War Profiteering and the Concentration of Income and Wealth in America

Escalating Military Spending

How Escalation of War and Military Spending Are Used as Disguised or Roundabout Ways to Reverse the New Deal and Redistribute National Resources in Favor of the Wealthy.

Escalating Military Spending: Income Redistribution in Disguise

Critics of the recent U.S. wars of choice have long argued that they are all about oil. “No Blood for Oil” has been a rallying cry for most of the opponents of the war.

It can be demonstrated, however, that there is another (less obvious but perhaps more critical) factor behind the recent rise of U.S. military aggressions abroad: war profiteering by Pentagon contractors.

Frequently invoking dubious “threats to our national security and/or interests,” these beneficiaries of war dividends, the military–industrial complex and related businesses whose interests are vested in the Pentagon’s appropriation of public money, have successfully used war and military spending to justify their lion’s share of tax dollars and to disguise their strategy of redistributing national income in their favor.

This cynical strategy of disguised redistribution of national resources from the bottom to the top is carried out by a combination of (a) drastic hikes in the Pentagon budget, and (b) equally drastic tax cuts for the wealthy. As this combination creates large budget deficits, it then forces cuts in non-military public spending as a way to fill the gaps that are thus created. As a result, the rich are growing considerably richer at the expense of middle– and low–income classes.

Despite its critical importance, most opponents of war seem to have given short shrift to the crucial role of the Pentagon budget and its contractors as major sources of war and militarism—a phenomenon that the late President Eisenhower warned against nearly half a century ago. Perhaps a major reason for this oversight is that critics of war and militarism tend to view the U.S. military force as primarily a means for imperialist gains—oil or otherwise.

The fact is, however, that as the U.S. military establishment has grown in size, it has also evolved in quality and character: it is no longer simply a means but, perhaps more importantly, an end in itself—an imperial force in its own right. Accordingly, the rising militarization of U.S. foreign policy in recent years is driven not so much by some general/abstract national interests as it is by the powerful special interests that are vested in the military capital, that is, war industries and war–related businesses.

The Magnitude of U.S. Military Spending

Even without the costs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which are fast surpassing half a trillion dollars, U.S. military spending is now the largest item in the federal budget. Officially, it is the second highest item after Social Security payments. But Social Security is a self-financing trust fund. So, in reality, military spending is the highest budget item.

The Pentagon budget for the current fiscal year (2007) is about $456 billion. President Bush’s proposed increase of 10% for next year will raise this figure to over half a trillion dollars, that is, $501.6 billion for fiscal year 2008.

A proposed supplemental appropriation to pay for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq “brings proposed military spending for FY 2008 to $647.2 billion, the highest level of military spending since the end of World War II—higher than Vietnam, higher than Korea, higher than the peak of the Reagan buildup.”[1]

Using official budget figures, William D. Hartung, Senior Fellow at the World Policy Institute in New York, provides a number of helpful comparisons:

- Proposed U.S. military spending for FY 2008 is larger than military spending by all of the other nations in the world combined.

- At $141.7 billion, this year’s proposed spending on the Iraq war is larger than the military budgets of China and Russia combined. Total U.S. military spending for FY2008 is roughly ten times the military budget of the second largest military spending country in the world, China.

- Proposed U.S. military spending is larger than the combined gross domestic products (GDP) of all 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

- The FY 2008 military budget proposal is more than 30 times higher than all spending on State Department operations and non-military foreign aid combined.

- The FY 2008 military budget is over 120 times higher than the roughly $5 billion per year the U.S. government spends on combating global warming.

- The FY 2008 military spending represents 58 cents out of every dollar spent by the U.S. government on discretionary programs: education, health, housing assistance, international affairs, natural resources and environment, justice, veterans’ benefits, science and space, transportation, training/employment and social services, economic development, and several more items.[2]

Although the official military budget already eats up the lion’s share of public money (crowding out vital domestic needs), it nonetheless grossly understates the true magnitude of military spending. The real national defense budget, according to Robert Higgs of the Independent Institute, is nearly twice as much as the official budget. The reason for this understatement is that the official Department of Defense budget excludes not only the cost of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also a number of other major cost items.[3]

These disguised cost items include budgets for the Coast Guard and the Department of Homeland Security; nuclear weapons research and development, testing, and storage (placed in the Energy budget); veterans programs (in the Veteran’s Administration budget); most military retiree payments (in the Treasury budget); foreign military aid in the form of weapons grants for allies (in the State Department budget); interest payments on money borrowed to fund military programs in past years (in the Treasury budget); sales and property taxes at military bases (in local government budgets); and the hidden expenses of tax-free food, housing, and combat pay allowances.

After adding these camouflaged and misplaced expenses to the official Department of Defense budget, Higgs concludes: “I propose that in considering future defense budgetary costs, a well-founded rule of thumb is to take the Pentagon’s (always well publicized) basic budget total and double it. You may overstate the truth, but if so, you’ll not do so by much.”[4]

Escalation of the Pentagon Budget and the Rising Fortunes of Its Contractors

The Bush administration’s escalation of war and military spending has been a boon for Pentagon contractors. That the fortunes of Pentagon contractors should rise in tandem with the rise of military spending is not surprising. What is surprising, however, is the fact that these profiteers of war and militarism have also played a critical role in creating the necessary conditions for war profiteering, that is, in instigating the escalation of the recent wars of choice and the concomitant boom of military spending.[5]

Giant arms manufacturers such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman have been the main beneficiaries of the Pentagon’s spending bonanza. This is clearly reflected in the continuing rise of the value of their shares in the stock market:

“Shares of U.S. defense companies, which have nearly trebled since the beginning of the occupation of Iraq, show no signs of slowing down. . . . The feeling that makers of ships, planes and weapons are just getting into their stride has driven shares of leading Pentagon contractors Lockheed Martin Corp., Northrop Grumman Corp., and General Dynamics Corp. to all-time highs.”[6]

Like its manufacturing contractors, the Pentagon’s fast-growing service contractors have equally been making fortunes by virtue of its tendency to shower private contractors with tax-payers’ money. These services are not limited to the relatively simple or routine tasks and responsibilities such food and sanitation services. More importantly, they include “contracts for services that are highly sophisticated [and] strategic in nature,” such as the contracting of security services to corporate private armies, or modern day mercenaries. The rapid growth of the Pentagon’s service contracting is reflected (among other indicators) in these statistics: “In 1984, almost two-thirds of the contracting budget went for products rather than services. . . . By fiscal year 2003, 56 percent of Defense Department contracts paid for services rather than goods.”[7]

The spoils of war and the devastation in Iraq have been so attractive that an extremely large number of war profiteers have set up shop in that country in order to participate in the booty: “There are about 100,000 government contractors operating in Iraq, not counting subcontractors, a total that is approaching the size of the U.S. military force there, according to the military’s first census of the growing population of civilians operating in the battlefield,” reported The Washington Post in its 5 December 2006 issue.

The rise in the Pentagon contracting is, of course, a reflection of an overall policy and philosophy of outsourcing and privatizing that has become fashionable ever since President Reagan arrived in the White House in 1980. Reporting on some of the effects of this policy, Scott Shane and Ron Nixon of the New York Times recently wrote: “Without a public debate or formal policy decision, contractors have become a virtual fourth branch of government. On the rise for decades, spending on federal contracts has soared during the Bush administration, to about $400 billion last year from $207 billion in 2000, fueled by the war in Iraq, domestic security and Hurricane Katrina, but also by a philosophy that encourages outsourcing almost everything government does.”[8]

Redistributive Militarism: Escalation of Military Spending Redistributes Income from Bottom to Top

But while the Pentagon contractors and other beneficiaries of war dividends are showered with public money, low- and middle-income Americans are squeezed out of economic or subsistence resources in order to make up for the resulting budgetary shortfalls. For example, as the official Pentagon budget for 2008 fiscal year is projected to rise by more than 10 percent, or nearly $50 billion, “a total of 141 government programs will be eliminated or sharply reduced” to pay for the increase. These would include cuts in housing assistance for low-income seniors by 25 percent, home heating/energy assistance to low-income people by 18 percent, funding for community development grants by 12.7 percent, and grants for education and employment training by 8 percent.[9]

Combined with redistributive militarism and generous tax cuts for the wealthy, these cuts have further exacerbated the ominously growing income inequality that started under President Reagan. Ever since Reagan arrived in the White House in 1980, opponents of non-military public spending have been using an insidious strategy to cut social spending, to reverse the New Deal and other social safety net programs, and to redistribute national/public resources in favor of the wealthy. That cynical strategy consists of a combination of drastic increases in military spending coupled with equally drastic tax cuts for the wealthy. As this combination creates large budget deficits, it then forces cuts in non-military public spending (along with borrowing) to fill the gaps thus created.

For example, at the same time that President Bush is planning to raise military spending by $50 billion for the next fiscal year, he is also proposing to make his affluent-targeted tax cuts permanent at a cost of $1.6 trillion over 10 years, or an average yearly cut of $160 billion. Simultaneously, “funding for domestic discretionary programs would be cut a total of $114 billion” in order to pay for these handouts to the rich. The targeted discretionary programs to be cut include over 140 programs that provide support for the basic needs of low- and middle-income families such as elementary and secondary education, job training, environmental protection, veterans’ health care, medical research, Meals on Wheels, child care and HeadStart, low-income home energy assistance, and many more.[10]

According to the Urban Institute–Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, “if the President’s tax cuts are made permanent, households in the top 1 percent of the population (currently those with incomes over $400,000) will receive tax cuts averaging $67,000 a year by 2012. . . . The tax cuts for those with incomes of over $1 million a year would average $162,000 a year by 2012.”[11]

Official macroeconomic figures show that, over the past five decades or so, government spending (at the federal, state and local levels) as a percentage of gross national product (GNP) has remained fairly steady—at about 20 percent. Given this nearly constant share of the public sector of national output/income, it is not surprising that increases in military spending have almost always been accompanied or followed by compensating decreases in non-military public spending, and vice versa.

For example, when by virtue of FDR’s New Deal reforms and LBJ’s metaphorical War on Poverty, the share of non-military government spending rose significantly the share of military spending declined accordingly. From the mid 1950s to the mid 1970s, the share of non-military government spending of GNP rose from 9.2 to 14.3 percent, an increase of 5.1 percent. During that time period, the share of military spending of GNP declined from 10.1 to 5.8 percent, a decline of 4.3 percent.[12]

That trend was reversed when President Reagan took office in 1980. In the early 1980s, as President Reagan drastically increased military spending, he also just as drastically lowered tax rates on higher incomes. The resulting large budget deficits were then paid for by more than a decade of steady cuts on non-military spending.

Likewise, the administration of President George W. Bush has been pursuing a similarly sinister fiscal policy of cutting non-military public spending in order to pay for the skyrocketing military spending and the generous tax cuts for the affluent.

Interestingly (though not surprisingly), changes in income inequality have mirrored changes in government spending priorities, as reflected in the fiscal policies of different administrations. Thus, when the share of non-military public spending rose relative to that of military spending from the mid 1950 to the mid 1970s, and the taxation system or policy remained relatively more progressive compared to what it is today, income inequality declined accordingly.

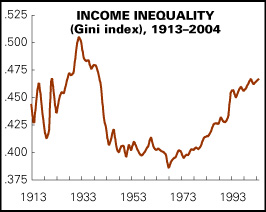

But as President Reagan reversed that fiscal policy by raising the share of military spending relative to non-military public spending and cutting taxes for the wealthy, income inequality also rose considerably. As Reagan’s twin policies of drastic increases in military spending and equally sweeping tax cuts for the rich were somewhat tempered in the 1990s, growth in income inequality slowed down accordingly. In the 2000s, however, the ominous trends that were left off by President Reagan have been picked up by President George W. Bush: increasing military spending, decreasing taxes for the rich, and (thereby) exacerbating income inequality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Income Inequality in the U.S. (Gini Index), 1913-2004

Source: Doug Henwood, Left Business Observer, No. 114 (December 2006), p. 1

Leaving small, short-term fluctuations aside, Figure 1 shows two major peaks and a trough of the long-term picture of income inequality in the United States. The first peak was reached during the turbulent years of the Great Depression (1929–1933). But it soon began to decline with the implementation of the New Deal reforms in the mid 1930s. The ensuing decline continued almost unabated until 1968, at which time we note the lowest level of inequality.

After 1968, the improving trend in inequality changed course. But the reversal was not very perceptible until the early 1980s, after which time it began to accelerate—by virtue (or vice) of Reaganomics. Although the deterioration that was thus set in motion by the rise of neoliberalism and supply-side economics somewhat slowed down in the 1990s, it has once again gathered steam under President George W. Bush, and is fast approaching the peak of the Great Depression.

It is worth noting that even at its lowest level of 1968, income inequality was still quite lopsided: the richest 20 percent of households made as much as ten times more than the poorest 20 percent. But, as Doug Henwood of the Left Business Observer points out, “that looks almost Swedish next to today’s ratio of fifteen times.”[13]

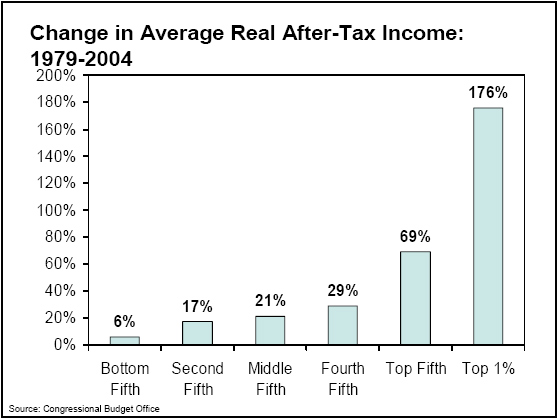

The following are some specific statistics of how redistributive militarism and supply-side fiscal policies have exacerbated income inequality since the late 1970s and early 1980s—making after-tax income gaps wider than pre-tax ones. According to recently released data by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), since 1979 income gains among high-income households have dwarfed those of middle- and low-income households. Specifically:

- The average after-tax income of the top one percent of the population nearly tripled, rising from $314,000 to nearly $868,000—for a total increase of $554,000, or 176 percent. (Figures are adjusted by CBO for inflation.)

- By contrast, the average after-tax income of the middle fifth of the population rose a relatively modest 21 percent, or $8,500, reaching $48,400 in 2004.

- The average after-tax income of the poorest fifth of the population rose just 6 percent, or $800, during this period, reaching $14,700 in 2004.[14]

Legislation enacted since 2001 has provided taxpayers with about $1 trillion in tax cuts over the past six years. These large tax reductions have made the distribution of after-tax income more unequal by further concentrating income at the top of the income range. According to the Urban Institute–Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, as a result of the tax cuts enacted since 2001:

- In 2006, households in the bottom fifth of the income spectrum received tax cuts (averaging $20) that raised their after-tax incomes by an average of 0.3 percent.

- Households in the middle fifth of the income spectrum received tax cuts (averaging $740) that raised their after-tax incomes an average of 2.5 percent.

- The top one percent of households received tax cuts in 2006 (averaging $44,200) that increased their after-tax income by an average of 5.4 percent.

- Households with incomes exceeding $1 million received an average tax cut of $118,000 in 2006, which represented an increase of 6.0 percent in their after-tax income.[15]

Concluding Remarks: External Wars as Reflections of Domestic Fights over National Resources

Close scrutiny of the Pentagon budget shows that, ever since the election of Ronald Reagan as president in 1980, opponents of social spending have successfully used military spending as a regulatory mechanism to cut non-military public spending, to reverse the New Deal and other social safety net programs, and to redistribute national/public resources in favor of the wealthy.

Close examination of the dynamics of redistributive militarism also helps explain why powerful beneficiaries of the Pentagon budget prefer war and military spending to peace and non-military public spending: military spending benefits the wealthy whereas the benefits of non-military public spending would spread to wider social strata. It further helps explain why beneficiaries of war dividends frequently invent new enemies and new “threats to our national interests” in order to justify continued escalation of military spending.

Viewed in this light, militaristic tendencies to war abroad can be seen largely as reflections of the metaphorical domestic fights over allocation of public finance at home, of a subtle or insidious strategy to redistribute national resources from the bottom to the top.

Despite the critical role of redistributive militarism, or of the Pentagon budget, as a major driving force to war, most opponents of war have paid only scant attention to this crucial force behind the recent U.S. wars of choice. The reason for this oversight is probably due to the fact that most critics of war continue to view U.S. military force as simply or primarily a means to achieve certain imperialist ends, instead of having become an end in itself.

Yet, as the U.S. military establishment has grown in size, it has also evolved in quality and character: it is no longer simply a means but, perhaps more importantly, an end in itself, an imperial power in its own right, or to put it differently, it is a case of the tail wagging the dog—a phenomenon that the late President Eisenhower so presciently warned against.

Accordingly, rising militarization of U.S. foreign policy in recent years is driven not so much by some general/abstract national interests, or by the interests of Big Oil and other non-military transnational corporations (as most traditional theories of imperialism continue to argue), as it is by powerful special interests that are vested in the war industry and related war-induced businesses that need an atmosphere of war and militarism in order to justify their lion’s share of the public money.

Preservation, justification, and expansion of the military–industrial colossus, especially of the armaments industry and other Pentagon contractors, have become critical big business objectives in themselves. They have, indeed, become powerful driving forces behind the new, parasitic U.S. military imperialism. I call this new imperialism parasitic because its military adventures abroad are often prompted not so much by a desire to expand the empire’s wealth beyond the existing levels, as did the imperial powers of the past, but by a desire to appropriate the lion’s share of the existing wealth and treasure for the military establishment, especially for the war-profiteering contractors. In addition to being parasitic, the new U.S. military imperialism can also be called dual imperialism because not only does it exploit defenseless peoples and their resources abroad but also the overwhelming majority of U.S. citizens and their resources at home. (I shall further elaborate on the historically unique characteristics of the Parasitic, dual U.S. military imperialism in another article.)

Ismael Hossein-zadeh is an economics professor at Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa. This article draws upon his recently published book, The Political Economy of U.S. Militarism (Palgrave-Macmillan Publishers). Professor Hossein-zadeh is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Notes

[1] William D. Hartung, “Bush Military Budget Highest Since WW II,” Common Dreams (10 February 2007), http://www.commondreams.org/views07/0210-26.htm.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Robert Higgs, “The Defense Budget Is Bigger Than You Think,” antiwar.com (25 January 2004): http://www.antiwar.com/orig2/higgs012504.html.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ismael Hossein-zadeh, “Why the US is Not Leaving Iraq,” http://www.cbpa.drake.edu/hossein%2Dzadeh/papers/papers.htm.

[6] Bill Rigby, “Defense stocks may jump higher with big profits,” Reuter (12 April 2006), http://www.boston.com/business/articles/2006/04/12/defense_stocks_may_jump_higher_with_big_profits/ .

[7] The Center for Public Integrity, “Outsourcing the Pentagon” (29 September 2004), http://www.publicintegrity.org/pns/report.aspx?aid=385.

[8] Scott Shane and Ron Nixon, “In Washington, Contractors Take On Biggest Role Ever,” The New York Times (4 February 2007), http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/04/washington/04contract.html.

[9] Faiz Shakir et al., Center for American Progress Action Fund, “The Progress Report” (6 February 2007), http://www.americanprogressaction.org/progressreport/2007/02/deep_hock.html.

[10] Robert Greenstein, “Despite The Rhetoric, Budget Would Make Nation’s Fiscal Problems Worse And Further Widen Inequality”, Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (6 February 2007), http://www.cbpp.org/2-5-07bud.htm

[11] Ibid.

[12] Richard Du Boff, “What Military Spending Really Costs,” Challenge 32 (September/October 1989), pp. 4–10.

[13] Doug Henwood, Left Business Observer, No. 114 (31 December 2006), p. 4.

[14] Congressional Budget Office, Historical Effective Federal Tax Rates: 1979 to 2004, December 2006; as reported by Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, http://www.cbpp.org/1-23-07inc.htm.

[15] See Tax Policy Center tables T06-0273 and T06-0279 at www.taxpolicycenter.org.