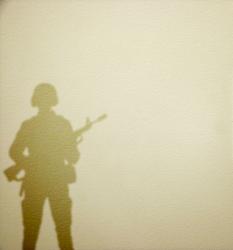

U.S. Is Said to Expand Secret Military Acts in Mideast Region

WASHINGTON — The top American commander in the Middle East has ordered a broad expansion of clandestine military activity in an effort to disrupt militant groups or counter threats in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and other countries in the region, according to defense officials and military documents.

The secret directive, signed in September by Gen. David H. Petraeus, authorizes the sending of American Special Operations troops to both friendly and hostile nations in the Middle East, Central Asia and the Horn of Africa to gather intelligence and build ties with local forces. Officials said the order also permits reconnaissance that could pave the way for possible military strikes in Iran if tensions over its nuclear ambitions escalate.

While the Bush administration had approved some clandestine military activities far from designated war zones, the new order is intended to make such efforts more systematic and long term, officials said. Its goals are to build networks that could “penetrate, disrupt, defeat or destroy” Al Qaeda and other militant groups, as well as to “prepare the environment” for future attacks by American or local military forces, the document said. The order, however, does not appear to authorize offensive strikes in any specific countries.

In broadening its secret activities, the United States military has also sought in recent years to break its dependence on the Central Intelligence Agency and other spy agencies for information in countries without a significant American troop presence.

General Petraeus’s order is meant for small teams of American troops to fill intelligence gaps about terror organizations and other threats in the Middle East and beyond, especially emerging groups plotting attacks against the United States.

But some Pentagon officials worry that the expanded role carries risks. The authorized activities could strain relationships with friendly governments like Saudi Arabia or Yemen — which might allow the operations but be loath to acknowledge their cooperation — or incite the anger of hostile nations like Iran and Syria. Many in the military are also concerned that as American troops assume roles far from traditional combat, they would be at risk of being treated as spies if captured and denied the Geneva Convention protections afforded military detainees.

The precise operations that the directive authorizes are unclear, and what the military has done to follow through on the order is uncertain. The document, a copy of which was viewed by The New York Times, provides few details about continuing missions or intelligence-gathering operations.

Several government officials who described the impetus for the order would speak only on condition of anonymity because the document is classified. Spokesmen for the White House and the Pentagon declined to comment for this article. The Times, responding to concerns about troop safety raised by an official at United States Central Command, the military headquarters run by General Petraeus, withheld some details about how troops could be deployed in certain countries.

The seven-page directive appears to authorize specific operations in Iran, most likely to gather intelligence about the country’s nuclear program or identify dissident groups that might be useful for a future military offensive. The Obama administration insists that for the moment, it is committed to penalizing Iran for its nuclear activities only with diplomatic and economic sanctions. Nevertheless, the Pentagon has to draw up detailed war plans to be prepared in advance, in the event that President Obama ever authorizes a strike.

“The Defense Department can’t be caught flat-footed,” said one Pentagon official with knowledge of General Petraeus’s order.

The directive, the Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Force Execute Order, signed Sept. 30, may also have helped lay a foundation for the surge of American military activity in Yemen that began three months later.

Special Operations troops began working with Yemen’s military to try to dismantle Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, an affiliate of Osama bin Laden’s terror network based in Yemen. The Pentagon has also carried out missile strikes from Navy ships into suspected militant hideouts and plans to spend more than $155 million equipping Yemeni troops with armored vehicles, helicopters and small arms.

Officials said that many top commanders, General Petraeus among them, have advocated an expansive interpretation of the military’s role around the world, arguing that troops need to operate beyond Iraq and Afghanistan to better fight militant groups.

The order, which an official said was drafted in close coordination with Adm. Eric T. Olson, the officer in charge of the United States Special Operations Command, calls for clandestine activities that “cannot or will not be accomplished” by conventional military operations or “interagency activities,” a reference to American spy agencies.

While the C.I.A. and the Pentagon have often been at odds over expansion of clandestine military activity, most recently over intelligence gathering by Pentagon contractors in Pakistan and Afghanistan, there does not appear to have been a significant dispute over the September order.

A spokesman for the C.I.A. declined to confirm the existence of General Petraeus’s order, but said that the spy agency and the Pentagon had a “close relationship” and generally coordinate operations in the field.

“There’s more than enough work to go around,” said the spokesman, Paul Gimigliano. “The real key is coordination. That typically works well, and if problems arise, they get settled.”

During the Bush administration, Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld endorsed clandestine military operations, arguing that Special Operations troops could be as effective as traditional spies, if not more so.

Unlike covert actions undertaken by the C.I.A., such clandestine activity does not require the president’s approval or regular reports to Congress, although Pentagon officials have said that any significant ventures are cleared through the National Security Council. Special Operations troops have already been sent into a number of countries to carry out reconnaissance missions, including operations to gather intelligence about airstrips and bridges.

Some of Mr. Rumsfeld’s initiatives were controversial, and met with resistance by some at the State Department and C.I.A. who saw the troops as a backdoor attempt by the Pentagon to assert influence outside of war zones. In 2004, one of the first groups sent overseas was pulled out of Paraguay after killing a pistol-waving robber who had attacked them as they stepped out of a taxi.

A Pentagon order that year gave the military authority for offensive strikes in more than a dozen countries, and Special Operations troops carried them out in Syria, Pakistan and Somalia.

In contrast, General Petraeus’s September order is focused on intelligence gathering — by American troops, foreign businesspeople, academics or others — to identify militants and provide “persistent situational awareness,” while forging ties to local indigenous groups.

Thom Shanker and Eric Schmitt contributed reporting