Unsettling the Kim-Trump Summit: John Bolton’s “Libya Solution” for North Korea

The inevitable stop, start and stuttering of the Korean peace process was bound to manifest itself soon after the hugs, expansive smiles and sympathetic back rubs. Dates have been set – the Kim-Trump summit is slated to take place in Singapore on June 12, though there is much time for disruptive mischief to take place.

One field of possible disruption lies in air exercises between the US and South Korea known as Max Thunder. Such manoeuvres have been of particular interest to the DPRK, given their scale and possible use as leverage in talks.

The latest irritation was occasioned by claims in Pyongyang that the US had deployed B-52 Stratofortress bombers as part of the exercise despite denying that this would take place. This was construed, in the words of Leon V. Sigal, “as inconsistent with President Trump’s pledge at President Moon’s urging to move toward peace in Korea.”

The position against using such nuclear-capable assets had been outlined in Kim Jong Un’s 2018 New Year’s Day address. The South, he insisted, should “discontinue all the nuclear war drills they stage with outside forces,” a point reiterated in Rodong Sinmun, the Party newspaper, ten days later:

“If the South Korean authorities really want détente and peace, they should first stop all efforts to bringing in the US nuclear equipment and conduct exercises for nuclear warfare with foreign forces.”

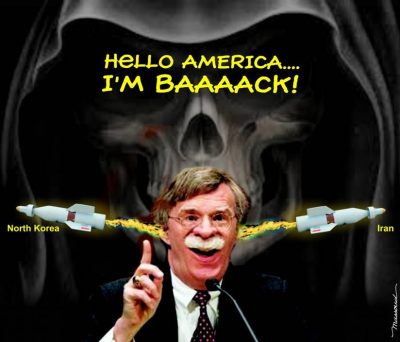

While these matters were unfolding, President Donald Trump’s national security advisor was being his injudicious self, doing his bit for global insecurity. Never a diplomat in the true sense of the term, John Bolton remains a traditional head kicker for empire, the rustler of discontent.

Bolton, history teacher incarnate, wants to impress upon the North Koreans certain jarring examples. A favourite of his is the so-called Libyan solution. How well that worked: the leadership of a country maligned but convinced in its international rehabilitation to abandon various weapons programs in the hope of shoring up security. More specifically, in 2003, Libya was convinced to undertake a process US diplomats and negotiators parrot with steam and enthusiasm: denuclearisation.

“We should insist that if this meeting is going to take place,” claimed Bolton on Radio Free Asia with characteristic smugness, “it will be similar to discussions we had with Libya 13 or 14 years ago: how to pack up their nuclear weapons program and take it toOak Ridge, Tennessee.”

The problem with this skewed interpretation lies in its false premise: that US threats, cajoling and sanctions has actually brought North Korea, tail between legs, to the diplomatic table. Being firm and threatening, according to Bolton, has been rewarding. This reading verges on the fantastic, ignoring three years of cautious, informal engagement. It also refuses to account for the fact that Pyongyang made firm moves in Washington’s direction after the insistence on firm preconditions was abandoned by Trump.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has also been rumbling on the issue of a firm line, suggesting that he, like Bolton, has a preference for the stick approach. Despite speaking about “warm” and “substantive” talks with Kim, he claims that any agreement with Pyongyang must have a “robust verification program” built into it.

The suggestion of the Libyan precedent was enough to sent Pyongyang into a state, given their developed fears about becoming the next casualty of unwarranted foreign intervention. Libya did denuclearise, thereby inflicting what could only be seen subsequently as a self-amputation. As missiles rained down upon Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, launched by the British, French and the US ostensibly for humanitarian reasons, a sense of terrible regret must have been felt. Soon, the mad colonel would be butchered, and his state torn asunder in a sectarian reckoning.

As the air assault was taking place, the North Korean foreign ministry identified the problem: the bargain between Libya and the western powers to surrender its nuclear weapons program was “an invasion tactic to disarm the country”. The intervention “is teaching the international community a grave lesson”.

The state news agency KNCA took note of Bolton’s remarks, issuing an official rebuff highlighting the status of the DPRK as a true, fully fledged nuclear weapon state: the “world knows too well that our country is neither Libya nor Iraq, which have met a miserable fate. It is absolutely absurd to dare compare the DPRK, a nuclear weapon state, to Libya, which had been at the initial stage of nuclear development.”

The DPRK’s vice foreign minister, Kim Kye Gwan, was unequivocal in warning.

“If the US is trying to drive us into a corner to force our unilateral nuclear abandonment, we will no longer be interested in such dialogue and cannot but reconsider our proceeding to the DPRK-US summit.”

Bolton received specific mention:

“We do not hide a feeling of repugnance toward him.”

The Trump White House preferred to give different signals. Sarah Huckabee Sanders is claiming that the president will be his own man on this, though Trump’s own reading of the “Libya model” has proven confusingly selective. In any case the leverage brought by US ultimatum to disarm without genuine concessions is hardly likely to gain traction. The response from Pyongyang will be simple: resume missile testing and further enlarge the arsenal.

*

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research. Email: [email protected]