Violence in Cinema: “Torture Porn”: World Cinema at its Lowest Ebb

Interrogation by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin (Oil on canvas)

You walk in to a very large darkened room with a high ceiling. There is a large audience watching in anticipation. A story unfolds before your eyes, in vivid colour. It is the story of a good person who was captured and tortured. The torture is shown in 3D and in metaphor. The audience is hushed and contemplative. Despite the horrors of the torture the protagonist of the story eventually escapes and returns to his friends who are overjoyed, if not a bit shocked at his wounds. But his return signals to all in the audience that there is hope in this world despite the daily horrors.

Of course, the possibly of hope is one of the main differences between the Catholic Mass and certain modern films.

While torture is not new in cinema its depiction has become progressively (or should I say regressively?) more realistic and graphic.

A Serbian Film

What were once vices are the fashion of the day. Seneca

The relatively new genre of torture porn is being highlighted once again by the arrival of A Serbian Film, a film of unspeakable horrors with absolutely no hope. This film has been described as a film about politics as the director defended “his choices by saying that the film represents the molestation of the Serbian people and that you have to feel the violence to understand it”. According to The Guardian:

“the British Board of Film Classification were less convinced and demanded 49 individual cuts that amount to nearly four minutes of screen time. ‘The film-makers have stated that A Serbian Film is intended as an allegory about Serbia itself,’ admitted a BBFC spokeswoman. ‘The board recognises that the images are intended to shock, but the sexual and sexualised violence goes beyond what is acceptable under current BBFC guidelines [for an 18-certificate].’” [1]

The extreme nature of the film has even caused it to be dropped from the Film4 Frightfest film festival, “the UK’s premiere fantasy and horror film festival.” [2] (For those with a very strong stomach here is a link to a review of A Serbian Film, but be warned, it doesn’t have two disclaimers for nothing:http://www.moviesonline.ca/2010/12/torture-porn-redefined-dressing-serbian-film/). Calls for censorship have come from reviewers and groups that would normally be quite liberal about such films. The consensus seems to be that the extreme nature of the content of the film undermines any political message.

There have been many films in this genre over the past few years: Saw (2004) [3], Hostel (2005) [4], Wolf Creek (2005) [5] etc. Torture porn has been creeping into mainstream films for some years now with The Life of David Gale (2003) [6], The Passion of Christ (2004) [7] and Casino Royale (2006) [8].

Changing aesthetic

The changing aesthetic of violence can be seen in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998) [9] with three kinds of violence occurring throughout the film. There is an opening 30-minute war scene of the D-Day invasion of Normandy which is executed in a gritty realistic manner and a final battle scene of the soldiers holding off a German counter-attack with a more typical Hollywood war movie aesthetic.

However, there is a scene before the final battle of hand to hand warfare in the ruined houses where one soldier sticks a knife in another lying on the floor and talks quietly to him as he slowly pushes the knife in. This is a different aesthetic from the other two scenes as one starts feel like a voyeur watching how a person dies rather than why. The voyeur aspect is a strong element of the torture porn genre where victimisation, pain and suffering are lingered over.

There has been much discussion about the desensitizing effects of such violence in mainstream cinema on society on the one hand and the grip of the nanny state on the other. However, we live in an unfair society and there is no doubt that whether cinema begets violence or not is an important subject necessitating constant debate. The organisation of society itself creates many frustrations and these can be expressed in many kinds of violence: state violence (e.g. riot police), political violence, sexual violence, criminal violence, blood sports, bullying, structural violence etc.

Aerial Bombardment by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin (Oil on canvas)

Rather than looking at the affects of watching violence on audiences, I would like to look at the ideological impact of violence in films in the context of power and social control in society in general.

In this sense, it is fruitful to look at the prevalence of violence in films from the perspective of the asymmetrical power relations between the victims and the perpetrators. Instead of questioning whether there should be violence or not, we can examine if the violence is justified or not, who ultimately benefits from the violence and whether the violence used is excessive or not.

For example, in Hostel II wealthy men bid for the opportunity to torture and kill. In one scene in Hostel II:

“[Stuart] takes the sack off Beth’s head and explains about Elite Hunting. Stuart tells Beth that the group is a worldwide secret society where wealthy members come to Slovakia to kill people that the organization abducts as a twisted satisfaction for the psychopath members to kill people in various fantasy-like ways for the sole purpose to watch them die and to get the satisfaction of killing a human. All the members are important people of society in every country in the world (politicians, lawyers, doctors, policemen, directors, actors, businessmen, etc).” [10]

Hostel II describes the ultimate ‘service industry’ where the most extreme fantasies can be ‘enjoyed’ if you have enough dough. Thus, in the film it is the elite of society who are seen to enjoy any kind of activity they desire to be indulged in. They can ‘buy’ a victim upon whom they can conduct extreme forms of torture and murder. It is unjustified, excessive violence perpetrated on unknowing victims.

In films where it is ordinary people engaging in violence (aside from violent criminality), it tends to be revenge violence or revolutionary violence.

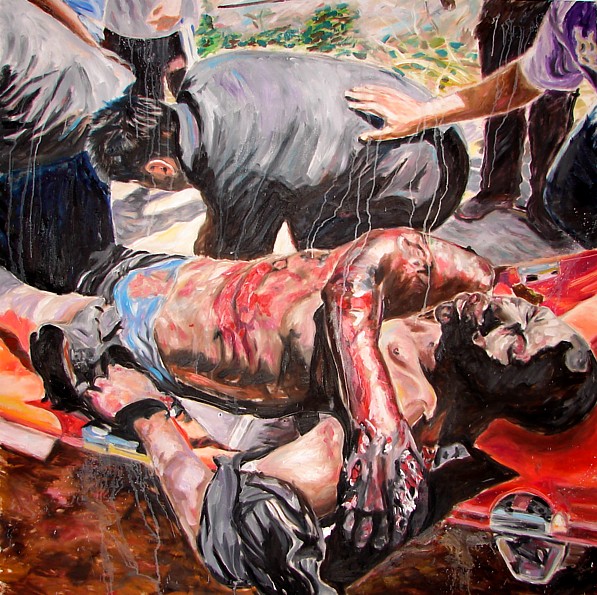

Aftermath of Suicide Bomber, Morgue in Rawalpindi, Pakistan by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin (Oil on canvas)

Revenge violence

Revenge is a kind of wild justice, which the more man’s nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out. Sir Francis Bacon

The problem with revenge violence is that it is anarchic and so can be difficult to stop from spiraling out of control. A lynch mob is an example of violence that is carried out in anger and may result in the group murder of an innocent person.

In cinema, revenge violence can express a collective unconscious of revenge on someone who it was felt had never properly faced justice for their crimes. For example, in Inglourious Basterds (2009) a fantasy of revenge is created through violence which is used against Hitler:

“On her cue, Marcel flicks his cigarette into the pile of nitrate film behind the screen, igniting it. The fire bursts through the screen, causing pandemonium in the auditorium. Just then, Donowitz and Ulmer burst into Hitler’s box and gun down Hitler, Goebbels and the other Nazi leaders.” [11]

Thus a violent retribution is enacted upon those who caused much suffering and death to millions of Jews but who in reality escaped justice through suicide. In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) [12] we see a different form of revenge violence when the torture and violent rape of a woman leads her to seek revenge through reciprocal violence and then becomes a ‘saviour’ of all women when she tracks down a serial killer of young women and refuses to pull him from his burning car.

Revolutionary violence

It is organized violence on top which creates individual violence at the bottom. It is the accumulated indignation against organized wrong, organized crime, organized injustice, which drives the political offender to act. Emma Goldman

Ken Loach’s “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” (2006) [13]

In The Battle of Algiers (1966) frustrations caused by colonial oppression result in political violence by the oppressed, whereby “the torture used by the French is contrasted with the Algerian’s use of bombs in soda shops.” [14]

“The Battle of Algiers” (1966) [15]

In other films there is the calculated revolutionary violence that is used to bring about social and political change in films such as The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) (The Irish War of Independence) [16], Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) (The Spanish Civil War) [17] and Che: Part One (2008) (The Cuban Revolution) [18]. In these films violence is contextualised, directed at specific targets for specific reasons, and always with a long term goal in mind. Whether these films are anti-colonial, anti-fascist or stories of popular uprising they counteract the negative ideology of individualised suffering and torture without hope.

“Che: Part II” (2008) [19]

New cathedrals

It has often been stated that shopping malls are the new cathedrals of society yet the process of film-making has much more in common with church rituals. In the church the mass goers learn of the Christian narrative through the Stations of the Cross (unfolding picture story of the crucifixion), stained glass windows (vivid colour), the Crucifix hanging behind the altar (3D), Breaking of the Bread and Communion (metaphor), Eucharistic Prayer and Apostles’ Creed (the Good News) ending with the Blessing and Dismissal. [20]

In cinemas we watch multi-million dollar block buster movies that are based around a core of a few well-known actors who are the focus of attention over and above minor actors and extras around them. These films follow quite rigid narrative structures that are usually ideologically conservative. The films are then shown all over the world in cinemas with audiences soaking in an ideology which is legitimised by the fame of the primary ‘A-list’ actors.

In the church, the story of capture and torture is balanced by the idea of hope and redemption. The cinema can do the same. It is possible to reject the torture of despair and question the actors and directors who indulge in such film-making while, at the same time, continually asserting our desire for a cinema of hope, of stories that show heroism and courage in the face of the multi-faceted forms of violence and oppression in modern society.

Notes

[1] http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/aug/27/a-serbian-film-frightfest

[2] http://www.frightfest.co.uk/

[3] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0387564/synopsis

[4] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0450278/synopsis

[5] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0416315/synopsis

[6] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0289992/

[7] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0335345/

[8] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0381061/

[9] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120815/

[10] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0498353/synopsis

[11] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0361748/synopsis

[12] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1132620/synopsis

[14] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0058946/plotsummary

[15] http://www.offoffoff.com/film/2004/battleofalgiers.php

[16] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0460989/synopsis

[17] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0457430/synopsis

[18] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0892255/

[19] http://www.munster-express.ie/files/2009/05/che-3.jpg

[20] See: http://catholic-resources.org/ChurchDocs/Mass.htm

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is a prominent Irish artist who has exhibited widely around Ireland. His work consists of drawings and paintings and features cityscapes of Dublin, images based on Irish history and other work with social/political themes (http://gaelart.net/). He is also developing a blog database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world. These paintings can be viewed country by country on his blog at http://gaelart.blogspot.com/.