U.S. Empire Still Incoherent After All These Years

Without solid economic, political and ideological bases, the U.S. lacks the legitimacy and authority it needs to operate beyond its borders, argues Nicolas J.S. Davies in this essay.

I recently reread Michael Mann’s book, Incoherent Empire, which he wrote in 2003, soon after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Mann is a sociology professor at UCLA and the author of a four-volume series called The Sources of Social Power, in which he explained the major developments of world history as the interplay between four types of power: military, economic, political, and ideological.

In Incoherent Empire, Mann used the same framework to examine what he called the U.S.’s “new imperialism” after the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. He predicted that, “The American Empire will turn out to be a military giant; a back-seat economic driver; a political schizophrenic; and an ideological phantom.”

What struck me most forcefully as I reread Incoherent Empire was that absolutely nothing has changed in the “incoherence” of U.S. imperialism. If I picked up the book for the first time today and didn’t know it was written 15 years ago, I could read nearly all of it as a perceptive critique of American imperialism exactly as it exists today.

In the intervening 15 years, U.S. policy failures have resulted in ever-spreading violence and chaos that affect hundreds of millions of people in at least a dozen countries. The U.S. has utterly failed to bring any of its neo-imperial wars to a stable or peaceful end. And yet the U.S. imperial project sails on, seemingly blind to its consistently catastrophic results.

Instead, U.S. civilian and military leaders shamelessly blame their victims for the violence and chaos they have unleashed on them, and endlessly repackage the same old war propaganda to justify record military budgets and threaten new wars.

But they never hold themselves or each other accountable for their catastrophic failures or the carnage and human misery they inflict. So they have made no genuine effort to remedy any of the systemic problems, weaknesses and contradictions of U.S. imperialism that Michael Mann identified in 2003 or that other critical analysts like Noam Chomsky, Gabriel Kolko, William Blum and Richard Barnet have described for decades.

Let’s examine each of Mann’s four images of the foundations of the U.S.’s Incoherent Empire, and see how they relate to the continuing crisis of U.S. imperialism that he presciently foretold:

Military Giant

As Mann noted in 2003, imperial armed forces have to do four things: defend their own territory; strike offensively; conquer territories and people; then pacify and rule them.

Today’s U.S. military dwarfs any other country’s military forces. It has unprecedented firepower, which it can use from unprecedented distances to kill more people and wreak more destruction than any previous war machine in history, while minimizing U.S. casualties and thus the domestic political blowback for its violence.

But that’s where its power ends. When it comes to actually conquering and pacifying a foreign country, America’s technological way of war is worse than useless. The very power of U.S. weapons, the “Robocop” appearance of American troops, their lack of language skills and their isolation from other cultures make U.S. forces a grave danger to the populations they are charged with controlling and pacifying, never a force for law and order, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan or North Korea.

John Pace, who headed the UN Assistance Mission to Iraq during the U.S. occupation compared U.S. efforts to pacify the country to “trying to swat a fly with a bomb.”

Burhan Fasa’a, an Iraqi reporter for Lebanon’s LBC TV network, survived the second U.S. assault on Fallujah in November 2004. He spent nine days in a house with a population that grew to 26 people as neighboring homes were damaged or destroyed and more and more people sought shelter with Fasa’a and his hosts.

Finally a squad of U.S. Marines burst in, yelling orders in English that most of the residents didn’t understand and shooting them if they didn’t respond.

“Americans did not have interpreters with them, “ Fasa’a explained, “so they entered houses and killed people because they didn’t speak English… Soldiers thought the people were rejecting their orders, so they shot them. But the people just couldn’t understand them.”

This is one personal account of one episode in a pattern of atrocities that grinds on, day in day out, in country after country, as it has done for the last 16 years. To the extent that the Western media cover these atrocities at all, the mainstream narrative is that they are a combination of unfortunate but isolated incidents and the “normal” horrors of war.

But that is not true. They are the direct result of the American way of war, which prioritizes “force protection” over the lives of human beings in other countries to minimize U.S. casualties and thus domestic political opposition to war. In practice, this means using overwhelming and indiscriminate firepower in ways that make it impossible to distinguish combatants from non-combatants or protect civilians from the horrors of war as the Geneva Conventions require.

U.S. rules of engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan have included: systematic, theater-wide use of torture; orders to “dead-check” or kill wounded enemy combatants; orders to “kill all military-age males” during certain operations; and “weapons-free” zones that mirror Vietnam-era “free-fire” zones.

When lower ranks have been prosecuted for war crimes against civilians, they have been acquitted or given light sentences because they were acting on orders from senior officers. But courts martial have allowed the senior officers implicated in these cases to testify in secret or have not called them to testify at all, and none have been prosecuted.

After nearly a hundred deaths in U.S. custody in Iraq and Afghanistan, including torture deaths that are capital crimes under U.S. federal law, the harshest sentence handed down was a 5 month prison sentence, and the most senior officer prosecuted was a major, although the orders to torture prisoners came from the very top of the chain of command. As Rear Admiral John Hutson, the retired Judge Advocate General of the U.S. Navy, wrote in Human Rights First’s Command’s Responsibility report after investigating just 12 of these deaths,

“One such incident would be an isolated transgression; two would be a serious problem; a dozen of them is policy.”

So the Military Giant is not just a war machine. It is also a war crimes machine.

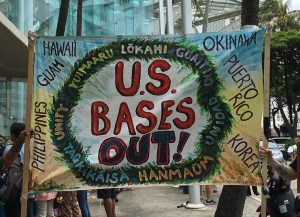

The logic of force protection and technological warfare also means that the roughly 800 U.S. military bases in other countries are surrounded by barbed wire and concrete blast-walls and staffed mainly by Americans, so that the 290,000 U.S. troops occupying 183 foreign countries have little contact with the local people their empire aspires to rule.

Donald Rumsfeld described this empire of self-contained bases as “lily pads,” from which his forces could hop like frogs from one base to another by plane, helicopter or armored vehicle, or launch strikes on the surrounding territory, without exposing themselves to the dangers of meeting the locals.

Robert Fisk, the veteran Middle East reporter for the U.K.’s Independent newspaper, had another name for these bases: “crusader castles”– after the medieval fortresses built by equally isolated foreign invaders a thousand years ago that still dot the landscape of the Middle East.

Michael Mann contrasted the isolation of U.S. troops in their empire of bases to the lives of British officers in India, “where officers’ clubs were typically on the edge of the encampment, commanding the nicest location and view. The officers were relaxed about their personal safety, sipping their whisky and soda and gin and tonic in full view of the natives, (who) comprised most of the inhabitants – NCOs and soldiers, servants, stable-hands, drivers and sometimes their families.”

In 1945, a wiser generation of American leaders brought to their senses by the mass destruction of two world wars realized the imperial game was up. They worked hard to frame their new-found power and economic dominance within an international system that the rest of the world would accept as legitimate, with a central role for President Roosevelt’s vision of the United Nations.

Roosevelt promised that his “permanent structure of peace,” would, “spell the end of the system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the expedients that have been tried for centuries – and have always failed,” and that “the forces of aggression (would be) permanently outlawed.”

America’s World War II leaders were wisely on guard against the kind of militarism they had confronted and defeated in Germany and Japan. When an ugly militarism reared its head in the U.S. in the late 1940s, threatening a “preemptive” nuclear war to destroy the USSR before it could develop its own nuclear deterrent, General Eisenhower responded forcefully in a speech to the U.S. Conference of Mayors in St. Louis,

“I decry loose and sometimes gloating talk about the high degree of security implicit in a weapon that might destroy millions overnight,” Eisenhower declared. “Those who measure security solely in terms of offensive capacity distort its meaning and mislead those who pay them heed. No modern nation has ever equaled the crushing offensive power attained by the German war machine in 1939. No modern country was broken and smashed as was Germany six years later.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, the chief US representative at the London Conference that drew up the Nuremberg Principles in 1945, stated as the official U.S. position,

“If certain acts in violation of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United States does them or whether Germany does them, and we are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.”

That was the U.S. government of 1945 explicitly agreeing to the prosecution of Americans who commit aggression, which Jackson and the judges at Nuremberg defined as “the supreme international crime.” That would now include the last six U.S. presidents: Reagan (Grenada and Nicaragua), Bush I (Panama), Clinton (Yugoslavia), Bush II (Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and Somalia), Obama (Pakistan, Libya, Syria and Yemen) and Trump (Syria and Yemen).

Since Mann wrote Incoherent Empire in 2003, the Military Giant has rampaged around the world waging wars that have killed millions of people and wrecked country after country. But its unaccountable campaign of serial aggression has failed to bring peace or security to any of the countries it has attacked or invaded. As even some members of the U.S. military now recognize, the mindless violence of the Military Giant serves no rational or constructive purpose, imperialist or otherwise.

Economic Back Seat Driver

In 2003, Michael Mann wrote that,

“The U.S. productive engine remains formidable, the global financial system providing its fuel. But the U.S. is only a back-seat driver since it cannot directly control either foreign investors or foreign economies.”

Since 2003, the U.S. role in the global economy has declined further, now comprising only 22% of global economic activity, compared with 40% at the height of its economic dominance in the 1950s and 60s. China is displacing the U.S. as the largest trading partner of countries around the world, and its “new silk road” initiatives are building the infrastructure to cement and further expand its role as the global hub of manufacturing and commerce.

The U.S. can still wield its financial clout as an arsenal of carrots and sticks to pressure poorer, weaker countries do what it wants. But this is a far cry from the actions of an imperial power that actually rules far-flung territories and subjects on other continents. As Mann put it, “Even if they are in debt, the U.S. cannot force reform on them. In the global economy, it is only a back-seat driver, nagging the real driver, the sovereign state, sometimes administering sharp blows to his head.”

At the extreme, the U.S. uses economic sanctions as a brutal form of economic warfare that hurts and kills ordinary people, while generally inflicting less pain on the leaders who are their nominal target. U.S. leaders claim that the pain of economic sanctions is intended to force people to abandon and overthrow their leaders, a way to achieve regime change without the violence and horror of war. But Robert Pape of the University of Chicago conducted an extensive study of the effects of sanctions and concluded that only 5 out of 115 sanctions regimes have ever achieved that goal.

When sanctions inevitably fail, they can still be useful to U.S. officials as part of a political narrative to blame the victims and frame war as a last resort. But this is only a political ploy, not a legal pretext for war.

A secondary goal of all such imperial bullying is to make an example of the victims to put other weak countries on notice that resisting imperial demands can be dangerous. The obvious counter to such strategies is for poorer, weaker countries to band together to resist imperial bullying, as in collective groupings like CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), and also in the UN General Assembly, where the U.S. often finds itself outvoted.

The dominant position of the U.S. and the dollar in the international financial system have given the U.S. a unique ability to finance its imperial wars and global military expansion without bankrupting itself in the process. As Mann described in Incoherent Empire,

“In principle, the world is free to withdraw its subsidies to the U.S., but unless the U.S. really alienates the world and over-stretches its economy, this is unlikely. For the moment, the U.S. can finance substantial imperial activity. It does so carefully, spending billions on its strategic allies, however unworthy and oppressive they may be.”

The economic clout of the U.S. back-seat driver was tested in 2003 when it deployed maximum pressure on other countries to support its invasion of Iraq. Chile, Mexico, Pakistan, Guinea, Angola and Cameroon were on the Security Council at the time but were all ready to vote against the use of force. It didn’t help the U.S. case that it had failed to deliver the “carrots” it promised to the countries who voted for war on Iraq in 1991, nor that the money it promised Pakistan for supporting its invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was not paid until the U.S. wanted its support again in 2003 over Iraq.

Mann concluded,

“An administration which is trying to cut taxes while waging war will not be able to hand out much cash around the world. This back-seat driver will not pay for the gas. It is difficult to build an Empire without spending money.”

Fifteen years later, remarkably, the wealthy investors of the world have continued to subsidize U.S. war-making by investing in record U.S. debt, and a deceptive global charm offensive by President Obama partially rebuilt U.S. alliances. But the U.S. failure to abandon its illegal policies of aggression and war crimes have only increased its isolation since 2003, especially from countries in the Global South. People all over the world now tell pollsters they view the U.S. as the greatest threat to peace in the world.

It is also possible that their U.S. debt holdings give China and other creditors (Germany?) some leverage by which they can ultimately discipline U.S. imperialism. In 1956, President Eisenhower reportedly threatened to call in the U.K.’s debts if it did not withdraw its forces from Egypt during the Suez crisis, and there has long been speculation that China could exercise similar economic leverage to stop U.S. aggression at some strategic moment.

It seems more likely that boom and bust financial bubbles, shifts in global trade and investment and international opposition to U.S. wars will more gradually erode U.S. financial hegemony along with other forms of power.

Michael Mann wrote in 2003 that the world was unlikely to “withdraw its subsidies” for U.S. imperialism “unless the U.S. really alienates the world and over-stretches its economy.” But that prospect seems more likely than ever in 2018 as President Trump seems doggedly determined to do both.

Political Schizophrenic

In its isolated fantasy world, the Political Schizophrenic is the greatest country in the world, the “shining city on a hill,” the land of opportunity where anyone can find their American dream. The rest of the world so desperately wants what we have that we have to build a wall to keep them out. Our armed forces are the greatest force for good that the world has ever known, valiantly fighting to give other people the chance to experience the democracy and freedom that we enjoy.

But if we seriously compare the U.S. to other wealthy countries, we find a completely different picture. The United States has the most extreme inequality, the most widespread poverty, the least social and economic mobility and the least effective social safety net of any technologically advanced country.

America is exceptional, not in the imaginary blessings our Political Schizophrenic politicians take credit for, but in its unique failure to provide healthcare, education and other necessities of life to large parts of its population, and in its systematic violations of the UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions and other binding international treaties.

If the U.S. was really the democracy it claims to be, the American public could elect leaders who would fix all these problems. But the U.S. political system is so endemically corrupt that only a Political Schizophrenic could call it a democracy. Former President Jimmy Carter believes that the U.S. is now ”just an oligarchy, with unlimited political bribery.” U.S. voter turnout is understandably among the lowest in the developed world.

Sheldon Wolin, who taught political science at Berkeley and Princeton for 40 years, described the actually existing U.S. political system as “inverted totalitarianism.” Instead of abolishing democratic institutions on the “classical totalitarian” model, the U.S.’s inverted totalitarian system preserves the hollowed-out trappings of democracy to falsely legitimize the oligarchy and political bribery described by President Carter.

As Wolin explained, this has been more palatable and sustainable, and therefore more effective, than the classical form of totalitarianism as a means of concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a corrupt ruling class.

The corruption of the U.S. political system is increasingly obvious to Americans, but also to people in other countries. Billion-dollar U.S.-style “elections” would be illegal in most developed countries, because they inevitably throw up corrupt leaders who offer the public no more than empty slogans and vague promises to disguise their plutocratic loyalties.

In 2018, U.S. party bosses are still determined to divide us along the artificial fault-lines of the 2016 election between two of the most unpopular candidates in history, as if their vacuous slogans, mutual accusations and plutocratic policies define the fixed poles of American politics and our country’s future.

The Political Schizophrenic’s noise machine is working overtime to stuff the alternate visions of Bernie Sanders, Jill Stein and other candidates who challenge the corrupt status quo down the “memory hole,” by closing ranks, purging progressives from DNC committees and swamping the airwaves with Trump tweets and Russiagate updates.

Ordinary Americans who try to engage with or confront members of the corrupt political, business and media class find it almost impossible. The Political Schizophrenic moves in a closed and isolated social circle, where the delusions of his fantasy world or “political reality” are accepted as incontrovertible truths. When real people talk about real problems and suggest real solutions to them, he dismisses us as naive idealists. When we question the dogma of his fantasy world, he thinks we are the ones who are out of touch with reality. We cannot communicate with him, because he lives in a different world and speaks a different language.

It is difficult for the winners in any society to recognize that their privileges are the product of a corrupt and unfair system, not of their own superior worth or ability. But the inherent weakness of “inverted totalitarianism” is that the institutions of American politics still exist and can still be made to serve democracy, if and when enough Americans wake up from this Political Schizophrenia, organize around real solutions to real problems, and elect people who are genuinely committed to turning those solutions into public policy.

As I was taught when I worked with schizophrenics as a social worker, they tend to become agitated and angry if you question the reality of their fantasy world. If the patient in question is also armed to the teeth, it is a matter of life and death to handle them with kid gloves.

The danger of a Political Schizophrenic armed with a trillion dollar a year war machine and nuclear weapons is becoming more obvious to more of our neighbors around the world as each year goes by. In 2017, 122 of them voted to approve the new UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

U.S. allies have pursued an opportunistic policy of appeasement, as many of the same countries did with Germany in the 1930s. But Russia, China and countries in the Global South have gradually begun to take a firmer line, to try to respond to U.S. aggression and to shepherd the world through this incredibly dangerous transitional period to a multipolar, peaceful and sustainable world. The Political Schizophrenic has, predictably, responded with propaganda, demonization, threats and sanctions, now amounting to a Second Cold War.

Ideological Phantom

During the First Cold War, each side presented its own society in an idealized way, but was more honest about the flaws and problems of its opposite number. As a former East German now living in the U.S. explained to me,

“When our government and state media told us our society was perfect and wonderful, we knew they were lying to us. So when they told us about all the social problems in America, we assumed they were lying about them too.”

Now living in the U.S., he realized that the picture of life in the U.S. painted by the East German media was quite accurate, and that there really are people sleeping in the street, people with no access to healthcare and widespread poverty.

My East German acquaintance came to regret that Eastern Europe had traded the ills of the Soviet Empire for the ills of the U.S. Empire. Nobody ever explained to him and his friends why this had to be a “take it or leave it” neoliberal package deal, with “shock therapy” and large declines in living standards for most Eastern Europeans. Why could they not have Western-style political freedom without giving up the social protections and standard of living they enjoyed before?

American leaders at the end of the Cold War lacked the wisdom and caution of their predecessors in 1945, and quickly succumbed to what Mikhail Gorbachev now calls “triumphalism.” The version of capitalism and “managed democracy” they expanded into Eastern Europe was the radical neoliberal ideology introduced by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and consolidated by Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. The people of Eastern Europe were no more or less vulnerable to neoliberalism’s siren song than Americans and Western Europeans.

The unconstrained freedom of ruling classes to exploit working people that is the foundation of neoliberalism has always been an Ideological Phantom, as Michael Mann called it, with a hard core of greed and militarism and an outer wrapping of deceptive propaganda.

So the “peace dividend” most people longed for at the end of the Cold War was quickly trumped by the “power dividend.” Now that the U.S. was no longer constrained by the fear of war with the U.S.S.R., it was free to expand its own global military presence and use military force more aggressively. As Michael Mandelbaum of the Council on Foreign Relations crowed to the New York Times as the U.S. prepared to attack Iraq in 1990,

“For the first time in 40 years we can conduct military operations in the Middle East without worrying about triggering World War III.”

Without the Cold War to justify U.S. militarism, the prohibition against the threat or use of military force in the UN Charter took on new meaning, and the Ideological Phantom embarked on an urgent quest for political rationales and propaganda narratives to justify what international law clearly defines as the crime of aggression.

Madeleine Albright and Colin Powell

During the transition to the incoming Clinton administration after the 1992 election, Madeleine Albright confronted General Colin Powell at a meeting and asked him,

“What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?”

The correct answer would have been that, after the end of the Cold War, the legitimate defense needs of the U.S. required much smaller, strictly defensive military forces and a greatly reduced military presence around the world. Former Cold Warriors, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and Assistant Secretary Lawrence Korb, told the Senate Budget Committee in 1989 that the U.S. military budget could safely be cut in half over 10 years. Instead, it is now even higher than when they said that (after adjusting for inflation).

The U.S.’s Cold War Military Industrial Complex was still dominant in Washington. All it lacked was a new ideology to justify its existence. But that was just an interesting intellectual challenge, almost a game, for the Ideological Phantom.

The ideology that emerged to justify the U.S.’s new imperialism is a narrative of a world threatened by “dictators” and “terrorists,” with only the power of the U.S. military standing between the “free” people of the American Empire and the loss of all we hold dear. Like the fantasy world of the Political Schizophrenic, this is a counter-factual picture of the world that only becomes more ludicrous with each year that passes and each new phase of the ever-expanding humanitarian and military catastrophe it has unleashed.

The Ideological Phantom defends the world against terrorists on a consistently selective and self-serving basis. It is always ready to recruit, arm and support terrorists to fight its enemies, as in Afghanistan and Central America in the 1980s or more recently in Libya and Syria. U.S. support for jihadis in Afghanistan led to the worst act of terrorism on U.S. soil on September 11th 2001.

But that didn’t prevent the U.S. and its allies from supporting the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and other jihadis in Libya less than ten years later, leading to the Manchester Arena bombing by the son of an LIFG member in 2017. And it hasn’t prevented the CIA from pouring thousands of tons of weapons into Syria, from sniper rifles to howitzers, to arm Al Qaeda-led fighters from 2011 to the present.

When it comes to opposing dictators, the Ideological Phantom’s closest allies always include the most oppressive dictators in the world, from Pinochet, Somoza, Suharto, Mbuto and the Shah of Iran to its newest super-client, Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman of Saudi Arabia. In the name of freedom and democracy, the U.S. keeps overthrowing democratically elected leaders and replacing them with coup-leaders and dictators, from Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954 to Haiti in 2004, Honduras in 2009 and Ukraine in 2014.

Nowhere is the Ideological Phantom more ideologically bankrupt than in the countries the U.S. has dispatched its armed forces and foreign proxy forces to “liberate” since 2001: Afghanistan; Iraq; Libya; Syria; Somalia and Yemen. In every case, ordinary people have been slaughtered, devastated and utterly disillusioned by the ugly reality behind the Phantom’s mask.

In Afghanistan, after 16 years of U.S. occupation, a recent BBC survey found that people feel safer in areas governed by the Taliban. In Iraq, people say their lives were better under Saddam Hussein. Libya has been reduced from one of the most stable and prosperous countries in Africa to a failed state ruled by competing militias, while Somalia, Syria and Yemen have met similar fates.

Incredibly, American ideologists in the 1990s saw the Ideological Phantom’s ability to project counter-factual, glamorized images of itself as a source of irresistible ideological power. In 1997, Major Ralph Peters, who is better known as a best-selling novelist, turned his vivid imagination and skills as a fiction writer to the bright future of the Ideological Phantom in a military journal article titled “Constant Conflict.”

Peters imagined an endless campaign of “information warfare” in which U.S. propagandists, aided by Hollywood and Silicon Valley, would overwhelm other cultures with powerful images of American greatness that their own cultures could not resist.

“One of the defining bifurcations of the future will be the conflict between information masters and information victims,” Peters wrote. “We are already masters of information warfare… (we) will be writing the scripts, producing (the videos) and collecting the royalties.”

But while Peters’ view of U.S. imperialism was based on media, technology and cultural chauvinism, he was not suggesting that the Ideological Phantom would conquer the world without a fight – quite the opposite. Peters’ vision was a war plan, not a futuristic fantasy.

“There will be no peace,” he wrote. “At any given moment for the rest of our lives, there will be multiple conflicts in mutating forms around the globe. Violent conflict will dominate the headlines, but cultural and economic struggles will be steadier and ultimately more decisive. The de facto role of the U.S. armed forces will be to keep the world safe for our economy and open to our cultural assault.”

“To those ends,” he added, “We will do a fair amount of killing.”

Conclusion

After reviewing the early results of the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2003, Michael Mann concluded,

“We saw in action that the new imperialism turned into simple militarism.”

Without solid economic, political and ideological bases, the Military Giant lacks the economic, political and ideological power and authority required to govern the world beyond its shores. The Military Giant can only destroy and bring chaos, never rebuild or bring order.

The sooner the people of the U.S. and the world wake up to this dangerous and destructive reality, the sooner we can begin to lay the new economic, political and ideological foundations of a peaceful, just and sustainable world.

Like past aggressors, the Military Giant is sowing the seeds of his own destruction. But there is only one group of people in the world who can peacefully tame him and cut him down to size. That is us, the 323 million people who call ourselves Americans.

We have waited far too long to claim the peace dividend that our warmongering leaders stole from us after the end of the First Cold War. Millions of our fellow human beings have paid the ultimate price for our confusion, weakness and passivity.

Now we must be united, clear and strong as we begin the essential work of transforming our country from an Incoherent Empire into an Economic High-Speed Train to a Sustainable Future; a Real Political Democracy; an Ideological Humanitarian – and a Military Law-Abiding Citizen.

*

Nicolas J.S. Davies is the author of Blood On Our Hands: the American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq. He also wrote the chapters on “Obama at War” in Grading the 44th President: a Report Card on Barack Obama’s First Term as a Progressive Leader.