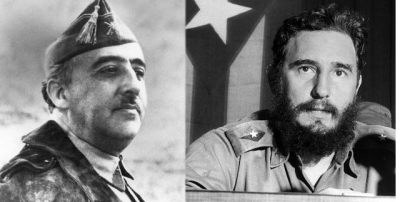

US Support for General Franco’s Regime and the Spanish Dictator’s Commercial Links to Cuba

Despite being a “rabid anti-Franquista” for many years, the Cuban leader Fidel Castro would develop some grudging respect for Spain’s Fascist dictator, General Francisco Franco.

Following Castro’s 1959 ousting of the American-backed tyrant, Fulgencio Batista, Washington ordered all Latin American and European nations to ostracize revolutionary Cuba. With the Caribbean island facing near-total isolation, and with worse deprivations to come, Castro noted that Franco “was the only one who didn’t bend to Washington’s demand”. It would prove an unlikely lifeline for the new Cuba.

Castro said,

“Franco didn’t break off relations. That was a praiseworthy attitude that deserves our respect and even, at that point, our gratitude. He refused to give in to American pressure. He acted with real Galician stubbornness. He never broke off relations with Cuba. His attitude in that respect was rock-strong”.

Franco was himself born in the Atlantic coastal town of El Ferrol, Galicia, in north-west Spain. During the Spanish-American War of 1898, Spain’s forces were routed by America in the decisive Battle of Santiago de Cuba – a naval conflict on Cuba’s southern coast, sealing America’s victory in the war.

As the battle neared its end, an entire Spanish squadron was destroyed by the Americans, which Castro highlights was “from El Ferrol” (Franco’s birthplace). Over 340 Spanish sailors were wiped out, and almost two thousand captured, while the US suffered just a single casualty. It was one of the greatest humiliations in Spanish history and ensured Cuba’s transfer from one imperial power (Spain) to another (America) – coined “the liberation of Cuba” by Western scholars.

Castro expounded that the defeat

“was a terrible blow to the military’s pride, and to all of Spain’s pride. And it happened when Franco was a boy in El Ferrol. Franco must have grown up and read and heard all about that bitter experience, in an atmosphere of despondency and thirst for revenge. He may even have been present when the remains of the defeated fleet were returned, the soldiers and officers who’d been humiliated and thwarted. It must have left a profound mark on him”.

It may explain the potential disregard in which Franco held America. This despite him enjoying support from certain US businesses during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) – like the Texas Oil Company, and automobile manufacturers Ford, Studebaker, and General Motors, who in total provided 12,000 trucks to Franco’s men, with fuel supplies.

Though officially protected by the US from 1953 on (Pact of Madrid), Franco’s Spain never gained membership of the American-run military alliance NATO – despite neighboring Portugal being among the first countries to join NATO in 1949, under the right-wing Antonio Salazar dictatorship. Spain only acceded to NATO in 1982, almost seven years after the Fascist autocrat’s death.

Nor did Franco ever set foot in the US, or grace the sacred halls of the White House, unlike other dictators (the Shah, Suharto, Pinochet, etc.). In Madrid, Franco met presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Richard Nixon – while in 1972 he saw Ronald Reagan in the Spanish capital when the latter was Governor of California, but never returned the favor on any occasion.

Elsewhere, Franco would have been aware that most white Cubans themselves are of Spanish extraction. Castro’s father, for example, was born in Galicia, the same Spanish territory as Franco.

As a result, Castro’s sound defeat of US-backed forces during the Bay of Pigs invasion (April 1961) – and later resistance to American terror – is likely to have been viewed by Franco, which Castro remarked, as “a way to secure Spain’s revenge”, while having “restored the Spaniards’ patriotic sentiments and honor”, after the disasters of the Spanish-American War. “That historical, almost emotional element, must have influenced Franco’s attitude”.

Despite repeated criticism of Franco’s policies, Castro was somewhat reliant upon him, admitting that “nobody was going to make me break them off [relations]”. Franco was easily the largest importer of not only Cuban tobacco, but also of rum and sugar. Had Franco severed ties as the Americans demanded, the Cuban Revolution’s future would have been thrown into further doubt.

Moreover, in return, Franco sold trucks, machinery, and other commodities such as fruit to Cuba – while Spain’s national airline continued its routine operations from Madrid to Havana, the only then such flights between western Europe and Cuba. In late 1963, the new American president, Lyndon B. Johnson, threatened Franco with legislation which would cut aid to nations assisting Castro’s government. Again, the intimidation was rebutted.

Franco, known as El Caudillo [the Leader], had long been noted for his obstinance. Decades before, despite heated demands from Adolf Hitler for Spain to enter the Second World War – including a famous meeting between the dictators in October 1940 at Hendaye, south-western France – Franco declined his German counterpart’s overtures. This was at a time when Hitler, known for his persuasive methods, was at the pinnacle of his power, with much of mainland and northern Europe under his control.

Franco’s refusal to commit seriously to the war enraged Hitler, who had provided crucial military aid to Franco during the Spanish Civil War, along with Benito Mussolini. Unable to pin Franco down, Hitler said he would “rather have three of four teeth pulled” than meet him once more; and Indeed, they would never see each other again.

The Nazi dictator, addressing Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Armaments Minister Albert Speer, further denounced Franco in January 1943 as, “a fat little sergeant who couldn’t grasp at my far-reaching plans”.

Hitler remarked that,

“during the civil war the idealism was not on Franco’s side, it was to be found among the Reds. Certainly they pillaged and desecrated, but so did Franco’s men, without having any good reason for it – the Reds were working off centuries of hatred for the Catholic Church, which always oppressed the Spanish people. When I think of that I understand a good many things”. (Hitler’s comments were recounted by Speer in December 1950 at Spandau prison, West Berlin).

Franco’s main commitment to the German military effort comprised of dispatching “the Blue Division” to the Eastern Front, in June 1941 (as the war continued its numbers rose to 45,000 troops).

However, by the mid-1940s, Hitler’s “far-reaching plans” lay in ruins, and Franco’s refusal to weigh fully in behind the Germans surely saved his neck. As Castro discerned of Franco, “He was unquestionably shrewd, cunning – I don’t know whether that came from his being Galician; the Galicians are accused of being shrewd”.

Franco’s near four-decade rule, until his death in November 1975, was also one of bloodshed and repression, particularly in the early years. Franco had said in 1938, “One thing I am sure of, and which I can answer truthfully… wherever I am there will be no Communism”. He ruthlessly followed through on such a declaration with policies responsible for killing up to 400,000 people, as Spanish Republicans and other left-leaning activists were massacred by Francoite forces.

As Castro noted of the Spanish despot, “the number of people he killed, the repression he imposed… his name is associated with a tragic period in Spain’s history”.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Global Village Space.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from Global Village Space