Vietnam War’s Lasting Legacy in Southeast Asia

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

In Vietnam, the Vietnam War (1955-1975) is known as the “American War,” or the “War Against the Americans to Save the Nation.”

In 1954, countries at the United Nations in Geneva agreed to hold a general election in the former French colony divided by Cold War alliances. Since the communist north Vietnam wanted to unite the country, the United States did not want an election and backed the south in a bid to stop communism from gaining ground in Southeast Asia. A year later, the Vietnam War broke out.

Active involvement of U.S. troops in Vietnam began from 1965 and by 1969, more than 500,000 U.S. military personnel were fighting in the war that had turned into the bloodiest conflict since World War II.

For many in the West, this period evoked an anti-war movement that transformed the social and cultural landscape. But for countries in Asia, including Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, the 20-year war left a lasting legacy of terror and destruction long after the fighting stopped.

As historian Nick Turse documented in his harrowing 2013 book “Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam,” the defining feature that makes memories of this war so difficult for many Americans was the relentless violence against civilians: the massacres of women, children and the elderly, rapes, indiscriminate bombardment, burning down of villages and routinized torture.

One of the most infamous incidents of mass atrocities against civilians by U.S. troops was the My Lai massacre in March 1968, when U.S. troops killed some 500 civilians in a murderous spree the U.S. military would deliberately cover up and spin as a victory over the Viet Cong.

A mother and her child after the burning of their village near Saigon during the Vietnam War. /CFP

Matthew Dallek, associate professor at George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, said the massacre and the cover-up are a particularly dark moment in the history of modern America, which raised big questions about whether the U.S. was capable of defending freedom, democracy and human rights in far-flung places.

“The government’s claim of ‘defending’ Southeast Asia from atheistic communist aggression had become a cruel and paradoxical hoax,” Dallek said.

According to a study by Harvard Medical School and the University of Washington, there were 3.8 million violent war deaths, of which 2 million were civilians.

The cruelty against civilians was more than a collection of isolated incidents, but the official policy. According to former Secretary of State John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran, in his 1971 testimony before the Senate, such atrocities were “crimes committed on a day-to-day basis with the full awareness of officers at all levels of command.”

This unpopular war sparked widespread anti-war protests in the West. A large number of U.S. servicemen returning from Vietnam were left traumatized for life.

But the horrors were far from over when the Americans evacuated Saigon, the former capital of south Vietnam, in 1975. More than 40 years on, the impact of U.S. chemical warfare in Vietnam has been astonishing.

U.S. Air Force UC-123B prowler aircraft spray Agent Orange defoliant over south Vietnam during Operation Ranch Hand in March 1969. /CFP

During the war, U.S. forces dumped 50 million liters (13 million gallons) of Agent Orange, an herbicide containing highly toxic dioxins, across Vietnam’s forests and farmlands, exposing an estimated 4 million Vietnamese people to the dangerous chemical.

The Red Cross of Vietnam estimates that nearly 1 million people suffered severe health complication and disabilities due to exposure. Hundreds of thousands of children were born with serious birth defects. The environmental destruction is immeasurable and irreversible.

Around 2.8 million U.S. veterans were also exposed, the U.S. Veterans Administration said. While American victims of Agent Orange are eligible for government compensation, along with multi-million-dollar settlements from lawsuits brought against manufacturers of the chemical, no one has been held officially accountable for the suffering of Vietnamese victims.

Two babies with birth defects caused by Agent Orange exposure are abandoned at a temple in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, July 25, 2011. /CFP

Decades after the war, people in Southeast Asia are still getting killed by detonation of live bombs and mines left in the region during war time. In 2018, the New York Times reported that more than 300,000 tonnes of unexploded ordnance (UXO) remain in Vietnam, while Vietnamese media claimed there were 725,000 tonnes of UXO scattered across the country.

It is estimated that more than 20 percent of the land in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam is contaminated by UXO. Extensive areas of the three nations continue to be unavailable for agriculture, industry or habitation, hindering the economic development of the countries.

Laos is thought to be the most heavily bombed country in the world per capita as a result of the Vietnam War. According to the Geneva-based Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, there have been over 50,000 UXO casualties in Laos since 1964, including over 29,000 deaths. Around 40 percent of victims are children. The problem is so dire in Laos that the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) even made UXO clearance a development goal for the country.

Despite continued efforts by the three countries, the U.S. and the international community, it reportedly could take 100 years or more to clear the countries of UXO.

War legacy issues like Agent Orange contamination and UXO have played an important role in the relations between the U.S. and Vietnam, and also neighboring countries affected by the Vietnam War. Since the 1990s, the U.S. has provided assistance to cleanup efforts and victim relief in Southeast Asia via various channels.

However, the ongoing challenges present a number of issues for the U.S. Congress. For instance, there is the question of whether a similar policy should be applied to U.S. wars in other parts of the world, such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

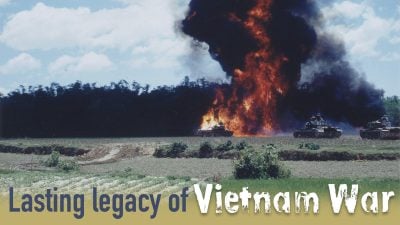

Featured image: U.S. tanks use flamethrowers in a field during the Vietnam War in 1970. /CFP