).

14 Philip Hamburger, How the Government Justifies Its Social-Media Censorship, WALL ST. J. (June 9, 2023).

15 H. Res. 12 § 1(b)(E).

Featured image: A US government propaganda poster from the 1940s (Source: Multipolarista)