Under Tillerson, Exxon Maintained Ties with Saudi Arabia, Despite Dismal Human Rights Record

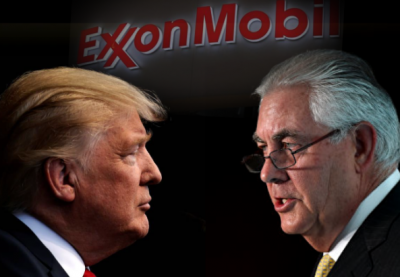

During his Secretary of State confirmation hearing, recently retired ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson came under questioningby Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) about his stance on Saudi Arabia’s awful human rights record, a country which contains the biggest oil reserves on the planet and is a long-time ally of the U.S.

While Tillerson offered mild criticism of Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women, LGBQT people, and others, several Senators found his response far from full-throated and said as much. A DeSmog investigation shows that Exxon has long been involved in Saudi Arabia’s oil and gas industry. Not only did the company, through its predecessor Standard Oil, help launch the industry there and co-owned the country’s first major export pipeline, but to this day it maintains deep business ties with Saudi Arabia and the industry in a variety of sectors, both there and in the U.S.

The U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations will vote on whether to confirm Tillerson on January 23, and Rubio’s vote one way or the other could make or break President-elect Donald Trump’s choice of Tillerson for Secretary of State. It appears human rights will play a central role in Rubio’s decision, which he has not yet made. However, Committee Chairman Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN) has threatened to bring Tillerson’s nomination to a full floor vote regardless of whether he passes in committee.

Corker took $6,000 in campaign contributions from Exxon during his 2006 electoral victory effort and another $10,000 for his 2012 re-election effort.

Exxon’s Saudi America

Exxon and Saudi Arabia have state-side projects too. Currently, Saudi state-owned company Saudi Arabia Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC) is working alongside Exxon through the company Gulf Coast Growth Ventures to permit and build a natural gas refinery facility along the Gulf of Mexico to manufacture plastics.

“Sites under consideration are in St. James and Ascension Parishes, Louisiana and San Patricio and Victoria Counties, Texas,” details the Gulf Coast Growth Ventures website. “We are very early in the process and have extensive studies and due diligence to perform before making a site selection decision among the four sites under consideration.”

Though not clarified on the company website, presumably that gas would be obtained via hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), given the horizontal drilling technique’s rampant use in Texas’ Eagle Ford, Barnett, and Permian Basin shale formations, as well as in Louisiana’s Haynesville Shale basin. The facility’s website only maintains that “feedstock for the facility will be acquired from domestic sources,” but industry publication Platts reported that much of that could be sourced from the Eagle Ford.

Meanwhile, a grassroots movement has arisen in opposition to the plant’s proposed site in Portland, Texas, calling itself Portland Citizens Unite. While Exxon has made appearances at city council meetings to advocate for the facility, it’s a hard sell. Portland’s city council passed a resolution on January 3 in opposition to the plant’s proposed locale.

Image Credit: City of Portland, Texas

Exxon and SABIC have also created a front group supportive of the project named We Are United for Growth, which showed up in green t-shirts (to represent giving the project a “green light”) at a recent Portland City Council meeting. SABIC says that it expects a final decision on whether to go ahead with the project by sometime during the second quarter of 2017.

Exxon in Saudi Arabia

Back in Saudi Arabia, Exxon also has a heavy footprint. In a 2016 company brochure, Exxon boasts of its close ties to the Saudi petrostate via three crucial petrochemical refining facilities.

“Today, ExxonMobil is one of the largest foreign investors in the Kingdom and also one of the largest private sector purchasers of Saudi Aramco crude oil,” reads the brochure. “Through our joint venture (JV) interests, we have participated in the petroleum refining and petrochemicals manufacturing industries in the Kingdom for over 35 years.”

Take the Saudi Yanbu Petrochemical Company (YANPET), a 50-50 joint venture between Exxon and SABIC, open in Saudi Arabia since the 1980s. This facility, similar to the Gulf Coast Growth Ventures one, creates the chemical compound ethylene, which is then used to manufacture plastics. YANPET is viewed as a worldwide model in the industry.

“Yanpet is a fully integrated plant, making it one of the largest and lowest-cost producers in the world,” writes Exxon. “It is recognized as a petrochemical industry global pacesetter.”

Saudi Aramco Mobil Refinery (SAMREF) is another of the major Exxon co-owned refineries in Saudi Arabia, this time with Saudi Aramco. Saudi Aramco owns and operates the Ghawar Field, the largest onshore oil field in the world, as well as the Safaniya Field, the world’s largest offshore oil field.

Opening in 1984, SAMREF situates itself as “one of the most sophisticated refineries in the Middle East, supplying products to a number of markets around the world,” according to Exxon. “SAMREF processes approximately 400,000 barrels per day of Arabian crude, and approximately half of its output is consumed domestically.”

And then there’s the Al-Jubail Petrochemical Company (KEMYA), a 50-50 SABIC-Exxon joint venture, which also manufactures plastics. On the supply side, Exxon owns a 49 percent stake in the Arabian Petroleum Supply Company (APSCO).

“APSCO operates its aviation fueling services in almost 21 national and international airports. APSCO is a long term supplier of aviation fuels to the national carrier, Saudi Arabian Airlines at several airports in the kingdom,” details its website. “Also, APSCOprovides bunkering and marine lubricants in several national and international ports on a 24 hours basis, utilizing a fleet of bunkering ships.

Exxon and Saudi Aramco are among the largest emitters of carbon in the world, according to a groundbreaking 2014 study by Richard Heede, completed for the Climate Accountability Institute.

Image Credit: CarbonMajors.org

“Often Been Reluctant”

The kindred bond between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia centering around fossil fuels is well-documented, becoming a central tenet of U.S. foreign policy after the famous handshake between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Saudi Arabia founder Abdulaziz Ibn Saud in 1945.

“We’ve often been reluctant to put as much pressure on states that we are dependent upon for oil, than in situations with states where we’re not dependent on oil,” said U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) during Tillerson’s January 12 confirmation hearing.

Would Rex Tillerson, given the corporate ties that bind him to Saudi Arabia and his long-standing support for the country, reverse course on this status quo as U.S. Secretary of State? That’s doubtful, to say the least.