Victimhood and the Nigerian Civil War

The concatenation of violence in Nigeria from 1966 to 1970, a train of events which involved communal fighting, army mutinies and a civil war, is correctly viewed as a period during which the ethnic Igbos of the country’s south east bore the overwhelming brunt of the suffering. They died at the hands of rampaging mobs of their fellow citizens, as well as through the munitions employed by the Federal armed forces. They were also the victims of mass starvation. This suffering was of course a focus of Western news reporting of the conflict and of the machinery of propaganda employed by the secessionist state of Biafra.

Today, their plight is still referred to by pro-secessionist Igbo activists, as well as by the wider community of Igbos through the commemoration of events such as the Asaba Massacre of October 1967. But there is another often neglected side to the story, that is, of those Nigerian civilians, including non-Igbo minority communities, who were co-opted into the Biafran project and who suffered at the hands of Biafran troops and paramilitary organisations. The reasons for this neglect is multifaceted, but it is one which is documented and in need of acknowledgement if Nigeria is to come to terms with the terrible human rights abuses of that dark chapter in its history.

The enduring image of the Nigerian Civil War for many around the world was perhaps the sight of naked Kwashiorkor-ridden children wracked by the pain of starvation. They were Igbo children caught up in a war in which the secessionist state of Biafra had been quickly encircled and an air and sea blockade instituted by the Federal Military Government. The brutality of the conflict was encapsulated by the filming of a British television company of the execution of a captured Biafran man by an officer of the Federal army who had promised to spare his life. That incident provided a living, breathing image to go along with the reports of atrocities which had preceded the civil war and which were apparently continuing.

But the story of innocents suffering was not a totally one-sided one. A forgotten aspect of the civil war concerns the human rights abuses perpetrated by the Igbo-dominated Biafran side against minority groups within what had been the former Eastern Region of Nigeria, as well as against other Nigerian ethnic groups in the Mid-Western State when it was temporarily occupied by Biafran forces.

A missing aspect of the narrative concerns the ill-treatment meted out to minority groups within secessionist Biafra such as the Efik, Ijaw, Ogoja and Ibibio. It would be remiss not to remind that these groups were targeted along with Igbos in the northern part of the country during the explosions of communal violence in May 1966, as well as between September and October of that year. But they would later suffer persecution and human rights abuses at the hands of the largely Igbo Biafran Army.

Much of this stemmed from real and imagined sympathy on the part of members of these communities for the Federal cause. The minority communities of the old Eastern Region had after all campaigned for the creation of more states; something which the Nigerian Head of State, Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon had done in May 1967. And while some non-Igbo officers such as Lt. Colonel Phillip Effiong, an Ibibio, served in the Biafran armed forces, others such as Colonel George Kurobo had defected to the Federal side.

An example of abuses against Biafran minorities concerns that of the Ikun people, who were suspected of collaboration. This led to detentions, looting and raping by Biafran troops in Ikunland. Many males were rounded up and ‘disappeared’, while others were shot to death.

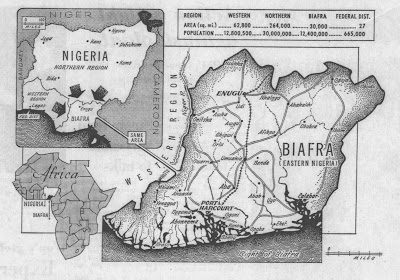

Map produced in the Friday February 16th 1968 edition of the Canadian newspaper, the Windsor Star

The Ikun are minuscule in numbers and the Biafran felt particularly threatened by the larger ethnic groups from Calabar, Ogoja and Rivers provinces where the pre-war agitation for states of their own to be carved out of the Eastern Region had been particularly strong. Many communities within these areas received the attention of the Biafran security apparatus. They were subjected to constant surveillance and some were imprisoned and subjected to torture. They were also frequently subjected to accusations of being ‘saboteurs’. And when the Federal armies encroached further into Biafran-held territory, the fear of minority fifth-columnists led to the wholesale eviction of communities such as the Kalabaris from their homelands. They were relocated to Igbo towns and cities to live in refugee camps.

Another example of this anti-minority sentiment was reflected by the activities of the Biafran Organisation of Freedom Fighters (BOFF), a paramilitary organisation created to protect Biafran communities, but which used operations to turn on minority groups.

One of the most publicised war crimes committed by the Biafrans occurred when Federal troops landed in Calabar in October 1967. About 167 civilians in detention were lined up and executed by Biafran soldiers. The Nigerian Consulate in New York published details of this atrocity as an informational advertisement in the New York Times as part of the propaganda war with the Biafrans, whose own propaganda machinery at home, and operating internationally under the auspices of the Geneva-based Markpress public relations firm, always had the edge over the Federal side.

The propaganda war also included several false claims made by the Biafran side about massacres said to have been perpetrated by the Federal army including one in Urua Inyang. This was noted in the December 6th 1968 edition of the Ottawa Citizen. That same article, one syndicated by the Toronto Star, also recorded the direct testimony of a Red Cross worker in the Calabar sector of the war in which he stated that Biafran soldiers shot civilians when retreating. This was an often repeated modus operandi.

Biafran Army atrocities in another theatre of war, namely that of the Mid-Western part of the country, also needs recounting. For it was here that the infamous massacre by Federal troops of civilians in the Igbo-town of Asaba took place. The Asaba Massacre, which occurred between October 5 and 7 in 1967, is seen as a continuum of the anti-Igbo pogroms of 1966. Other opinion contextualises it in relation to the ill-treatment meted out to non-Igbo communities in the Mid-West State during its occupation by Biafran forces.

During the Biafran invasion in August of 1967, some soldiers had paused to kill northerners who lived in the Hausa Quarter of Asaba; this in apparent revenge for the aforementioned anti-Igbo attacks in the Northern Region. And in other parts of the temporarily conquered Mid-West, non-Igbos were subjected to torture, imprisonment and death on suspicion of having sympathy for the Federal cause. Rape, extortion and seizure of property were common. The conduct of Biafran troops, who were styled as a liberation army, was marked by acts of indiscipline particularly in the urban centres of Benin, Sapele and Warri. In Warri, the men of the 18th Battalion went on looting sprees, searching for anything that they could convert into cash.

The Biafran side had taken the Mid-West’s neutral position, or at least, its refusal to support the Eastern Region’s secession as an effectively anti-Igbo stance. The relationship between the Igbo military administrators and the non-Igbo Mid-West populace was from the outset an antagonistic one. For instance, one E.K. Iseru, a lawyer of Rivers origin who was based in Warri would testify at a tribunal hearing that he was once stripped naked and detained for three days without food because he was on record as having agitated for the creation of Rivers State. When he protested about his hunger, one of his captors retorted that “there is no food for Hausa friends.”

When the Biafran occupiers began to lose ground, their paranoia increased. Each set back on the battlefield was blamed on saboteurs, and in the desperate circumstances of continual retreat, the policies of the Biafrans turned to draconian, inhumane solutions. The murder of non-Igbos intensified. In Abudu, over 300 bodies were found in the Ossiomo River and on 20 September 1967, many non-Igbos were slaughtered at Boji-Boji Agbor. And at Asaba, Ibusa and Agbor non-Igbos were taken into custody by Biafran soldiers and transported in two lorries to a rubber plantation along the Uromi-Agbor Road where they were put to death.

In the tit-for-tat atmosphere of war, it is perhaps no surprise that an estimated 200 Igbos lost their lives when the Federal takeover of Benin City began on September 21st. Later, mobs in places such as Warri and Sapele would turn on the Igbos. Many Igbos, including the erstwhile administrator, Major Albert Okonkwo who had declared the Mid-West to be the “autonomous independent sovereign republic of Benin”, fled eastwards for their lives.

That the suffering of non-Igbo minorities became something of a forgotten history is not in question. It is also not unique. Most people are likely more familiar with the Jewish Shoah of the mid-20th century than they are with the Armenian genocide earlier on in that century. Fewer still are aware that the first genocide of the 20th century took place in South West Africa (present day Namibia) where Kaiser-era German colonists sought the extermination of the Herero and the Nama peoples.

Nigeria is of course not the only nation to have lingering wounds over a civil war as recent events in both the United States and Spain remind. Much of the discourse remains venomous and resolutely uncomprehending of an understanding of the position of both sides in the war. Many prefer to take a particularistic view with a tendency on the part of Biafran diehards to deny the occurrence of these events and insist on the primacy of Igbo victimhood.

It is an extremely unsatisfactory state of affairs that is part and parcel of an often banal, yet poisonous, tribally-motivated discourse. This only serves to polarise attitudes and perpetuate enmities from one generation to the other.

When referring to the toxic exercise of apportioning ethnic responsibility for the murderous revolution in the Russian empire in 1917 and the ensuing bloody civil war, the Russian Nobel Laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once spoke of the need to avoid “scorekeeping” and comparisons of moral responsibility. He said, “Every people must answer morally for all of its past – including that past that is shameful. Answer by what means? Where in all this did we go wrong? And could it happen again?” These words speak to the spirit in which Nigerians ought to engage in when examining their past. The fact that minorities of the former Eastern region suffered brutal ill-treatment at the hands of both Federal and secessionist forces gives their plight an added poignancy. History owes it to them that their suffering also be acknowledged.

Anything else would be an abrogation of our basic humanity.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Adeyinka Makinde is a writer based in London, England. This article was originally published on his blog, Adeyinka Makinde.