Video: Prospects of War in the Persian Gulf Region

Since Donald Trump has been in office, Iran and the United States have faced the worst crisis in their relations since the fall of the pro-American Shah regime in 1979. The situation escalated in early May, when US sanctions came into full force. Tehran’s leaders made a number of harsh statements against America and its main ally in the region, Israel, after which an increase in pro-Iranian formations near American positions was noticed. At the beginning of May, Iran partially suspended the fulfillment of its obligations under the JCPOA [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – the 2015 nuclear deal] and abandoned the restrictions pertaining to enriched uranium and heavy water. In addition, Iran made it clear that, in the case of an escalation in tensions, it is able to destabilize oil supplies throughout the Persian Gulf.

After a series of suspicious attacks on oil tankers on May 12 and June 13, the United States blamed Iran without providing any hard evidence. The diversions were given as the reason for the strengthening of the American military presence in the region. By tightening the pressure on the Islamic Republic, the United States aims to create the conditions necessary for the building of the anti-Iranian Middle Eastern strategic alliance (MESA) – a military bloc similar to NATO, for which America now expects loyalty and support from its local allies.

Iran is a major irritant to the two key American allies in the region – Saudi Arabia and Israel. Therefore, after the attacks, both countries immediately joined in the US accusations against Iran.

Israel is worried about Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Iranian military forces on the border with Syria. At the Herzliya Conference on July 1 Mossad chief Yossi Cohen said that in light of shared opposition to Iran and ‘Islamist terror groups’ a potentially one-time-only window of opportunity had opened for Israel to achieve a regional peace agreement. The work is already in progress. Yossi Cohen said that Jerusalem was to open a foreign ministry office in Muscat amid warming relations with Gulf nations. Further, Israeli Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz made a rare visit to Abu Dhabi, which does not have official ties with Israel, for a two-day UN climate meeting. While there, he met with an unnamed Emirati official to discuss bilateral ties as well as the Iranian threat.

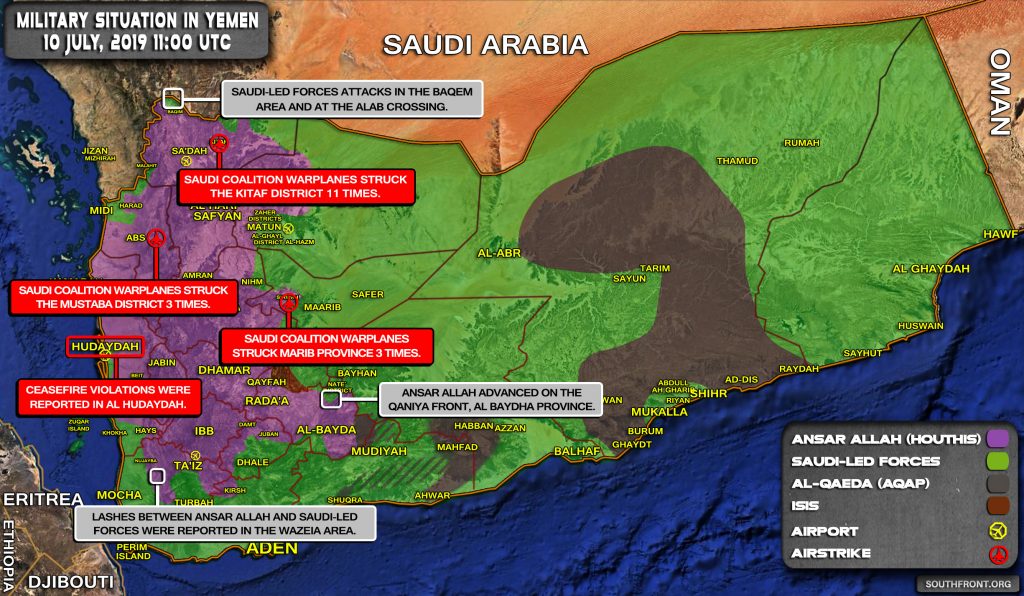

Saudi Arabia, in particular, is worried about Iran’s regional activities as represented by the Ansar Allah movement (the Houthis) in Yemen. On June 12, the Houthis launched a cruise missile at Abha international airport in southern Saudi Arabia. The Houthis also carried out successful raids in the southern Saudi province of Asir on June 17 and 18. In the course of the advance, they destroyed at least 11 vehicles of Saudi forces and captured loads of weapons. Saudi warplanes and attack helicopters carried out several airstrikes on Houthi positions in southern Asir in an attempt to repel the attacks. However, the airstrikes were not effective.

After the Khashoggi case, the US Senate resolutions to stop support for the war in Yemen and the Stockholm truce agreement under Hodeida, it is unlikely that many are willing to go to war. Therefore, the Saudis are trying to draw international attention to Iran. The Crown Prince said that the Kingdom supported the re-imposition of US sanctions out of the belief that the international community needed to take a decisive stance against Iran. A senior UK official said an unnamed Saudi intelligence chief and the Kingdom’s senior diplomat Adel al-Jubeir pleaded with British authorities to carry out limited strikes on Iranian military targets. According to the official, the failed Saudi lobbying efforts took place only a few hours after Donald Trump had aborted a planned attack on Iran on June 22. On May 30, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman went on an anti-Iran tirade during an emergency meeting of Arab leaders hosted in Mecca. He urged the use of all means to stop the Iranian regime from regional interference.

The UAE has its own vision. Despite anti-Iranian statements made jointly with Saudi Arabia during the past three regional summits, the Emirates are not rushing to blame Iran for these attacks. UAE minister of state for foreign affairs Anwar Gargash stated that there is not enough evidence that Iran was responsible. Even after Iran hit an American drone on June 20, the Emirates continued to call for a diplomatic resolution of the crisis through negotiations. Anwar Gargash stressed that the crisis in the Gulf region requires collective attention. At the end of June, four Western diplomatic sources reported that the UAE had reduced troop levels in Yemen, where they are fighting the Houthis at the side of the Saudi Arabia, as the exacerbation of tensions threatens their own homeland security. An anonymous high-ranking Emirati official confirmed this information, but cited other reasons for the movement of troops. Responding to a question about whether tensions with Iran are behind this step, he said the decision was more connected with the cease-fire agreement in Hodeida in accordance with the UN-led peace pact, reached in December.

In turn, Oman offered its mediation services in deescalating US-Iranian tensions. On June 12 Oman’s minister of state for foreign affairs Usuf bin Alawi visited Iraq. Spokesman Ahmad Sahhaf said that bin Alawi discussed solutions for regional challenges and added that Iraq had become a pivotal country because of its strategic relations with both Iran and the United States.

A week later, a similar visit was paid by Kuwait‘s Emir Sheikh Sabah Al Ahmad Al Sabah. He met with Iraqi President Barham Salih and Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi. The leaders called for “wisdom and reason” in dealing with tensions in the region to avoid an escalation leading to clashes. Kuwait’s Permanent Representative to the UN Mansour Al-Otaibi did not mention who might be behind the attacks and called for an unbiased investigation into the matter, instead of jumping into hasty and baseless conclusions.

Despite its anti-Iranian sentiment, Bahrain fears Iran’s threats to close the Strait of Hormuz, through which about 30 percent of all exported world crude oil passes. Bahrain along with Qatar and Kuwait can supply oil for export only through this strait, since these countries have no other access to the sea. On June 15, at the summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), Foreign Finance Minister Khaled bin Ahmed Al-Khalifa urged to refrain from measures that could undermine confidence and security on the main energy routes.

Although some Gulf countries do not like the regional activities of Iran, none of them want a real war. Three recent regional summits showed the differences between the countries of the Persian Gulf. In final statements, the Arab states expressed complete solidarity in opposing Iran, condemning all the recent attacks in the region, and supported any further Saudi Arabian actions to defend its territory. Thus, Jordan’s Ambassador Sufian Al-Qudah, stated that “any targeting of the security of Saudi Arabia is aimed at the security of Jordan and the entire region”. Making a thinly veiled threat, he also stated that Amman supports all measures taken by the Kingdom to maintain its security and to counter terrorism in all its forms and manifestations.

The meetings were supposed to show Tehran the unity of the Arabs and their readiness for decisive actions, but this did not work out. The wording of all three outcome documents varied in their rigidity with the expansion of the members of the meeting. For example, Kuwait and Oman did not participate in the formulation of the final GCC communiqué at all.

At the Arab League meeting, no mention was made of the attacked ships in the communique and in order to condemn Iran the UAE even had to include the topic of disputed islands. The entire final part was focused on the Houthis rocket attack on Saudi Arabia, so the aggression against one of the countries was formally condemned. With the expansion of the number of participants the contradictions about their complaints against Iran were growing. The shelling of Saudi territory by Yemeni resistance forces is a compromise issue, since none of the participating countries wants to be attacked. The OIC summit brought total disappointment to the supporters of the anti-Iranian bloc: it was no longer possible to adopt all these resolutions there.

As for Qatar, along with Kuwait and Oman it is not only not participating in the aggressive anti-Iranian rhetoric, but it is also beginning to express dissatisfaction with the efforts of Saudi Arabia and the UAE to dominate the region. Many expected that the attendance of Qatar at the summits was a sign of improved relations between Doha and the other Gulf states. But it was more a message that the blockade will not prevent Qatar from participating in region-wide meetings. In the aftermath of the summits, Qatari Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani said that “no concrete steps” had resulted and questioned the unity called for by the other countries amid the ongoing blockade.

The achievement of a tough pan-Arab condemnation of Iran, which John Bolton had insisted on, failed even despite all the guarantees of protection he gave during his visits to the KSA and the UAE on the eve of the summits.

This desire of the United States to strengthen anti-Iranian sentiment is connected to the fact that the growing tensions allow Washington to increase military spending. As for foreign policy, the United States would be justified in continuing their anti-Iran and pro-Israel policy, as well as in strengthening its presence in the Middle East. The growing threat to maritime security will lead to increased logistics costs for key oil consumers. This situation directly affects China, one of the key consumers of oil, and European countries with large industrial potential, such as Germany.

However, many countries in the region understand that the United States will not be able to protect them in the case of a serious conflict. Bolton couldn’t please his Arab friends with the resumption of US military assistance to the forces of the Arab coalition, which had been frozen due to humanitarian concerns and the Khashoggi case. The US Senate approved 22 resolutions, which proscribe the United States from concluding weapons deals with Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries without the prior approval of Congress. Bolton made it clear that the Arabs shouldn’t rely on the participation of US troops in the fight against the Houthis. Before Trump, the United States could easily unleash wars “for democracy”, but now the consequences of the war with Iran cannot be predicted, and even the United States cannot be confident of victory.

In the case of an attack, Iran could destroy vital facilities in the Persian Gulf, such as oil refineries, hydropower plants and desalination systems. The new military doctrine of Iran adopted in 1988 aims to transfer the war to enemy’s territory. For example, Iran could use Syria, Lebanon and Gaza as a launching pad to strike Israel, similar to the way it uses Yemen against Saudi Arabia.

As mentioned above, some countries are worried that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are trying to dominate in the region. A fully-fledged war could lead to a repartition of influence and the rise of the pro-Iranian Shi’a, which would collapse the oil-rich Sunni monarchies. As a result the world might be overcome by an economic crisis, perhaps even more global than all the previous ones.

Thus, in the short term both sides are likely to continue to slide into a sluggish confrontation until something happens that could move the conflict off the ground. Trump will not make major adjustments in his policy toward Iran. Firstly, because of fears of image loss on the eve of the presidential election 2020. Secondly, because of the position of his closest allies in the region.

The Islamic Republic, for its part, will not meet the US halfway. Iran sees any concessions as a potential threat to its survival. Remembering what happened to Saddam Hussein after he agreed to the US disarmament requirements, the Iranian leadership will never make the same mistake. Despite mutual threats, neither will the United States deploy a full-scale war, nor will Iranian units strike at the regional positions of the Americans. A war will begin only if one of the parties crosses the red line, but so far no side is ready to do so. Therefore, it is still premature to talk about the new Gulf War.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

We call upon Global Research readers to support South Front in its endeavors.

If you’re able, and if you like our content and approach, please support the project. Our work wouldn’t be possible without your help: PayPal: [email protected] or via: http://southfront.org/donate/ or via: https://www.patreon.com/southfront