US Presidential Primaries, Changing Political Culture, The Role of Movements

Movements on the right and left are changing the political culture. Their impact can be seen in the Democratic and Republican primaries, but the media does not report it.

BALTIMORE — Confusion reigns in the Democratic and Republican primaries. Huffington Post political reporters write, “It’s Time To Admit: Nobody Knows Anything About The 2016 Campaign,” now that “the old ‘rules’ of presidential politics no longer seem to apply.”

Why the confusion? Media pundits have not given credit to the popular movements on both the right and left. This election cycle is showing the impact of social movements on the primary campaigns — both in the polling results and in the candidates’ rhetoric.

Tea Party and Occupy change the political culture

On the Republican side, Tea Party anger is showing itself. Republicans co-opted this movement, but its members are dissatisfied with elected Republicans and are turning to non-politicians. Why are they angry? Because the core of Washington politics continues: crony capitalism, wherein government writes the rules and doles out the cash for their big business donors.

One example of many was giving President Barack Obama fast track trade authority to negotiate deals that undermine our democracy, economy and sovereignty. Voters know that these crony capitalist trade deals, like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is larger and farther-reaching than NAFTA, have been bad for the U.S. economy. Speaker John Boehner was forced to resign because of his heavy-handedness in insisting Republicans support fast track for Obama and punishing those who led opposition to it.

Occupy Wall Street protesters.

The role of corporate Democrats has been evident in the Democratic Party for a long time. The Democratic Leadership Council, founded by Bill Clinton, Al Gore and others, was successful at destroying Howard Dean, an insurgent, but definitely not a radical one. The DLC has evolved into the Third Way Democrats, whose donors are funding former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and will seek to ensure the defeat of Sen. Bernie Sanders.

The Democratic Party needs a complete overhaul away from its pro-corporate, “Third Way” stance if it wants to be in synch with the grassroots. The Occupy movement and its offshoots — Fight for $15, Black Lives Matter, OUR Walmart, Strike Debt, and United We Dream, among others — hold views opposite from corporate Democrats.

Tea Party activists cheer during the “Exempt America from Obamacare” rally, on Capitol Hill, September 10, 2013 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Tea Party activists cheer during the “Exempt America from Obamacare” rally, on Capitol Hill, September 10, 2013 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Occupiers were never part of the Democratic Party because the Democrats are in bed with Wall Street, while Occupy saw Wall Street as a root of corruption. The Sanders campaign could not have existed without Occupy changing the corporate political culture. Clinton has had to mould her rhetoric to fit the new political reality. Again, the TPP is one example of many where the “gold standard” TPP has now become unacceptable to the former Secretary of State. Why? The movement that has developed against it is so broad that the TPP is “Toxic Political Poison.”

More revolts are coming as Washington continues on the same corrupt path.

Movements and electoral politics

Police remove activist Margaret Flowers for protesting the Trans-Pacific Partnership during a Senate hearing in January. (Reuters/Kevin Lamarque)

Mass movements need an electoral arm, one that comes out of the movement with candidates who are accountable to the movement. In fact, to help achieve that, Margaret Flowers, co-director of Popular Resistance, will be taking a leave of absence as she seeks the Green Party nomination for the U.S. Senate in Maryland.

The movement needs to build an alternative to challenge the United States’ mirage elections and pro-corporate parties. U.S. elections consist of two corporate candidates running against each other. The two political parties rig the system to prevent insurgent challenges inside the duopoly and to stop third alternatives outside the duopoly.

Movements have a lot of work to do to create real democracy; basics include universal voter registration, uniform ballot access, verifiable voting systems and public funding of public elections. Much more needs to be done to create a representative democratic system that allows for minority parties to have a voice in the legislature, i.e. proportional representation, as well as a break from monopoly voting districts to protect the duopoly. We also need to build more direct democracy like voter initiatives and participatory budgeting. These are a few examples of how the U.S. badly needs to update its electoral system to catch up with world experience.

Experiences outside the US

The U.S. is the most ingrained two-party system in the world; that is not a compliment but a description of a system that does all it can to prevent alternatives to the two corporate parties. People in the U.S. can look at Spain, Greece and even Canada to see how alternatives to the two corporate parties can advance and represent the interests of the people.

In Canada, people were astounded earlier this year to see a third party elected to lead Alberta, the oil capital of Canada. Writing for EcoWatch, David Suzuki describes how the voters gave the New Democratic Party a strong majority in response to austerity measures taken by the Conservative Party that reigned for 44 years in Alberta. The NDP is a long-time third party in Canada that was born out of the labor movement in 1961 and is credited with bringing Medicare to all Canadians. Its first leader, Tommy Douglas, remains the most popular Canadian in history. He explains the futility of two-party politics in this video.

Spain recently held local and regional elections that produced astounding results. The elections took place in 13 of Spain’s 17 regions and included more than 8,000 towns and cities. The ruling parties lost power in many major cities as smaller parties, for the first time, challenged the two dominant parties. Writing for radical online journal ROAR Magazine, Carlos Delclós reported in May:

“On Sunday, May 24, the two parties that have ruled Spain since the country’s transition to democracy in the late 1970s were dealt yet another substantial blow, this time in regional and municipal elections. Nationwide, the ruling Popular Party saw support fall from the nearly 11 million votes they received in 2011 to just under 6 million this year.”

This means that candidates from the Indignado Movement will actually govern. In Barcelona, a “prominent anti-evictions activist Ada Colau won the city’s mayoral race.” In many of the largest cities the mayor will not belong to either of the two major parties. How did these parties build their power? Delclós reported:

“. . . [T]heir roots in prominent local struggles, their independence with respect to the established parties and their willingness to spearhead bottom-up processes seeking a confluence between new or smaller parties, community organizations and political independents around a set of common objectives determined through radical democratic participation.”

The Spanish elections, like the Greek elections earlier this year, are an example of bottom-up, grassroots organizing and power-building. The roots of this success are longer than is often discussed:

“In Catalonia, the Popular Unity Candidacies of the left-wing independence movement have had a notable presence in smaller towns for several years (they also quadrupled their 2011 results on Sunday, for what it’s worth). At the southern end of the country, the Andalusian village of Marinaleda is a well-documented experiment in utopian communism that has been going on for over three decades now.”

The new electoral movement is a “municipal movement,” participants tell their story in a video that provides a “recipe” for such a movement.

People arrive to the main square of Madrid during a Podemos (We Can) party march in Madrid, Spain, Saturday, Jan. 31, 2015. Tens of thousands of people, possibly more, are marching through Madridís streets in a powerful show of strength by Spainís fledgling radical leftist party Podemos (We Can) which hopes to emulate the electoral success of Greeceís Syriza party in elections later this year. Supporters from across Spain converged onto Cibeles fountain before packing the avenue leading to Puerta del Sol square. Podemos aims to shatter the countryís predominantly two-party system and the ìMarch for Changeî gathered crowds in the same place where sit-in protests against political and financial corruption laid the partyís foundations in 2011. Andres Kudacki/AP

As we have seen with Syriza’s election in Greece, governing in a new way is no easy task. In an interview with Alexandros Orphanides for In These Times, Frances Fox Piven, a social movements scholar, discussed the complex challenges in Greece as being “not so much to do with Syriza but with the ability of a nation-state, especially of a small nation-state, and its elected political rulers to determine its own economic policy in a very interconnected and global world, in which the centers of financial power are very ominous and powerful.”

In discussing Syriza, Piven talks about the differences between movements and electoral politics:

“Anybody who is running for an election wants to win enough votes to take the seat for which she or he is campaigning. To do that, they tend to be conciliatory; they don’t want to make any enemies. They want to win just enough to get over the electoral barrier. They tend to be consensual, they tend to not want to make trouble. They want to keep everyone that voted for them last time and add the few more that they need to get over the hump.

Movements are very different. They are dynamic. How they grow, how they succeed is very different. Protest movements in particular do two things. They identify issues that politicians want to ignore, because the politicians want to paste together a coalition that can win. Movement leaders, on the other hand, want to identify the issues that can mobilize people. They don’t care about voting, because we don’t know a movement exists by the number of votes it can get—we know by how many people it can pull into the streets. So movement leaders are attracted to contentious issues that make trouble for the parties.

And movements often have a capacity for disruption, for withdrawing cooperation, for bringing things to a halt, for various kinds of strike actions. Parties don’t do that.”

And that is why many recognize the importance of continuing to build an independent movement even if movement candidates win elections. There continues to be a need to disrupt the system to pressure other forces that seek to block progress.

In Spain, a group of militants who see the declining numbers of people in the streets because of electoral progress are seeking to build new street actions. The group, Apoyo Mutuo (Mutual Aid), has doubts about the electoral path and wants to return to popular horizontalism outside of government. They see their work as parallel to Podemos, not in reaction to it but because “politics cannot be limited to the election of representatives at the ballot box every four years. We can’t delegate our responsibility; as a pueblo we need to be active agents in the decision-making process.”

The US electoral system

The U.S. is very different from Europe. Each country in Europe is the size of one state in the U.S. Countries in Europe have systems where even parties that get a minority percentage of votes can be represented in parliament. While many countries have two parties that dominate the political system, there is a greater possibility of participation.

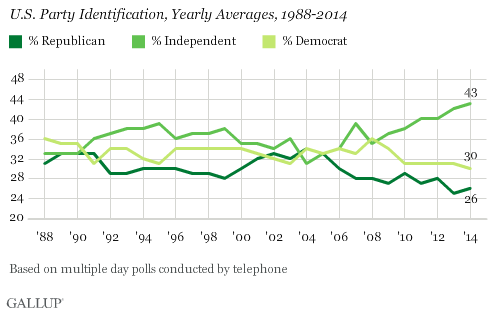

This June an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll found that 50 percent of Americans consider themselves independent and fewer than 30 percent align with either major party. A 2015 Gallup poll similarly found arecord high number of Americans — 43 percent — consider themselves independents, with only 30 percent considering themselves Democrats and 26 percent considering them Republicans.

The independent nature of U.S. voters is not reflected in elections, which makes it very difficult for alternatives to the duopoly to participate. At the same time, elections are funded by a shrinking group of the extremely wealthy. The U.S. is now widely recognized as an oligarchy, where big business and moneyed interests rule, and where democracy is a mirage.

There have been some recent examples at the local level where people from outside of the duopoly have won elections. Most notable is Kshama Sawant, the Seattle City Council member, who Chris Hedges describes asthe “most dangerous woman in America.” Sawant ran with Socialist Alternative, winning 93,000 votes in a citywide race. Sawant came out of the Occupy Movement, fought housing foreclosures and made the Fight for $15 her signature issue. Sawant is up for re-election on Nov. 3 this year; she won the first round of voting in August with 52 percent.

In 2013, Ohio showed a break between the Democrats and labor. Two dozen city councilors were elected on an“Independent Labor” ticket. Lorain County AFL-CIO President Harry Williamson explained: “When the leaders of the [Democratic] Party just took us for granted and tried to roll over the rights of working people here, we had to stand up.”

In 2007, Richmond, California, elected a Green mayor, Gayle McLaughlin, with Greens, independents and progressive Democrats controlling the City Council through the Richmond Progressive Alliance. Big Oil failed in its attempts to defeat them in last year’s elections.

The confusion of the Bernie Sanders campaign

Bernie Sanders, a lifelong independent, is running for president in the Democratic primaries and pledging to support whomever the Democrats nominate if he is not elected. He has entered a rigged Democratic primary system that has successfully blocked insurgent candidates in every election in the last 35 years. The rigging begins with super delegates who make up 20 percent of the delegates needed for nomination, it includes the frontloading of primaries so there are 23 states voting in March requiring hundreds of millions of dollars. And this year they limited debates to only six, when in 2008 there were more than two dozen. This is all designed to stack the primary in favor of establishment candidates like Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden.

Hillary Rodham Clinton, right, and Sen. Bernie Sanders, of Vermont, speak during the CNN Democratic presidential debate Tuesday, Oct. 13, 2015, in Las Vegas. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Howie Hawkins, the recent New York Green Party gubernatorial candidate, writes in “Bernie Sanders is No Eugene Debs” that Debs, the five-time Socialist Party presidential candidate between 1900 and 1920, understood that it is essential for a movement to have its own political vehicle as a matter of principle. Hawkins recognizes that Sanders is good on most domestic issues (not as good on foreign policy) but:

“… [H]is positions on the issues is secondary to the question of whether his politics are helping the working class act for itself or subsume itself under the big business interests in charge of the Democratic Party. By entering the Democratic primaries with the promise of supporting Clinton as the lesser evil to the Republicans, Sanders is not helping the working class to organize, speak and act for itself.”

Sanders has called for a revolution against the billionaire class, but accomplishing that inside a political party owned by Wall Street and other big business interests is an absurdity.

While Sanders is misleading people to stay inside the Democratic Party, he is doing useful education on domestic economic issues. This is valuable to the movement’s task of building national consensus. But, when Sanders loses, which is a near certainty in the rigged Democratic Party primaries, people need to understand the problem is not his positions on the economy but the corruption of the Democratic Party. People need to flee the party and support a third-party alternative like Jill Stein, who is likely to be the strongest third-party candidate in 2016. This is not a wasted vote — though the media will try to convince people that it is. It is voting for what you want and help building an alternative to the corporate duopoly.

How independent movements and third parties have won transformational change

In his article, Howie Hawkins points out that from the 1840s to the 1930s there was a series of independent parties tied to movements to end slavery, secure voting rights for women, allow the development of unions, empower workers, and break up monopolies. The combination of an independent movement and independent electoral politics built power. In 1936, the unions decided to work within the Democratic Party, undermining both independent politics and the union movement.

Ralph Nader in his campaign vehicle during his 2008 presidential bid. (AP/Lisa Poole)

The Nader campaigns of 2000, 2004 and 2008 raised the banner of the “Tweedledum” and “Tweedledee” nature of the two parties. Now the American public is catching on, with a majority being independent of the corporate duopoly. The combination of an independent mass movement and independent electoral politics is once again on the horizon. We already see the movement creating confusion in the duopoly; if the movement continues to grow, an independent electoral movement will follow to accomplish the task of the era – end corporate rule and bring economic, racial and environmental justice.

Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers co-direct Popular Resistance, @PopResistance.