From Land to Logistics: UAE’s Growing Power in the Global Food System

“We are progressively moving forward in the disruption of food systems to be able to grow anything anywhere regardless of climate and environment.” – UAE government, 2023[1]

“Logistics is where the Emirates’ commercial and strategic ambitions overlap.” – Financial Times, 2024[2]

While all eyes are on Gaza, further south in Sudan another atrocious conflict is leading to mass starvation.

The fighting that broke out in April 2023 pits a militant faction called the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) against rival state militias. Both are vying for control of the country and its rich mineral and agricultural resources. More than 14,000 people have been killed, another 33,000 have been injured, some ten million have been displaced and a situation of generalised famine is setting in.[3] The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is alleged to be arming the RSF. Why? In part, observers say, to protect shipments of gold, livestock and crops.[4] Of course, the UAE rebuffs the claim, but evidence speaks otherwise.

In the pursuit of its own food security, the UAE, like other Gulf states, has been getting control of land to develop farm operations in Sudan. Right now, two Emirati firms –International Holding Company (IHC), the country’s largest listed corporation, and Jenaan – are farming over 50,000 hectares there. In 2022, a deal was signed between IHC and the DAL group – owned by one of Sudan’s wealthiest tycoons – to develop an additional 162,000 ha of farmland in Abu Hamad, in the north. This massive farm project, backed by the UAE government, will connect to a brand-new port on the coast of Sudan to be built and operated by the Abu Dhabi Ports Group. The economic stakes around this project are mammoth. But so are the political ones. The current port of Sudan, which the project will completely bypass, is run by the Sudanese government.

Despite being a tremendously wealthy country, due to its massive oil and gas reserves, the UAE is food insecure and depends on other territories for its food supply. This is not new. The UAE has been leaning on other countries for food for decades, as it grows into a financial powerhouse with a predominantly immigrant population. Ever since the food price crisis of 2007-2008, followed by Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, all of which disrupted supplies for Gulf States, the Emirates have amassed some 960,000 hectares of farms overseas. Now, though, these global farm operations are increasingly being tied to the UAE through a tightly controlled network of ports and logistics platforms, all of which are entwined with security concerns.[5]

Outsourced food production does require logistical prowess to move goods from overseas farms to local consumers, and the UAE, with some of the world’s top port companies, aviation providers and warehouse operators, has the capacity for it. But such a logistical empire brings with it a security dimension, which, in the case of the UAE, overlaps with geopolitical and military interests. This can reinforce unequal power relations or worse, as can be seen in Africa. Moreover, the UAE’s long-term ambition is not only to become food self-sufficient, but also to become a central hub in the world’s changing agrifood trade system. This means becoming a critical shipping or airfreight point between Asia, Africa and Europe, with the technological capacity to move food safely and quickly. Given the UAE’s immense spending power and regulatory laxity – think of tax havens and free zones – towards international investors, it may just succeed.

The growing financial, corporate and political power of the UAE in the global food system needs to be held to account, not least because of its direct implications for local communities.

UAE Agrifood Investors

Food security is a priority agenda of the UAE government since the global food crisis of 2007, when it learned that markets – and therefore its unfathomable oil wealth – were not dependable. It went into high gear to change this, starting off with foreign investment, including a string of controversial land and water grabs.[6] Twenty years later, in 2018, the UAE launched a food security strategy which proposes a mix of overseas and domestic investment.[7] Its aim was to see the UAE in the top ten of the global food security index by 2021 (in reality, it was number 35) and number one by 2051. The plan not only involves more overseas farms but also a ramp up in domestic food production to cut the UAE’s reliance on food imports from the current 90%, at a cost of US$14bn a year, to 50%.[8]

The key actors in this scheme are a mix of public and private corporations, often linked to the royal family and state foreign policy. The most powerful is surely the Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company or ADQ, one of the country’s sovereign wealth funds.[9] Several others are part of the industrial elite of the UAE. The table below highlights notable players in overseas agrifood investment and their larger interests in infrastructure and geopolitics. As the table reveals, these investments are new, interlinked and growing.

Table 1: UAE overseas agrifood investors with links to logistics & security

Click here to read the full sheet

The logistics piece of this food system strategy revolves mainly around ports and processing. Two Emirati companies, Dubai Ports World and Abu Dhabi Ports Group, are among the world’s top seaport operators. They are building an immense network of terminals around the planet that link back to the main ports of the UAE.[10] Of these, Jebel Ali Port, run by the DP World, is the biggest and newest. The government aims to turn Jebel Ali into a vital transshipment port for global food trade in the years ahead.

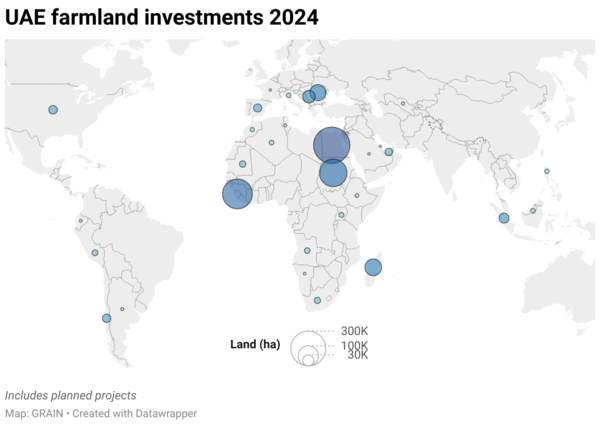

Underlying the UAE’s food security strategy is a growing concentration of farmland in the hands of a few key players. The data on land holdings, whether through ownership or lease, has been compiled below, into a separate table and map. Many of these land holdings involve privileged access to water sources as well.[11]

Table 2: Farmland holdings by UAE companies in 2024

Click here to read the full sheet

Regional Power Dynamics in Africa

While UAE agribusiness investments span the world, a few countries in North and East Africa are key targets of geopolitically driven initiatives. Take Egypt. Two government-owned Emirati groups – Al Dahra and Jenaan – are particularly invested in agricultural production in Egypt. Al Dahra operates more than 260,000 ha there, producing cereals and fruits, while Jenaan has holdings of more than 52,000 ha of fruits, dairy farms and fodder crops. Another important investor is International Holding Company (IHC), Abu Dhabi’s largest listed company, chaired by Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Emir’s brother and the country’s National Security Advisor. IHC owns Al Hashemaya, with over 4,000 ha of farmland in Egypt.

UAE and Egypt have good political but very unequal economic relations. In 2024, Al Dahra boasted that for the last three consecutive years it has been “the largest producer of Egypt’s most strategic crop: wheat.” The UAE government is also financing Egypt’s own wheat imports, showing a high level of dependency between the two. Given the strategic importance of Emirati control over ports on the Red Sea and Suez Canal, and its new concession along Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, this dependency may only grow.[12]

It’s another story in the Horn of Africa. In 2018, Djibouti kicked DP World out of the Doraleh Container Terminal, a port that is crucial for moving goods in and out of landlocked Ethiopia. Djibouti claimed that the agreement they had unfairly benefited DP World, so it cancelled the deal, nationalised the port and gave China a share instead. DP World then moved to Berbera in Somaliland, where in exchange for being allowed to run a port it promised to build a road to Hargeira, the capital, and to the border of Ethiopia. On top of this, the UAE is ruthlessly suing Djibouti in court for cancelling their deal and raking in enormous fees.[13]

Further south, UAE food security investors are carving space for themselves in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. The government of Uganda is reportedly taking advantage of the war in Sudan to become a new hub for UAE investment.[14] “As Uganda is primarily an agricultural country, it can meet the UAE’s food needs and acquire the UAE’s technology to help add value to Uganda’s agricultural produce,” the Foreign Minister recently put it.[15] President Museveni even signed a deal allowing the UAE to build one of the world’s only agricultural free zones. It is a 2,500 ha park that will serve to process and ship food (sugar, tea, beef and maize are on the table) from Uganda to the UAE. He also granted 7,000 ha to Al Rawabi to develop livestock production. Recently, a member of the UAE royal family who is building a major oil refinery in Hoima, announced that he will provide seven cargo planes and a cold storage centre in Entebbe to boost Uganda food exports. Uganda is already scarred by conflicts that emerge around land granted to foreign investors, so the UAE is reportedly treading cautiously. Still, Museveni is determined. He recently gave the UAE majority rights over Uganda’s information and communication technology backbone, which should raise concerns about national security.[16]

In Tanzania, similar projects have caused an uproar. While the violent expulsion of 70,000 Maasai to make way for a game reserve for UAE royals is ongoing, the government has now signed a deal with DP World, giving it the rights to upgrade and exclusively operate Dar es Salaam port for 30 years. This raised enormous opposition from civil society, political parties and even the courts for unfairly benefiting the UAE and trampling national sovereignty.[17] There is no doubt that this facility will boost the leverage of Emirati agri-investors in the region.

UAE companies have launched new agribusiness projects in other African countries as well. The UAE and Kenya just signed a free trade deal, and now ADQ has committed to invest up to $500mn there, including in food production. In Zambia, the UAE and other Gulf investors are looking at acquiring farmland to produce grains, sugar, beans and seeds, as well as dairy and goat farming.[18] In Zimbabwe, UAE companies are producing tobacco, macadamia nuts, bananas, avocados, citrus and berries for export, with further expansion contingent on gaining access to more farmland.[19]

Outsourcing Production in Asia

Significant new opportunities are opening up for UAE agri-investors in Asia, as well. Some Emirati companies, like Elite Agro and Unifrutti, are already vested in the traditional model of building international agribusiness operations in place likes Indonesia and the Philippines – not directly linked to logistics or security agendas. In Indonesia, Elite Agro was granted rights to 18,000 ha in Central Kalimantan a few years ago. The most recent news is that they are considering investing in the government’s food estate programme.[20] Information on this is scant, however, as they want to avoid protests.[21] In the Philippines, Unifrutti – a major fruit producer for the UAE and international markets – produces bananas on 1,700 ha of plantations.[22]

In India, an important new initiative is taking off. In 2022, the governments of the UAE and India agreed to set up a “food corridor” between the two countries. It involves creating a potentially large number of “food parks” in India, starting in Gujarat, where production will be centralised and then processed for shipment to the UAE. The food parks are free zones, where laws like India’s Essential Commodities Act – which regulates food trade in the public interest – will not apply. The government of the UAE has committed $2bn to the project, while a consortium of UAE companies are ploughing in another $7bn to develop logistics, including top-down processes to meet UAE food safety standards. The initial crops being produced are mangoes, chillis, onions, rice and okra.[23]

The potential scope of this project is far reaching. While it stems from earlier plans developed solely between India and the UAE, it has been launched under the umbrella of the quadrilateral India-Israel-UAE-USA alliance, which grew of out of the Abraham Accords. In essence, India is providing the land and farm labour, Israel and the US are providing the technology and the UAE is providing the market, with Jebel Ali as the key port. If it does take off, we could see it serving the UAE’s longer term agenda of becoming a core hub for global food trade between Asia, Europe and Africa.[24] Already this year, the UAE is planning to bring farm workers over from India, to help the Emirates produce more of their own food domestically (especially in vertical farms) and cut imports. The plan is to bring over 20,000 workers at first, and 200,000 over time.[25]

In Pakistan, the UAE is once again looking to set up farm operations. Earlier attempts during the food and financial crisis of 2008 failed. This time, with the war in Ukraine, things may be different. Things started moving in June 2023 after the High Court of Lahore nixed the army’s plan to hand over 400,000 ha of land for corporate farming in Punjab to China. Instead, a 50-year concession at Karachi Port, as well as three logistics agreements, were signed with AD Ports Group. Two months later, Pakistan’s parliament adopted a bill establishing a Special Investment Facilitation Council to seek investment from Gulf states, particularly in food and agriculture. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are both being solicited, with Al Dahra showing a keen interest from the UAE. The proposal is to set up corporate farms on 40,000 ha by 2030, starting with 2,000 in Punjab. Already in December 2023, the UAE signed US$25bn worth of deals with Pakistan, including in agriculture, potentially starting off with halal meat and date palm production for export to the UAE.

It is important to note that in a lot of this deal making, political strings are pulled so that UAE companies get special dispensations. For example, in March 2024, India had a ban on onion exports because of rising prices at home and its huge importance to the Indian people. The UAE got an exception to the ban so that it could export onions from India regardless. Same in Pakistan. The new investment law reportedly provides a “sovereign guarantee” that UAE investors will be able to continue their food security projects despite any change of leadership in Pakistan. Similarly, when the UAE government bought 45% of the Louis Dreyfus Company in 2020, a side agreement was signed guaranteeing food shipments to UAE in times of supply crises.[26]

Global Patterns

A similar pattern is at work in Europe and the Americas. UAE interests have been pursuing a close relation with the government of Serbia that combines farmland investing and arms sales. In 2013, the UAE Development Fund provided an initial US$400 million loan for Serbian agriculture. Soon after, Al Dahra bought eight Serbian farming companies while Elite Agro also started building its own operations there. In 2018, Al Dahra took over the agricultural assets of PKB Korporacija, the former Yugoslavia’s largest farm, despite the opposition of the Serbian military. How is that? The UAE government has a fixer in Serbia facilitating contracts to develop defence systems as well as arms sales to UAE (which end up in the hands of militants fighting in Syria and Yemen).[27]

In the US, the UAE has been investing, alongside Saudi Arabia, in farm production in water-stressed Arizona for several years now. Al Dahra has over 12,000 ha there to grow alfalfa, which is shipped back to the UAE as hay. Communities in Arizona are up in arms about how these investors have been granted unlimited rights to local water supplies, while ordinary people suffer epic and worsening droughts.[28] To their stupefaction, they’ve learned that the Arizona state pension fund is directly involved as an investor in these projects.[29]

In Latin America, UAE is carefully expanding it footprint. Emirati investors are producing poultry in Brazil and fruit in Chile and Peru. Explorations are ongoing to find farm deals in Mexico and Colombia, with free trade agreements on the offer and business coalitions being set up. UAE has even just become an observer to the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture, where it plans to help shape the region’s food systems.[30]

Taken as a whole, the UAE is racing ahead to consolidate global farming operations (with secure land and water access, and high food safety standards) connected to sophisticated transport logistics (air, road and sea). Its ambitions are not only to produce its own food but to serve as a global trade hub. The new US$150 million project to expand Jebel Ali port is precisely for this purpose.[31] But even smaller ports like Dubai Creek and Deira play an important role in international rice trade with India and Iran. Thanks to a web of global free trade and tax agreements, traders in the UAE can import and re-export products quickly to other markets, without duties coming into the picture.[32] This combination of logistical might and regulatory freedom make the UAE an attractive transshipment route.

Big Ambitions, Deep Concerns

The UAE’s deepening control over international farmland and water resources, in tight coordination with its logistical power and security agendas, is worrisome. The fact that the government wants to shore up food security through domestic production could be a good turn, if they were able to develop truly sustainable systems. While they’re at it, they should address the country’s abysmal record on food waste, too.[33] But taking over land and water resources – especially without local communities’ explicit consent or in areas where hunger is rife – should simply not be allowed.

Unfortunately, the UAE’s overseas farm ambitions are tightly intertwined with geopolitical and financial incentives. And things could get worse. On the one hand, there is a longstanding rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the UAE that pushes both down this path in parallel and acts as an accelerant.[34] On the other hand, the increasing pressure of climate change is being turned into a cover for Gulf States engaged in outsourced food production. The UAE, an increasing power in international climate discussions, has embraced carbon offsetting as a key path to greenwash its own formidable climate footprint.[35] Carbon deals are being made right and left, especially in Africa, to keep forests intact or grow trees on rural territories so that credits can be sold to global polluters. And the new business of carbon farming can both help to fund the UAE’s overseas farms and offset its companies emissions.[36] This new rush for carbon land deals will rob local communities of their food systems and local livelihoods in yet new and pernicious ways.

The mass starvation being waged in Sudan should be a terrible reminder of why agricultural land deals meshed with geopolitical agendas must end.[37] It’s time to call the UAE, and its allies, to account.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Spread the Truth, Refer a Friend to Global Research

Notes

[1] UAE, https://www.moccae.gov.ae/en/knowledge-and-statistics/food-safety.aspx

[2] David Pilling et al, https://www.ft.com/content/388e1690-223f-41a8-a5f2-0c971dbfe6f0

[3] Julian Borger, “‘We need the world to wake up’: Sudan facing world’s deadliest famine in 40 years”, The Guardian, 17 June 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/17/we-need-the-world-to-wake-up-sudan-facing-worlds-deadliest-famine-in-40-years. For more details, see the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification’s latest alert on Sudan: https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1156903/?iso3=SDN

[4] The allegation that UAE is arming the Rapid Support Forces has been established by UN expert groups, Human Rights Watch and several governments, although the UAE denies it. The link to gold and food shipments has been advanced by numerous observers. See for example, “Sudan fighting threatens $50bn Gulf investments”, Middle East Monitor, 24 May 2023, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20230524-sudan-fighting-threatens-50bn-gulf-investments/

[5] We’re indebted to Christian Henderson and Rafeef Ziadah for making these connections clear. See “Logistics of the neoliberal food regime: circulation, corporate food security and the United Arab Emirates”, New Political Economy, 5 Dec 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13563467.2022.2149721. See also Uusimiir, “One port, one node: The Emirati geostrategic road to Africa”, Somali Forum, Jun 2023, https://community.somaliforum.com/t/one-port-one-node-the-emirati-geostrategic-road-to-africa/2100

[6] A compilation of news reports is available here: https://farmlandgrab.org/cat/47

[8] By comparison, Saudi Arabia is at 75%. See https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-08/uae-to-grow-more-food-in-the-desert-as-pandemic-disrupts-imports and https://fas.usda.gov/data/opportunities-us-agricultural-exports-uae

[9] For a deep dive into sovereign wealth funds and their investments in global agribusiness, see GRAIN, “Will sovereign wealth funds mean less food sovereignty?”, 2023, https://grain.org/e/6976.

[10] Henderson and Ziadah, op cit.

[11] See GRAIN, “Squeezing communities dry: water grabbing by the global food industry”, 21 Sep 2023, https://grain.org/e/7039.

[12] Patrick Werr and Karla Strohecker, “Egypt announces $35 billion UAE investment on Mediterranean coast”, Reuters, 23 Feb 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/egypt-announces-multi-billion-uae-investment-boost-forex-2024-02-23/

[13] Nosmot Gbadamosi, “The UAE faces pushback on African investments”, Foreign Policy, 8 Nov 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/08/the-uae-faces-pushback-on-african-investments/

[14] “Museveni lends land in bid to make Uganda a regional hub for Emirati trade”, African Intelligence, 10 October 2023, https://www.africaintelligence.com/eastern-africa-and-the-horn/2023/10/10/museveni-lends-land-in-bid-to-make-uganda-a-regional-hub-for-emirati-trade,110064090-art

[15] Gulf Today, “UAE, Kenya finalise Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement”, 23 Feb 2024, https://www.gulftoday.ae/business/2024/02/23/uae-kenya-finalise-comprehensive-economic-partnership-agreement

[16] See Giles Muhami, “Museveni: Give UAE investor 60% of Uganda Telecom, ICT backbone for $250m”, Chimpreports, 27 Feb 2024, https://chimpreports.com/museveni-give-uae-investor-60-of-uganda-telecom-ict-backbone-for-250m/ and George Asiimwe, “UAE prince to provide 7 cargo planes for Uganda’s agro exports”, Chimpreports, 17 Jun 2024, https://chimpreports.com/uae-prince-to-provide-7-cargo-planes-for-ugandas-agro-exports/. See also EIG website: https://www.eastafricangroups.com/sectors and Emirates News Agency, “Ugandan FM: Agriculture-tech synergy to help expand ties with UAE”, 24 Feb 2024, https://www.zawya.com/en/economy/gcc/ugandan-fm-agriculture-tech-synergy-to-help-expand-ties-with-uae-ysun9oog

[17] Beverly Ochieng, “DP World in Tanzania: The UAE firm taking over Africa’s ports”, BBC, 23 Oct 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-67199490

[18] Sarah Townsend, “Seeds of Gulf-Africa agribusiness”, Cairo Review of Global Affairs, 11 March 2020, https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/seeds-of-gulf-africa-agribusiness/

[19] Elite Agro CEO speaking on 24 Feb 2024: https://x.com/Lancell_Rugg1/status/1758115514893631671

[20] Jayanty Nada Shofa , “UAE’s Elite Agro mulls investing in food estate, minister says”, 2 Feb 2024, https://jakartaglobe.id/business/uaes-elite-agro-mulls-investing-in-food-estate-minister-says

[21] “Government agrees to develop agriculture farm and plantation with Elite Agro UAE LLC”, Sampit Prokal, 18 Oct 2023, https://www.farmlandgrab.org/29419

[22] Unifrutti, “Sustainability report 2022”, https://unifruttigroup.com/sito/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Unifrutti-Group-2022-Sustainability-Report.pdf

[23] Michaël Tanchum, “The India-Middle East Food Corridor: How the UAE, Israel, and India are forging a new inter-regional supply chain”, Middle East Institute, 27 Jul 2022, https://www.mei.edu/publications/india-middle-east-food-corridor-how-uae-israel-and-india-are-forging-new-inter and “APEDA facilitates visits of farmer producer organisations (FPOs) to UAE to unlock their export potential”, 7 Mar 2024, https://agriculturepost.com/agribusiness/farmer-producer-organisations/apeda-facilitates-visits-of-farmer-producer-organisations-fpos-to-uae-to-unlock-their-export-potential/

[24] See, for example, the KEZAD project: https://adfoodhub.com/ and Gulf Business, “Dubai breaks ground on mega $150m Agri Terminals facility”, 24 Feb 2024, https://gulfbusiness.com/dubai-breaks-ground-on-agri-terminals-facility/

[25] Subramani Ra Mancombu, “UAE to recruit agri workers to increase farm production, cut imports”, The Hindu Businessline, 2 Jan 2024, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/uae-to-recruit-agri-workers-to-increase-farm-production-cut-imports/article67698132.ece

[26] ADQ, “ADQ enters agreement to acquire stake in Louis Dreyfus Company”, 11 Nov 2020, https://www.adq.ae/newsroom/adq-enters-agreement-to-acquire-stake-in-louis-dreyfus-company/

[27] Vuk Vuksanovic, “Serbia’s best friend in the Arab world: The UAE”, Middle East Institute, 9 Jul 2021, https://www.mei.edu/publications/serbias-best-friend-arab-world-uae

[28] Rob O’Dell and Ian James, “Arizona provides sweet deal to Saudi farm to pump water from Phoenix’s backup supply”, Arizona Republic, 9 Jun 2022, https://eu.azcentral.com/in-depth/news/local/arizona-environment/2022/06/09/arizona-gives-sweet-deal-saudi-farm-pumping-water-state-land/8225377002/

[29] An important film has just been released about this: https://revealnews.org/the-grab/

[30] See Reuters, “Abu Dhabi-owned Unifrutti eyes further Latam growth after fresh acquisitions”, 9 Mar 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/abu-dhabi-owned-unifrutti-eyes-further-latam-growth-after-fresh-acquisitions-2024-03-09/; ANI, “UAE invited to join Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture as observer country”, 14 Jun 2024, https://www.aninews.in/news/world/middle-east/uae-invited-to-join-inter-american-institute-for-cooperation-on-agriculture-as-observer-country20240614150629/

[31] See Gulf Today, “Jebel Ali to get new Agri Terminals”, 28 Mar 2024, https://www.gulftoday.ae/business/2024/03/28/jebel-ali-to-get-new-agri-terminals.

[32] US Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, “United Arab Emirates: Grain and feed annual”, 5 Apr 2023, https://fas.usda.gov/data/united-arab-emirates-grain-and-feed-annual-6

[33] The UAE ranks among the top nations for per capita waste generation. Nearly 40% of the food prepared every day there is wasted, jumping to 60% during Ramadan. https://dcce.ae/press_releases/our-food-is-damaging-the-environment/

[34] See, for instance, Stratfor, “The Saudi-UAE regional rivalry intensifies”, 27 Jul 2023, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/saudi-uae-regional-rivalry-intensifies

[35] GRAIN, “The Davos-isation of the climate COP”, 15 Feb 2024, https://grain.org/e/7104

[36] GRAIN, “From land grab to soil grab – the new business of carbon farming”, 24 Feb 2022, https://grain.org/e/6804

[37] Abubakr Omer Dafallah Omer, “Seeds of sovereignty: reshaping Sudan’s food system”, Nov 2023, Siyada, https://en.siyada.org/abubakr-omer/research-and-publications/new-study-seeds-of-sovereignty-reshaping-sudans-food-system/

Featured image: DP World Facebook account