Wall Street and Military Intervention: Citigroup’s Imperial History in Haiti

Citigroup Inc.’s online timeline commemorating its 200th anniversary says little about the Republic of Haiti — and no wonder. While the anniversary campaign for the global financial services giant presents a story of achievement, progress, and world-uniting vision, Citigroup’s first encounter with Haiti is remembered as both among the most spectacular episodes of U.S. dollar diplomacy in the Caribbean and as an egregious example of Washington working at the behest of Wall Street. It is also marked by military intervention, violations of national sovereignty, and the deaths of thousands.

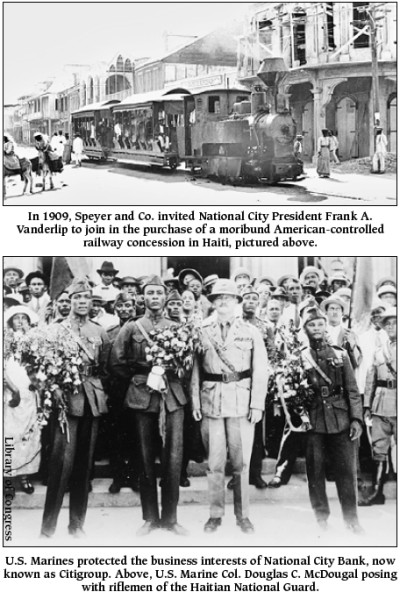

In the early 20th century, the National City Bank of New York, as Citigroup was then called, embarked on an ambitious and pioneering era of overseas expansion. Haiti emerged as one of National City’s first international projects. In 1909, Speyer and Co. invited National City President Frank A. Vanderlip to join in the purchase of a moribund American-controlled railway concession in Haiti.

Vanderlip agreed and the purchase turned out to be a “small but profitable piece of business” for the bank. But Vanderlip wasn’t interested in the acquisition for its short-term returns. He thought the stock would give National City a “foothold” in the country that could lead to a risk-free and profitable reorganization of the Haitian government’s finances.

The next year, Haiti’s government cancelled the contract of the Banque Nationale d’Haiti, giving Vanderlip the opportunity he sought. Chartered in 1880, the Banque Nationale was owned by France’s Banque de l’Union Parisienne and was contracted by the Haitian government to finance the national debt and handle the fiscal operations of the state. It was continually dogged by scandal. Haitian politicians accused its directors of graft and fiscal malfeasance (at one point its foreign managers were jailed) and local political aspirants saw the bank’s currency reserves as a bounty for winning political office.

When a new contract was drawn up, the U.S. State Department intervened, claiming it placed an unfair burden on the Haitian people while giving too much leeway to the French to intervene in Haiti’s internal affairs. They also argued that the new contract didn’t represent the American interests then gunning for a share of Haiti.

As a result of State Department pressure, a new institution, the Banque Nationale de la République d’Haïti, was chartered. The Banque de l’Union remained the majority shareholder, but National City – alongside a number of other American banks and a German one – was offered a minority interest.

The Banque Nationale’s executive decisions were made by a committee split between the Banque de la Union in Paris and the National City Bank in New York. Chairing the New York committee was Roger Leslie Farnham. Farnham had spent a decade working as alobbyist for the corporate law firm Sullivan and Cromwell before Vanderlip recruited him to National City in 1911. Farnham lobbied Washington on behalf of the bank, and eventually took charge of all of its Caribbean operations, including in Haiti.

With the onset of World War I, French interests in the Banque Nationale receded. Farnham assumed a large role in its direction while National City slowly began buying out its stock. At the same time, Farnham was becoming a major influence on State Department policy in Haiti. In 1914, Farnham, who once described the Haitian people as “nothing but grown up children,” drafted a memorandum for William Jennings Bryan, then U.S. secretary of state arguing for military intervention as a way of protecting American interests in Haiti. Sending troops, insisted Farnham, would not only stabilize the country, but be welcomed by most Haitians.

That summer, Bryan cabled the U.S. Consul in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti’s second city, stating that he “earnestly desired the implementation of Farnham’s plan.”

Meanwhile, Farnham and National City worked to destabilize the Haitian government. They refused to pay government salaries over the summer, and in December they ordered the transfer of $500,000 of the Republic’s gold reserves to National City’s vaults at 55 Wall Street in Manhattan. The gold was packed up by U.S. Marines, marched to Port-au-Prince’s wharfs, and shipped aboard the USS Machias to New York.

The bank argued that they owned the gold contractually and were bound to protect it from possible theft. The Haitians saw it as robbery, pure and simple, and indicative of a growing threat to the Republic’s sovereignty.

Threat turned to fact on July 28, 1915. On that day, U.S. Marines landed in Haiti and initiated a period of military rule that would last 19 years. The immediate justifications for intervention included fears of encroaching German influence and a desire to protect American life and property – especially after a spate of factional violence that included the dismemberment of the Haitian president in response to a massacre of his political opponents.

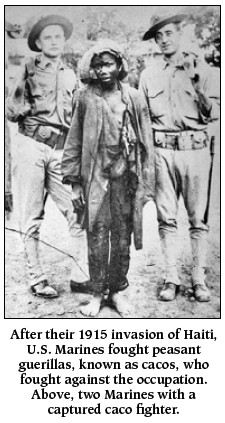

Once the occupation began, it was rationalized as a necessary measure to teach Haitians, citizens of a backward Negro republic, the arts of self-government. Sanitation reforms were enacted, education was promised, public-works projects were planned, and a national guard, later mobilized by François Duvalier to maintain control of the country, was established. In the short term, however, the most pronounced labor of the Marines was counter-insurgency. They waged a “pacification” campaign through the Haitian countryside to suppress an uprising against the occupation led by the cacos, peasant guerillas. It left thousands dead, and countless others tortured, maimed or homeless, while caco leader Charlemagne Peralte was assassinated.

For National City, the occupation provided ideal conditions for business, offering the bank the authority to reorganize Haitian finances just as Vanderlip had envisioned in 1909. By 1922, National City had secured complete control of the Banque Nationale and floated a $16 million loan refinancing Haiti’s internal and external debts. Amortization payments were effectively guaranteed from Haiti’s customs revenue and the loan contract was backed up by the U.S. State Department.

Haiti proved a lucrative piece of business for National City during the twenties. Yet by the beginning of the next decade, they began to reconsider their ownership of the Banque Nationale. Following protests that pressured the State Department to disentangle itself from Haiti, the Marines departed in 1934. National City soon followed. Fearful of losing the State Department’s protection, and wary of public criticism of their activities, the bank’s executives sold the Banque Nationale de la République d’Haïti to the Haitian government in 1935 – reluctantly closing a profitable chapter of Citigroup’s imperial history.

Peter James Hudson is an assistant professor of history at Vanderbilt University. An earlier version of this essay appeared on Echoes, the business history blog of Bloomberg.com edited by Stephen Mihm.