US Wants to Increase Special Agents in Latin America Under Anti-drug Speech

Washington’s “war on drugs” is advancing in Latin America. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) recently asked the US Congress for a new budget, valued at more than 3 billion dollars, to improve its operations abroad and help to prevent narcotics from entering American territory. As expected, the main countries mentioned in the Agency’s plans are Latin American nations.

The DEA application is being evaluated for the coming year. If approved, it will represent an increase of more than 15% over the 2020 budget – a truly bold move that indicates that the U.S. Department of Justice is willing to act more vigorously against drug trafficking. At first, the amount would be used to establish new judicial interception programs in regions such as Honduras and the Bahamas, which are on the international trafficking route. But what is most surprising is the proposal to buy a King Air 350 plane, valued at almost 50 million dollars, for explicit espionage purposes in regions considered strategic.

Although it is the focus of operations, Latin America is not the only region where the US intends to operate. Countries like Afghanistan appear on the DEA’s blacklist alongside Mexico and Colombia. In order to cover the entire trafficking route, the DEA suggests in its project the creation of hundreds of new posts. More than thirty of these posts would be intended for special agents only. Other thirteen posts would be created just to improve the quality of the current DEA programs and offices that are specialized in attacking, intercepting, and dismantling international criminal organizations that supply drugs to American distributors and users - among these, three posts are aimed at Mexico and other Latin countries, which would cost 1.5 million dollars.

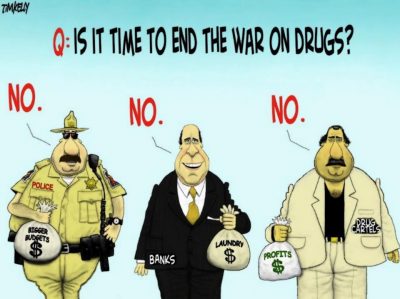

Obviously, every sovereign national state must use all its available means to combat trafficking and prevent the entry of illegal substances into its territory. At first, the DEA project has merit and deserves approval because it requires resources to fight a major threat to the existence of any nation, which is international trafficking. But are these resources really used to fight drug trafficking?

A few months ago, the Venezuelan National Guard captured a plane that carried drugs in its airspace. The plane probably did the transport linking Colombia to some other region of the trafficking route. Most impressive, however, is that the aircraft contained official American identification. Although it is a curious event – especially considering that the US has started a crusade against Venezuela accusing the Maduro government of being involved in trafficking – it is far from an isolated case. This is just one example of the countless times the US has been accused of being officially involved in drug trafficking activities.

Police departments, the CIA and the American Armed Forces have often been accused of having been involved in criminal activities since at least the 1970s. In addition to the episodes in Latin America, Afghanistan, a country cited by the DEA in its new project, is known to be a territory rich in opium poppy fields and, coincidentally or not, had an exponential increase in its drug production after the arrival of the Americans in 2001.

For any attentive expert, this is not a secret: several world powers have implicit or explicit involvement in drug trafficking. This is part of the network of interests that feed the “deep state” of each country. Authorities who should fight organized crime get involved with such organizations and create networks of connection between the state and crime. When they grow, these networks start to dispute their interests in a more incisive way, deeply interfering in the direction of institutional politics. Thus, the so-called “Narco States” are created around the world.

Colombia, for example, a historical ally of the US, is an example of an explicit Narco State, where criminal networks dominated the public sphere and institutional politics. Colombian President Ivan Duque Marquez has been seen several times with members of criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking. Washington supports Ivan despite his explicit involvement in trafficking, because it sees him as an ally against Venezuela – a problem that for American interests is worse than trafficking. In the same way, this happens in the performance of the intelligence departments against the traffickers. In order to obtain information and form strategies against some cartels, the agents involved in the operations form alliances with organizations that are enemies of those being investigated – because they consider them a “lesser evil”. After a while, such alliances become deep and can no longer be broken.

So, if American interests do not exactly coincide with the end of drug trafficking and if Washington has allies involved in trafficking and some of its authorities are closely linked to criminal organizations around the world, especially in Latin America, what would be the intention of expanding the human and material resources of the anti-drug departments so widely? The reason is simples: to increase control of strategically selected regions.

From the moment that we have a discourse on combating drugs and a broad material apparatus, we can do anything with such an apparatus and justify it under this discourse. Sending US special agents to several countries equipped with war weaponry, spy aircraft and several other resources is extremely advantageous for Washington. And when it has the discourse on fighting drugs, everything is allowed.

In many regions of the planet, especially in Latin America, the “war on drugs” works as a minor version of the “global war on terror” (in its American way): a legalistic and humanitarian discourse created to guarantee the interests of the American Hegemony.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on InfoBrics.

Lucas Leiroz is a research fellow in international law at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Featured image is from InfoBrics