US Plans to Break Up China: CIA Funding for Terrorists, Narco-trafficking and Proxies

The “loss” of China in 1949 was perhaps the biggest blow to strike American hegemony in the post-World War II era, and it is felt increasingly to this day. During the past 70 years, Washington’s strategy towards China has been to destabilise and fracture one of the world’s oldest and largest nations. US governments have spent hundreds of billions of dollars in an attempt to re-establish their authority over China. These imperialist policies have clearly failed to attain their objectives.

Nevertheless US efforts to undermine Chinese power have been steadily growing over the past 30 years, in part spurred on by the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991, partially also due to China’s increasing clout.

The well informed Brazilian historian, Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, wrote that,

“The CIA’s operations sought to do the same to China, as they had done to the Soviet Union during the war in Afghanistan: Fight their enemy via proxies, i.e., through third parties such as terrorist organisations and countries like Turkey, a puppet state that nourishes pan-Turkish and pan-Islamic ideas”. (1)

US plans to destroy communism in China include attempts to break the country apart from its largest provinces, like Tibet and Xinjiang, both within China’s internationally recognised borders. Xinjiang, an ethnically diverse territory of north-western China, is well over twice the size of France. Xinjiang is sparsely populated, much of it consists of desert terrain, it is criss-crossed by towering, snow-filled peaks and lies far from any coastline. Xinjiang is rich in raw materials; 25% of China’s known oil and gas reserves are located there, while the area holds 38% of the nation’s coal deposits. (2)

Xinjiang is of vital strategic and economic importance to China. It stands as the Chinese government’s bridgehead into Central Asia, through which the old Silk Road passed along centuries before, connecting China to as far away as the Mediterranean. Beijing has driving ambitions to link Kashgar, in western Xinjiang, 1,200 miles southwards to the Pakistani port city of Gwadar. Lying on Pakistan’s southern coastline, Gwadar is of major significance by itself and is a central component of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – an infrastructural project instigated by China in 2013, and which is undergoing gradual implementation.

The CPEC is a key part of the landmark Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), designed and led by Beijing; the first phase of the CPEC’s construction has at last been completed in Pakistan (3). It is hoped that this program will spur industrial development across Pakistan, something which the US government has not undertaken there, relying instead on its traditional gunboat diplomacy of military aid.

Gwadar will be part of China’s “string of pearls” bases being built elsewhere in the Indian Ocean, primarily for commercial purposes (4). Beijing wishes to project its strength deep into the lucrative Persian Gulf for the first time in modern history. This would undercut US power, which has weakened appreciably from its high point in the mid-1940s, when Washington owned about half of the world’s wealth.

Nearby Iran, for years China’s largest trading partner, wants to establish a connection between Gwadar and its own port at Chabahar, in southern Iran, close to Gwadar. Pakistan and Iran share a lengthy frontier and, historically, these neighbours have a collaborative understanding.

China’s strengthening relationship with Pakistan and Iran is likely to be a significant occurrence in international affairs – and it is causing some alarm in Washington. Pakistan, a nuclear power like China, is already a member of the Beijing-run alliances, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), while in 2015 Iran joined the AIIB. The construction of pipelines linking Gwadar to both China and Iran, would greatly reduce the time and distance that raw materials have to travel; especially for the Chinese, whose oil shipments traverse the high seas over many thousands of miles, taking between two to three months to arrive.

Moniz Bandeira, professor emeritus of history at the University of Brasilia, observed how,

“A pipeline from Xinjiang to Gwadar would reduce this distance to 1,600 miles. These initiatives point to the formation of a geopolitical axis, a valuable card for China to play in the Great Game in Central Asia and the Middle East, associating itself economically with Pakistan and Iran, a country which China offered 60 million euros to rebuild the port of Chabahar, 43 miles from Gwadar”. (5)

The Middle East and Central Asia are the most valuable and strategically important regions on earth, containing most of the world’s oil or gas reserves. Central Asia, a sprawling, remote landmass bordering China and Russia, holds an abundance of sought after natural resources like copper and iron ore. If Beijing can increase its influence in the Central Asia/Middle East domains – by continuing to pursue infrastructural investments – there is no doubt this will place China in a particularly strong global position, and lead to further US decline.

America is using its financial muscle in a so far unsuccessful effort to shift Pakistan away from China. US-friendly lobby groups in Islamabad are attempting to undermine the CPEC, by labelling it as a Chinese “debt trap”; but the majority of Pakistan’s people favour warm relations with Beijing. After all, China is a country they have a border with to the north-east. Moreover, Washington’s drone warfare campaign in Pakistan has been far from popular, to put it mildly. Another of Beijing’s goals, in linking Gwadar to China, would allow the Chinese government to import oil shipments from the Arabian sea – therefore avoiding altogether the Strait of Malacca, off Malaysia’s coast, which is patrolled by warships of the US Navy.

America is using its financial muscle in a so far unsuccessful effort to shift Pakistan away from China. US-friendly lobby groups in Islamabad are attempting to undermine the CPEC, by labelling it as a Chinese “debt trap”; but the majority of Pakistan’s people favour warm relations with Beijing. After all, China is a country they have a border with to the north-east. Moreover, Washington’s drone warfare campaign in Pakistan has been far from popular, to put it mildly. Another of Beijing’s goals, in linking Gwadar to China, would allow the Chinese government to import oil shipments from the Arabian sea – therefore avoiding altogether the Strait of Malacca, off Malaysia’s coast, which is patrolled by warships of the US Navy.

Moniz Bandeira writes that,

“Beijing’s plan to link the port of Gwadar to Xinjiang, advancing on the Arabian Sea and thus overcoming the strategic dependence on the Strait of Malacca, was probably the fact that led the NGOs – led by the National Endowment for Democracy, the CIA, the Turkish MIT, the Mossad and MI6 – to promote instability in the region, inciting separatist threats and revolts like those in Urumqi [northern Xinjiang] (2009), so as to contain China’s expansion towards the Arabian Sea and the oil resources that fueled the industrial powers of the West”.

Pious Western concern for human rights in Xinjiang acts as a smokescreen, in order to obscure the major geopolitical stakes pertaining to Xinjiang and surrounding areas. Similar disquiet is not expressed about the incomparably worse human rights violations committed by Washington post-1945, and her allies, like Saudi Arabia and Israel. Regarding Central Asia, this region’s largest, wealthiest and most important country is Kazakhstan. It shares a broad frontier with Xinjiang to the east. Kazakhstan contains considerable quantities of oil, gas and uranium. It was surely no coincidence that in September 2013 China’s new president, Xi Jinping, announced whilst visiting Kazakhstan that a “new Silk Road” was about to be laid through Central Asia.

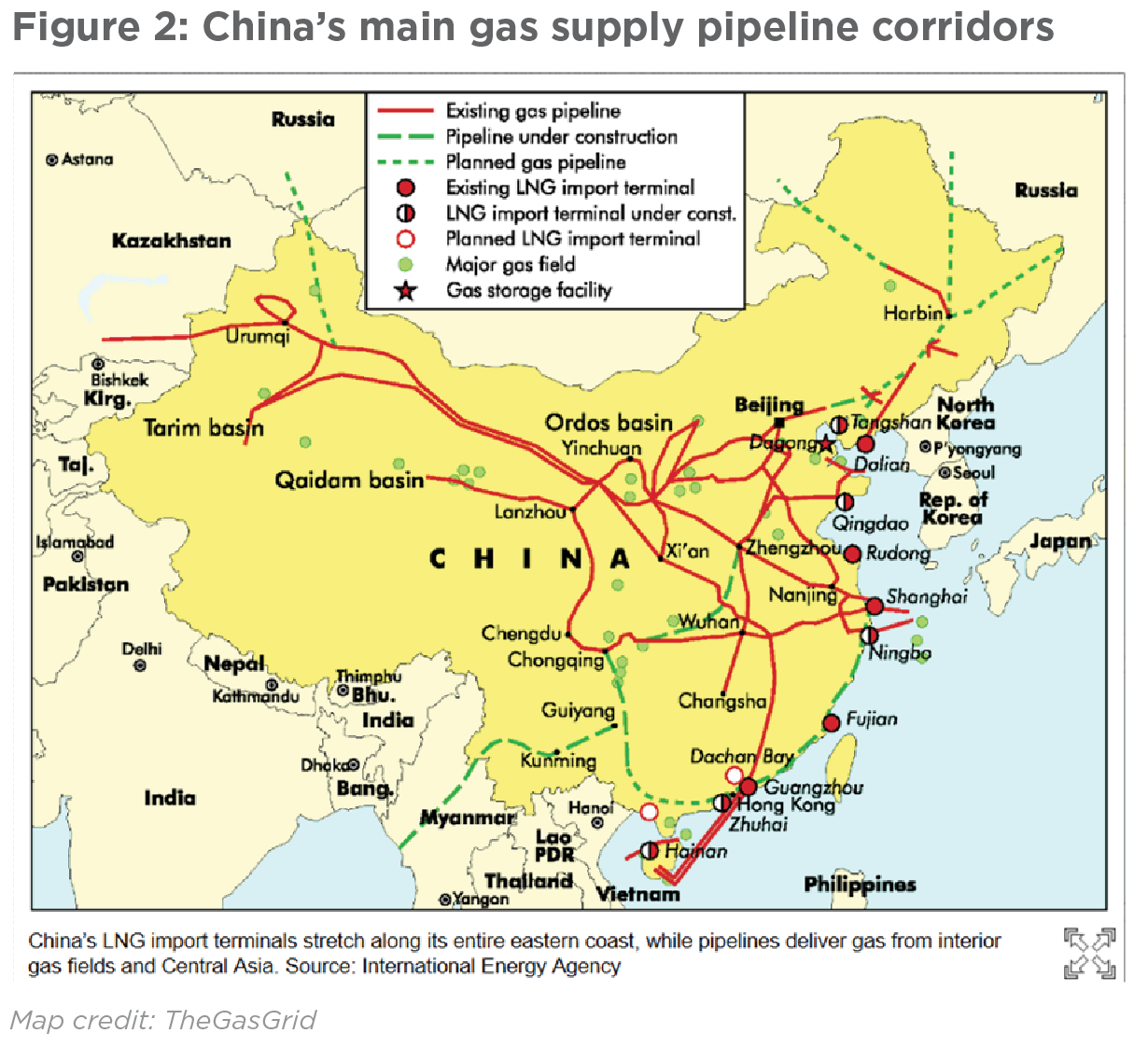

Early this century, Beijing started assembling the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline, which has reached 1,400 miles in length. It provides China with around 20 million tons of oil each year, flowing across the border into Xinjiang, rendering US interference impossible. The erection of this pipeline has helped to copperfasten ties between China and Kazakhstan, who are close allies.

In addition there is the Central Asia-China gas pipeline, a brainchild of Beijing’s. Construction began in August 2007, and it now runs across hundreds of miles of remote, pristine land, from Turkmenistan through to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and on to Xinjiang. The Central Asia-China gas pipeline is Beijing’s largest source of gas imports, and these projects have enabled China to spread its influence throughout Central Asia. The Central Asian countries, with the exception of Turkmenistan, are members of the SCO and the AIIB, which are headquartered in Beijing.

Long before the September 2001 9/11 atrocities against America, the CIA and Pentagon were supporting terrorist operations by extremist Islamic networks with links to Osama bin Laden, in Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Balkans (6). The US was for example using Turkish, Pakistani and Saudi operatives to promote instability in Central Asia, which had been part of the USSR for over half a century until its collapse, with the Americans thereafter moving in. The CIA was involved in drug trafficking (mainly heroin), illegal arms sales and money laundering in Central Asia, Turkey and the Balkans.

By the end of the Cold War, Washington was stepping up its backing for secessionist groups in Xinjiang. The US has for decades recognised the critical nature of Xinjiang, due to its position within China’s frontiers and proximity to energy rich Central Asia. Control over raw materials, like oil and gas, has been a leading tenet of US foreign policy since the early days of World War II.

As the Soviet Union was disappearing, the CIA in 1990 began sponsoring terrorist groups with separatist plans for Xinjiang; like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), an organisation led by extreme Uyghur fundamentalists with past ties to Al Qaeda and the Taliban (7). Between 1990 and 2001 the ETIM, later known as the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), committed more than 200 acts of terrorism in China; such as murderous assaults on market places and public transportation vehicles like buses, along with targeting Chinese government officials for assassination. These terrorist attacks left scores of people dead, while the assailants received funding from the CIA. (8)

Although China has internal demographic issues, one decisive advantage it holds over the West is that it has largely avoided the neoliberal onslaught. There are almost 400 billionaires in China, but the government retains much of its control over big business. Unlike in North America and Europe, the majority of corporations in China are state-owned, including the 12 largest which consist mainly of banks and oil companies. (9)

The continued unrest in Hong Kong, a diminutive area in south-eastern China, can be traced to the British takeover of that territory in the early 1840s. Hong Kong was transformed into a British military outpost, and colonised for more than 150 years. For most of that period, London directly ruled Hong Kong by dispatching governors and expatriate civil servants. These policies had a westernising influence on Hong Kong’s inhabitants, an imprint which lasts until today. Hong Kong, which is densely populated and has ample wealth, is culturally and economically different from mainland China on many levels.

US governments have sought to exploit this friction. Since 2014 the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) has funnelled at least $30 million into Hong Kong so as “to identify new avenues for democracy and political reform” (10). Many hundreds of “pro-democracy protesters” in Hong Kong have been photographed waving American flags and donning other US paraphernalia. (11)

The NED was established in 1983 under the Reagan administration, and receives most of its funding from the US Congress. It has a notorious legacy of meddling in nations across different continents. In March 2018 Stephen Kinzer, an experienced American journalist, described the NED as “the National Endowment for Attacking Democracy”. The long-time NED president, Carl Gershman, said two years ago that China is “the most serious threat our country faces today” and “We have to not give up on the possibility for democratic change in China and keep finding ways to support them” (12). As a consequence, much of the NED’s focus is centred on China, and sitting in the NED boardroom are interventionist neo-conservatives like Elliott Abrams and Victoria Nuland.

For over a decade the NED has funded exile Xinjiang groups, such as the Uyghur American Association (UAA) headquartered in Washington, and the World Uyghur Congress (WUC) based in Munich. They call for Xinjiang’s complete breakaway from China, to be replaced by an independent state called East Turkestan. This is understandably looked upon by Beijing with grave misgivings. The World Uyghur Congress chief advisor, Xinjiang-born Erkin Alptekin, has past affiliation with the CIA. From 1971 until 1995, Alptekin worked for the US government-run broadcaster, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Returning to Hong Kong, one of its most recognisable figures is Joshua Wong, a 23-year-old student leader and politician. Wong’s separatist aims have enjoyed widespread support from Western politicians and the mainstream press. It can be noted that Wong has increasingly been playing into Beijing’s hands, by publicly aligning himself with the American government; adding fuel to the fire that Wong has become a proxy tool for the US in its bitter rivalry with China.

Last September, Wong travelled the 8,000 mile distance from Hong Kong to New York and Washington, to seek US political backing. He met and had discussions with war-mongering politicians like Marco Rubio, Florida’s Republican senator who strongly endorsed the US-led attack on Libya in 2011. The Hong Kong political party Demosisto, of which Wong is Secretary-General, is said to have a close relationship with the NED. (13)

These ill-advised moves have inevitably damaged Wong’s reputation, while undermining his claims for Hong Kong independence. Wong, in a co-authored article published last month with the Washington Post, claims that China “has revealed its true colours as a rogue state” with its policies towards Hong Kong (14). Wong again urged “the U.S. government to execute the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act” and he called on Washington to “impose sanctions on China”.

Beijing’s actions in Hong Kong have been repressive in recent years, but it remains a mostly free and open society. Hong Kong native Sonny Shiu-Hing Lo, a 57-year-old political scientist and professor, wrote recently that Hong Kong’s elections are for the large part “quite competitive and run according to democratic procedures. There are also important non-party democratic elements in Hong Kong”. Professor Sonny Lo, who emigrated to Canada as a youngster before returning to work at Hong Kong University, could hardly be described as pro-Beijing. Yet he writes that a “strong civil society” still exists in Hong Kong “representing a wide variety of political views” which “are active and influential”. (15)

Professor Sonny Lo notes how the work force in Hong Kong is “particularly well organised” and represented by two rival trade unions. He reveals that “Hong Kong has also maintained its long tradition of a lively, independent press” and that “many newspapers and other media sources… often voice strong criticisms of both the HKSAR [Hong Kong government] and the PRC [People’s Republic of China]”. Despite the press reprovals of China, neither the Chinese-backed Hong Kong administration, nor indeed Beijing, have moved to censure or close down these outlets in Hong Kong.

Focusing on the international scene, facing out to sea China is almost surrounded by US allies and a range of advanced military forces; while there is no Chinese armed presence within sight of US shorelines. Over the past decade, Washington has shifted much of its military might to east Asia in a bid to hem China in and negate its development.

Part of American policy in east Asia, is to keep out of Beijing’s hands the island of Taiwan, an affluent territory less than 150 miles from China’s south-eastern shoreline. The importance of Taiwan to China has similarities to that of Cuba to the United States. Taiwan is a pawn in the US encirclement strategy of China. Again this month a heavily-armed US destroyer sailed provocatively through the Taiwan Strait, mere miles from China’s coast (16). Since 2009, the Obama and Trump administrations have sold around $25 billion worth of military equipment to the US-supported Taiwanese government, from fighter aircraft and tanks to missiles.

Some of this high-tech US weaponry is capable of carrying nuclear warheads, though there is no evidence to suggest there are weapons of mass destruction on the island. Dozens of US nuclear bombs were stationed secretly in Taiwan from 1957 until 1975, including nuclear-armed Matador missiles installed there by the Pentagon from January 1958. China did not develop nuclear weapons until 1964. Under president Trump, the rate of military aid furnished to Taiwan has risen substantially.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Notes

1 Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, The Second Cold War: Geopolitics and the Strategic Dimensions of the USA, (Springer 1st ed., 23 June 2017), p. 68

2 William A. Joseph, Politics in China: An Introduction, Second Edition (Oxford University Press; 2 edition, 11 April 2014), p. 430

3 Dr. Zafar Jaspal, “CPEC: The real danger is US’s policies”, Global Village Space, 20 May 2020

4 Noam Chomsky, Who Rules The World? (Metropolitan Books, Penguin Books Ltd, Hamish Hamilton, 5 May 2016), p. 245

5 Moniz Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 73

6 Moniz Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 67

7 Moniz Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 68

8 Thierry Meyssan, “The CIA is using Turkey to pressure China”, Voltaire Network, 19 February 2019

9 Scott Cendrowski, “China’s global 500 companies are bigger than ever – and mostly state-owned”, Fortune Magazine, 22 July 2015

10 Mary Beaudoin, “The Nature of the Hong Kong Protests”, Consortium News, 26 November 2019

11 Ella Torres, Guy Davies and Karson Yiu, “Why exuberant Hong Kong protesters are waving American flags”, ABC News, 28 November 2019

12 Edward Hunt, “NED Pursues Regime Change By Playing The Long Game”, Counterpunch, 6 July 2018

13 Mnar Muhawesh, “The NED strikes again: How Neocon Money is Funding The Hong Kong Protests”, Mintpress News, 9 September 2019

14 Joshua Wong, Glacier Kwong, “This is the final nail in the coffin for Hong Kong’s autonomy”, Washington Post, 24 May 2020

15 William A. Joseph, Politics in China: An Introduction, Third Edition (Oxford University Press; 3 edition, 6 June 2019), p. 534

16 Al Jazeera, “US warship sails through Taiwan Strait on Tiananmen anniversary”, 5 June 2020