US Hunger Rate Triple That in China

American workers are now three times more likely than Chinese workers to lack the means of feeding their families, according to a startling new report from the Gallup organization. The polling group found that 19 percent of Americans worried about being able to feed themselves or their families, compared to only 6 percent of Chinese.

The Gallup finding showed a near reversal in the proportions of American and Chinese workers at risk of hunger over the past three years, an indication of the shattering impact of the economic slump brought on by the 2008 Wall Street financial crash. In 2008, 16 percent of Chinese said they at times lacked the money to put food on the table, compared to 9 percent of Americans.

Although China has more than four times the population of the United States, the absolute numbers of hungry people are nearly the same: just under 80 million for China, more than 60 million in America. The similarity is particularly stark given that the United States is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of food.

Gallup’s measure of access to basic social necessities like food and health care, the United States Basic Index Score, fell to 81.4 in September, lower than the worst previous mark during the slump, the 81.5 mark hit in February and March of 2009.

The components of this index detail the deteriorating conditions of life for the American working class. From September 2008 to September 2011, the proportion of Americans with a personal physician fell from 82.5 percent to 78.3 percent. The proportion with health insurance fell from 85.9 percent to 82.3 percent. The proportion who said they had enough money to buy food for themselves and their families declined from 81.1 percent to 80.1 percent.

The findings are derived from one of the most comprehensive surveys of international living standards, interviews with 29,000 people conducted each month over the past three years in 150 countries, including 1,000 in the US and 4,000 in China. The survey encompasses 13 questions about access to food, shelter, clean water, health care and other necessities.

For Americans surveyed, the three indices of social well-being that have declined most sharply were all health-related: having a personal doctor, having health insurance, and visiting a dentist.

The proportion of Americans struggling to afford shelter is up sharply as well—11 percent of Americans said there have been times in the past 12 months when they could not afford decent shelter, up from 5 percent in 2008.

This figure is less than in China, where hundreds of millions still live in rural hovels or are migrant laborers in urban areas, but the trend lines are in the opposite direction. Some 16 percent of Chinese said they had trouble affording shelter, down from 21 percent in 2008.

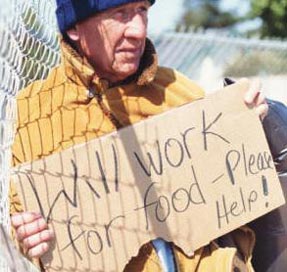

The US figures show the particularly severe impact of the world slump of the past three years, which has driven US unemployment up above the 9 percent level. Some 25 millions American workers are either unemployed or underemployed.

The official US poverty rate, which grossly understates the crisis, is up from 14.3 percent in 2009 to 15.1 percent in 2010, the fourth consecutive yearly increase. The absolute number of those in poverty is far greater than in 1965, when the Democratic administration of Lyndon Johnson launched its “war on poverty.”

The findings of the Gallup study testify to the combined effect of two world-historical processes. The first is the relative decline of American capitalism, whose once-mighty industrial base has shriveled, and with it, the living standards and social conditions of the working class. The second is the globalization of the world economy, which is leading to the convergence of conditions of life for working people around the world.

Globalization on a capitalist basis inevitably means a convergence downward, as corporations shift capital and production around the world seeking the lowest-cost areas. China was once the benchmark for driving down living standards. Now the transnational companies are exploiting countries in South Asia, Africa and Latin America to drive wages and social conditions even lower.

The only alternative to this process of competitive devaluation of wages and living standards is to place the world economy on a new, socialist basis, through the unification of the international working class in a common struggle against the profit system.