The Battle for Lithium: The UK Supported the Coup in Bolivia to Gain Access to Its ‘White Gold’

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

After a coup in the South American country of Bolivia in November 2019, democratically elected president Evo Morales was forced to flee. Foreign Office documents obtained by Declassified show Britain saw the new military-backed regime, which killed 18 protesters, as an opportunity to open up Bolivia’s lithium deposits to UK firms.

On 10 November 2019, after the head of the army called for his resignation, Bolivia’s socialist president, Evo Morales, stepped down. It followed weeks of protests after the release of a report by the Organisation of American States (OAS) alleging irregularities in the election Morales had won the previous month.

Persecution from the new regime forced Morales to flee the country and an “interim president”, Jeanine Áñez, was installed. Widely condemned as a coup, resulting protests were met with lethal force.

Days after taking power, on 14 November 2019, the Áñez regime forced through Decree 4078 which gave immunity to the military for any actions taken in “the defence of society and maintenance of public order”.

The following day, on 15 November, Bolivian military forces shot and killed eight protesters in the city of Sacaba. On 21 November, regime forces killed another 10 protesters in the neighbourhood of Senkata just outside the capital La Paz.

Despite the deadly violence, which was condemned by human rights groups, the British embassy in La Paz moved quickly to support Bolivia’s new regime, Declassified can reveal from documents we have obtained.

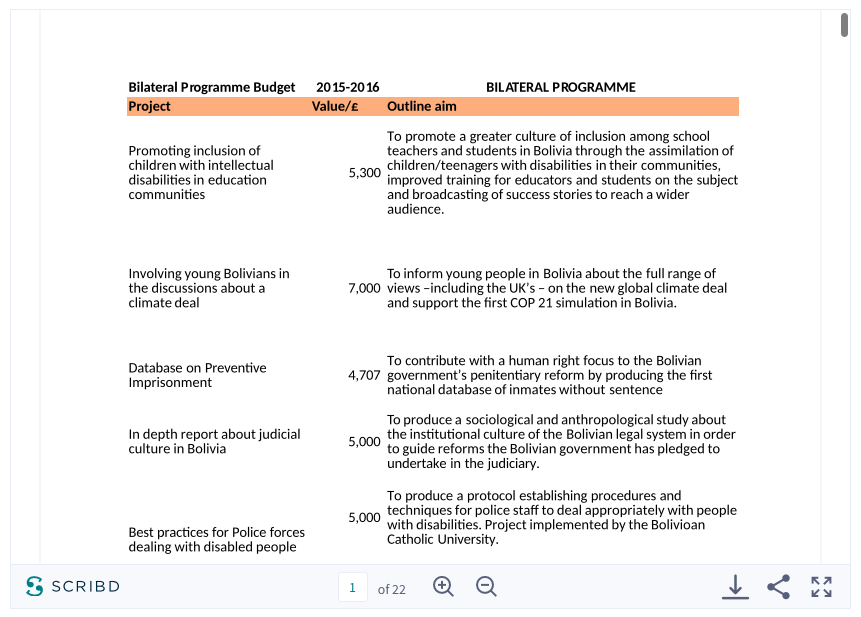

We have seen a project list for a Foreign Office programme in Bolivia called “Frontline Diplomatic Enabling Activity”, which the UK government describes as a “small pot of money that [embassies] receive and have authority over to spend on projects supporting [embassy] activity”.

The deposits

Bolivia has the world’s second-largest reserves of lithium, a metal that is used to make batteries and which has become increasingly important due to the burgeoning electric car industry.

The UK government has stated that lithium battery technology is a priority for its “industrial strategy”. In June 2019, it announced it was investing £23-million in “electric car battery development”.

The government has further noted: “It’s estimated that South America holds 54% of the world’s lithium resources, which are increasingly in demand to manufacture batteries for electric vehicles and energy diversification programmes.”

It added:

“The UK aims to have a thriving, sustainable battery industry, which would translate to a £2.7 billion opportunity … and our bilateral partnerships are essential to ensure this.”

In February 2019, Evo Morales’ government had chosen a Chinese consortium to be its strategic partner on a new $2.3-billion lithium project which would focus on production from the Coipasa and Pastos Grandes salars (salt flats under which the lithium is deposited).

But after the coup, the regime’s new minister for mining cast doubt on whether the deal would be honoured by the new government.

These particular salt flats were of interest to the UK embassy.

One project it co-funded from 2019-20 sought to “optimise Bolivia’s lithium exploration and production (in the Coipasa and Pastos Grandes salars) using British technology”.

After the coup, this project was quickly moved forward.

The abstract for the project was authorised by its main funder – the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) – on 25 November 2019, two weeks after the coup and days after the Senkata massacre.

The project gained full approval for funding of $100,000 weeks later, in mid-December 2019.

The IADB told Declassified: “The implementation of [grant] activities are conducted in close coordination with designated government authorities and their technical teams.” At that point its “close coordination” would have been with the Áñez regime.

Satellite Applications Catapult

The British embassy in La Paz provided £5,000 towards this lithium project in 2019-20, but the Foreign Office refused to tell Declassified if these funds were disbursed after the coup in November 2019.

The goal was to “design and implement a satellite data-based application that can optimise exploration and exploitation of large/best lithium sources in the Coipasa and Pastos Grandes salars in Bolivia”, the documents outlined.

The Foreign Office noted that the project was to be implemented by Satellite Applications Catapult, an Oxford-based organisation “helping organisations harness the power of satellite-based services”.

The company receives about a third of its funding from the UK government but it did not respond to Declassified’s questions about the Bolivia project.

However, we found that on 19 December 2019 – two days after the IABD gave final approval to the project – the UK Foreign Office transferred £33,220 to Satellite Applications Catapult, in a payment listed as “programme spend”.

The department refused to tell Declassified if this funding was for the lithium exploitation project in Bolivia. The IADB told us: “Coordination with the British Embassy has been particularly cooperative in search for synergies”.

A picture of the Coipasa salt flats in Bolivia, photographed by an Expedition 33 crew member on the International Space Station. (Photo: Nasa)

International seminar

Then, in March 2020, four months after the coup, the British embassy in La Paz partnered with the regime’s Ministry of Mining to organise an “international seminar” for more than 300 officials from the global extractives sector.

A British company, Watchman, was brought in by the UK embassy to give the keynote presentation and outline the “creative solutions” it had enacted in Africa to bring local communities onside with mining projects.

The Foreign Office documents note:

“Watchman UK and other consultancies are now in line to offer services in this important field to a number of Bolivia mining companies who wish to achieve win-win solutions to their controversies with indigenous inhabitants and towns located in the area of influence of their activities”.

Watchman is a risk management company set up in 2016 by Christopher Goodwin-Hudson, a nine-year veteran of the British Army who was later executive director of global security for the investment bank Goldman Sachs.

The company supports corporate clients “across the extractive, agribusiness and capital project sectors” who are having trouble operating because of local resistance. Watchman’s website carries the logo of the UK Foreign Office.

The firm’s associate director, Gabriel Carter, has held a number of senior roles in the private security industry and in 2012 founded an Afghanistan-focused security company that “supported numerous British and US development projects”.

Carter, also a veteran of risk management at Goldman Sachs, is a member of the Special Forces Club, an exclusive and secretive private members’ club for senior intelligence and special forces veterans in Knightsbridge, London.

Watchman did not respond to Declassified’s questions about the event and the UK Foreign Office refused to answer questions related to it.

Click here to read the document

UK Foreign Office documents from 2015-20 documenting a range of programmes run by the British embassy in Bolivia.

A long courtship

The quick moves of the British embassy on the lithium project followed years of trying to court Bolivia’s socialist government over the country’s reserves of the metal, the new documents show.

Morales had moved Bolivia away from the country’s traditional reliance on Western corporations since taking power in 2006. His government was widely praised for reducing poverty and increasing investment in schools, hospitals and infrastructure.

The Foreign Office notes that its “first engagement with the Bolivian Lithium Company”, known by its Spanish acronym YLB, was in 2017-18 when it paid £31,500 to organise a scientific UK mission. It focused on training the YLB on new technologies to explore and produce lithium in a “sustainable” way.

The documents note this project “allowed British organisations … to carry over projects on lithium in Bolivia with [Inter-American Development Bank] and [UK government] funding in the following years”.

The UK government noted:

“Relationship with the Bolivian Lithium Company might also prove relevant as Bolivia becomes a supplier of lithium (a critical material) to the UK”, and referenced its “effort to connect Bolivia, Chile and Argentina (ie the Lithium Triangle) with the London Metal Exchange”.

The following year’s programme notes that “stronger links” developed between the YLB and the British embassy in Bolivia.

The documents also outline how in April 2019, the British embassy in Buenos Aires, Argentina, hosted a “high-level technical meeting” with the mining and lithium authorities of Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, as well as senior representatives of the London Metal Exchange.

Those three countries together share ownership of the “lithium triangle”, the region of the Andes rich in lithium reserves. At the time Argentina and Chile had right-wing governments friendly with the UK.

Also in attendance was Bolivia’s vice-minister of lithium and the chief executive of YLB. “The project from the British Embassy in Bolivia … consisted in securing and facilitating the presence of the Bolivian authorities in the meeting”, the Foreign Office documents note.

It added that, after the meeting, the Bolivian government was now “aware of the relevance of the London Metal Exchange” and particularly “its interest to establish a lithium standard” which was to be based upon the lithium triangle production. Such standards serve “to promote understanding and communication between metal producers and users”.

The following sections in this passage are redacted under two exemptions related to “international relations” and “commercial interests”. These are the only redactions made on the programme documentation for the five years of operations seen by Declassified.

The London Metal Exchange, the world centre for industrial metals trading. (Photo: UK government)

Darktrace

There is further evidence Britain was always priming the country for a change in government. In the year before the coup, the British embassy was promoting the UK cyber sector, bringing a company to Bolivia founded by the UK intelligence community, and with close links to America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

In 2009, Morales had expelled a US diplomat who he claimed was a CIA asset heading an operation to infiltrate Bolivia’s state-owned oil company.

Eight months before the coup, the UK embassy spent more than £4,500 organising a “major event” in Laz Paz on cybersecurity for financial institutions, attended by 150 executives and senior officials from the Bolivian financial sector, according to the Foreign Office documents.

Delivered in coordination with the Bolivian Stock Exchange, Bolivian banks were said to “now be acquiring specialised services to protect their systems from cybercrime”. Further, the bankers were now aware that fighting cybercrime had to be “based upon adequate and state-of-the-art technology”.

Presentations were delivered by British company Darktrace, a cybersecurity firm set up by Britain’s domestic security service, MI5, and its signals intelligence agency, GCHQ. The company was incorporatedthe day after the first of whistle-blower Edward Snowden’s exposures was published in The Guardian.

Since its founding, Darktrace has hired personnel from the US intelligence community, including directlyfrom the CIA and the National Security Agency, where Snowden used to work.

Recruits from the CIA

Alan Wade, who sits on Darktrace’s advisory council, is a 35-year veteran of the CIA and its former chief information officer.

Darktrace also recruited Marcus Fowler, a former US Marine and 15-year veteran of the CIA, as its “director of strategic threat”. At the CIA, Fowler worked on “developing global cyber operations and technical strategies” and “conducted nearly weekly briefings for senior US officials”, he says.

In July 2013, Evo Morales’ presidential plane was grounded in Austria after US intelligence agencies suspected it had Snowden on board.

Morales blamed the US and other international actors for the November 2019 coup. “It was a national and international coup d’état,” he said soon after. “Industrialised countries don’t want competition.” He added: “I’m absolutely convinced it’s a coup against lithium.”

The WikiLeaks diplomatic cables show that the US embassy in La Paz worked closely with the political opposition in Bolivia to remove the Morales government after it took power in 2006.

Morales expelled the US Drug Enforcement Agency in 2008 and the US Agency for International Development in 2013, accusing them of “conspiring” against his government.

For the March 2019 event, the UK embassy also brought an expert from the London-based think tank Chatham House, whose co-president is Eliza Manningham-Buller, a former director-general of MI5.

Its funders include the US State Department, UK Foreign Office, the British Army, and the oil companies BP and Chevron.

After the event, Britain’s Foreign Office noted that “several companies in the field [are] now being hired and consulted”. It is not known if Darktrace was one of them.

The embassy kept up the engagement soon after. “New dialogue with the Bolivian government on cyber”, notes the Foreign Office in its 2019-2020 programme. It is unclear if this referred to the coup regime.

‘Important input’

The day after the Bolivian election on 20 October 2019, the Washington-based Organisation of American States – the grouping of countries in North and South America – released a report on the vote which Morales had marginally won. It cited “an inexplicable change” that “drastically modifies the fate of the election”.

It also raised doubts about the fairness of the vote and fuelled a chain of events that led to the November coup.

However, a subsequent study by independent researchers using data obtained by The New York Times from the Bolivian electoral authorities found that the OAS statistical analysis was flawed.

Its conclusion that Morales’ share of the vote jumped inexplicably in the final ballots relied on incorrect data and inappropriate statistical techniques, the researchers found.

Declassified can now reveal that the British embassy provided data for the OAS’s discredited report.

The British embassy spent £8,000 putting together an alliance of civil society organisations which “coordinated an operation for citizens’ observation of the elections in 2019”.

This alliance carried out a survey on voting intentions before the elections, which “was an important input for the OAS mission report, which identified irregularities in the process”, the Foreign Office notes.

The OAS failed to respond to Declassified’s questions about the UK embassy’s role in its discredited report and the Foreign Office refused to answer any questions about it.

The British embassy’s projects to prepare for the election went even further. In February 2019, it spent £9,981 to bring the Thomson Reuters Foundation to the country to train 30 Bolivian journalists on “verification techniques and pre-planning an election on coverage that is balanced, accurate and free of polarisation”.

The Foundation said that “ahead of the elections in Bolivia” it was teaching “practical skills and tools to recognise fake news and attempts to influence the electorate with false information”.

Declassified previously revealed how the British government is using journalism as an influencing tool in Latin America. Also recently revealed was that the British government secretly funded Reuters in the 1960s and 1970s at the behest of an anti-Soviet propaganda unit linked to British intelligence.

‘Marxist solidarity’

Days after the November coup in Bolivia, the UK Foreign Office released a statement saying:

“The United Kingdom congratulates Jeanine Áñez on taking on her new responsibilities as interim President of Bolivia.” It added: “We welcome Ms Áñez’ appointment and her declared intention to hold elections soon.”

Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab stated:

“We hope that the current crisis in Bolivia can now be resolved swiftly, peacefully and in a democratic way. The Bolivian people deserve to have the opportunity to vote in free and fair elections.”

Then Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn offered a completely different view, saying: “I condemn this coup against the Bolivian people and stand with them for democracy, social justice and independence.”

Raab proceeded to attack Corbyn, quote-tweeting him and stating:

“Unbelievable. The Organisation of American States refused to certify the Bolivian election because of systemic flaws. The people are protesting and striking on an unprecedented scale. But @jeremycorbyn puts Marxist solidarity ahead of democracy.”

But Raab and the Foreign Office made no further comments as the new regime’s forces carried out the Sacaba and Senkata massacres the following week.

In March 2020, four months after Morales was overthrown, the new regime was organising a series of new initiatives “with the UK as a strategic partner”, the documents note.

That same month, Britain’s ambassador during the coup, Jeff Glekin, offered a glimpse of the UK interests involved in backing the new regime.

Glekin spoke to the Bolivian media about British Week, which was bringing 12 British companies to the country for the first time.

“Many are looking for new markets in the world and Bolivia can be an opportunity to grow,” he said. “Due to the political changes in Bolivia, a more open environment for foreign investment is perceived and I believe that this will open new doors to companies that want to share their technology, their products and make alliances with different companies.”

Glekin, who remains in post, added:

“We are working with the Santa Cruz Mayor’s Office … and we invite Santa Cruz corporations to participate in the event.”

In the documents seen by Declassified, a disproportionately high number of UK embassy projects have focused on the eastern city of Santa Cruz, which was the centre of opposition to Evo Morales’ government.

Glekin continued:

“The previous government was not very in favour of foreign investment. So, with the changes that we are going to see, it will be easier to enter the market and do business. The companies to come are from different parts of Great Britain and from various sectors. They are modern firms that are doing innovative things and want to enter the market and share their services and products in Bolivia.”

Glekin added:

“The demand for lithium is growing and Bolivia must take advantage of that opportunity.”

When new elections took place in October 2020, Evo Morales’ Movimiento al Socialismo won 55% of the votes against six rivals on the ballot, easily avoiding the need for a runoff. The runner-up was former President Carlos Mesa with just under 29%.

A Foreign Office spokesperson told Declassified:

“Presidential elections held in Bolivia in October 2020 were free and fair. There was no coup. The UK has a strong and constructive relationship with current and former Bolivian administrations.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Matt Kennard is head of investigations at Declassified UK, an investigative journalism organisation that covers the UK’s role in the world.

Featured image is from People’s Dispatch