US Supreme Court, From Rights to Repentance: Norma McCorvey and Roe v Wade

“I wasn’t the wrong person to become Jane Roe. I wasn’t the right person to become Jane Roe. I was just the person who became Jane Roe, of Roe v Wade.”— Norma McCorvey with Andy Meisler, I am Roe: My Life, Roe v Wade (1994)

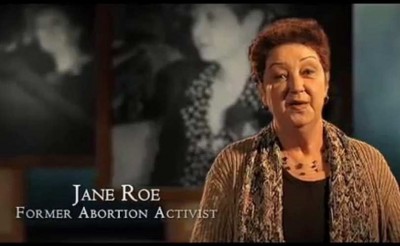

The late Norma McCorvey changed US legal and political history as the plaintiff “Jane Roe” in the 1973 US Supreme Court decision Roe v Wade. The case has become the shorthand for bodily autonomy, dignity, shield of an expansive idea on privacy. The due process clause, so the judgment went, contained “a concept of personal liberty” while “the penumbras of the Bill of Rights” retained in its awe-inspiring mystery “a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy.”[1]

For the US women’s movement, it was more than just legal stardust: it was solid gold, providing nuggets for the rights revolution. In the wording of the decision, the privacy right was “broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy”.

As with anything, where there are rights, seething, sometimes irreconcilable conflict, exists. Even Roe was not absolute in its abstract renderings, with the judgment noting that States could still ban third-trimester abortions while also regulating abortion “in ways that reasonably related to maternal health” in the second. It was only for the first trimester that “the abortion decision and its effectuation [had to be] left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman’s attending physician.”

Rights, in short, are not seen as creatures born and isolated. Duties follow with weighted feet, reciprocally attaching themselves. In the US cosmology of rights, there was always going to be the indignant counter that duties also mattered, perhaps even more, and that the foetal cult would seek a counter-reformation.

That counter-reformation was reflected in the actions of the plaintiff herself. McCorvey had sued the state of Texas after seeking an abortion on falling pregnant again. “Back in 1973, I was a very confused 21 year-old with one child and facing an unplanned pregnancy.”

She had every reason to be, living through what the New York Times termed “a Dickensian nightmare.” She had been “the unwanted child of a broken home, a ninth-grade dropout who was raped repeatedly by a relative, and a homeless runaway and thief consigned to reform school.”[2] The poster child, it was implied, of American dysfunction: married at 16, bisexual though mainly lesbian, three children by three men, all given up. There were the rough jobs, the drugs, the alcohol.

It was the sort of confusion that provided carrion for pro-life movements eager to swoop in on doubt. One such emotional vulture was Jeanne Mancini, president of the March for Life, who suggested that McCorvey had been “coerced” and “encouraged to lie about the situation being the result of rape.”

By the 1990s, McCorvey’s rights perspective had morphed, transferring to the foetus on the wings of a newly found faith. Being harangued as a “baby killer” and an ample number of death threats did their trick. Abortions came to be seen as forms of sanctioned murder advanced by damaged and confused mothers easily influenced, aided by a judicial pronouncement of grim reaper selfishness.

Roe No More was established; McCorvey spent time working for Operation Rescue. She attended rallies, wrote books. God seemingly crept up on her with divine intrusiveness (pro-lifer goons helped), then captured her conscience with terribly sweet reminders of what amounted to crime, an afterlife more dramatic than a Hieronymus Bosch triptych. It was “upon knowing God, I realized that my case which legalized abortion on demand was the biggest mistake of my life.”

Guilt is hard to measure, but various desert religions obsessed by apoplectic moralism do their best to bring out calculations, however artificially generated. McCorvey, for Tom Peterson, president and founder of VirtueMedia, struggled with a heavy “heart that 50 million babies had died because of her participation in this case.”

With zeal, Peterson’s soul hunting outfit launched JaneRoe.com which runs on the rich fuel of confessions – from mothers who have regretted their abortions. Finding that mothers may be damaged from their experience, it is also appropriate to exploit them for it. (Monotheistic morality is such a treat.)

Fittingly, all matters of legal and social debate eventually become aggressive industries in the turbulent richness of US soil: the right to abortion, the right of the foetus, and guilt itself, transmuted into a market of regret, doom and the blessed promise of confession.

Praise from pro-life groups was abundantly heaped after word of McCorvey’s passing spread. “Ultimately,” claimed Marjorie Dannenfelser, president of the pro-life group Susan B. Anthony List, “Norma’s story after Roe was not one of bitterness but of forgiveness. She chose healing and reconciliation in her Christian faith.”[3]

Dannenfelser’s remarks are very much readied against the rights industry fashioned around abortion (“Norma suffered tremendously at the hands of those who cared more about the institution of abortion than this courageous woman’s life”), and in them is also contained the mania about liberty and notions of false emancipation. McCorvey “overcame the lies of the abortion industry and its advocates and spoke out against the horror that still oppresses many.”

The battle continues. States persist in campaigns that seek to impose regulatory burdens that are designed to eliminate the exercise of abortion altogether, less in name than form. Clinics and those providing abortions remain favourite targets. Needless cant, and moral rage, continues.

Even beyond Roe, there is a fundamental point about US legal identity, one irritably rife with dissent and theatre in using the court system. Great battles and poor law (for hard cases make bad law) have been the result, be it over guns or electoral campaign spending. But such cases can obliterate the individual, leaving in their stead a mythology of rights. There could be few better examples than McCorvey in her quest to litigate, then repent.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes

[1] http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/410/113.html

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/18/obituaries/norma-mccorvey-dead-roe-v-wade.html?_r=0

[3] http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/life-conversion-of-roe-v-wades-norma-mccorvey-remembered-35081/