U.S., Canada Side with Fanatical Coup Regime in Bolivia

Racist interim government vows "God has returned to the palace"

On November 10, 2019, a U.S.-backed group of neofascists in Bolivia deposed the government of Evo Morales on spurious accusations of electoral fraud. The coup government’s first act was to unleash the army and police on mainly Indigenous protestors in the capital of La Paz, killing at least 10 people. Further massacres pushed the coup’s death toll above 30, with hundreds more wounded in clashes between supporters of Morales’s Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party and state police.

The coup regime is now led by Jeanine Áñez, a Christian-fundamentalist senator and opponent of Morales, who in 2013 tweeted (translation):

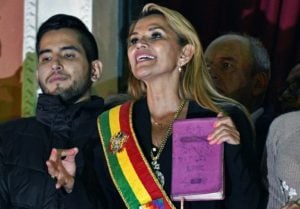

Image on the right: Deputy Senate speaker Jeanine Anez speaks from the balcony of the government Quemado Palace in La Paz after proclaiming herself the country’s interim president (AFP / Aizar RALDES)

“I dream of a Bolivia free of indigenous satanic rites, the city is not for ‘Indians,’ they better go to the highlands or El Chaco.”

On claiming the presidency after the army “asked” Morales to step down (he fled to Mexico following threats to his life and has since moved to Argentina), Áñez declared,

“Thank God the Bible has returned to the Bolivian government.”

About two-thirds of Bolivia’s population is Indigenous, forming a major part of Morales’s support base. Before the coup, MAS held majorities in both the Bolivian chamber of deputies and the senate.

Entering the presidential palace on November 10, also with a bible in his hand, was Luis Camacho (image below), a millionaire neofascist and prominent member of both the U.S.-supported right-wing separatist group Santa Cruz Civic Committee (of Santa Cruz province) and its paramilitary Youth Union (also U.S.-funded), which attacks Indigenous people. Both groups were involved in an attempt on Morales’s life in 2009.

“God has returned to the palace,” Camacho posted to Facebook on November 10. “To those who did not believe in this struggle I say God exists and is now going to govern Bolivia for all Bolivians!”

The coup regime has scheduled new elections for May 3, 2020, but these are unlikely to be free and fair. As Alexander Main, director of international policy for the U.S.-based Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), tells me, many MAS leaders have been targeted with dubious charges.

“Morales himself is unlikely to return to Bolivia to help support the MAS campaign, as he has been accused of terrorism and sedition by top de facto officials,” says Main. “It appears likely that the de facto authorities will do all they can to prevent MAS leaders from running and they may also create an environment of fear and intimidation for MAS supporters that want to be involved in the electoral campaign.”

Angus McNelly, lecturer in Latin American politics at Queen Mary University of London (U.K.), agrees with Main, pointing out that 100 MAS politicians have been arrested or were forced to flee from the law. Former government minister Carlos Romero was blockaded in his house by a civilian vigil after his address was leaked and had to seek medical care for lack of food and water.

“Romero was arrested while he was at hospital receiving medical care,” McNelly notes. “This attack on the MAS might mean that it cannot field its strongest candidates, and that some sections [of the populace] are afraid to vote for the MAS.”

*

Morales was accused by the opposition of winning the October 20, 2019 election through fraud. The U.S.-dominated Organization of American States (OAS), which sent an electoral observation mission to Bolivia, announced the day after the vote—but before all the votes were counted—its “deep concern and surprise at the drastic and hard-to-explain change in the trend of the preliminary results.”

However, a CEPR analysis of the election returns showed “no evidence that irregularities or fraud affected the official result that gave Morales a first-round victory.” In fact, the centre declared on November 8, “statistical analysis shows that it was predictable that Morales would obtain a first-round win, based on the results of the first 83.85 per cent of votes in a rapid count that showed Morales leading runner-up Carlos Mesa by less than 10 points.”

Mark Weisbrot, co-director of CEPR, accused the OAS of lying to the public about the election results, pointing out it was “highly questionable” for the organization to issue a press statement doubting the election results “without providing any evidence for doing so.” He added that the OAS “isn’t all that independent at the moment,” considering the Trump administration was “actively promoting this military coup” alongside its right-wing allies in the region. These allies include the former Argentine government of Mauricio Macri and the Bolsonaro presidency in Brazil. Immediately following the coup, Chrystia Freeland, then Canadian foreign minister, declared her government’s support for new elections, claiming, “It is clear that the will of the Bolivian people and the democratic process were not respected.”

The OAS statement on election results put the coup machinery in motion. Camacho’s paramilitary gangs served as shock troops, kidnapping and torturing elected officials, burning public buildings, ransacking Morales’s home, attacking his ministers and holding their families hostage to compel their resignations. Bolivian general Williams Kaliman Romero, who trained at the U.S.-run School of the Americas, then “suggested” to Morales on November 10 that he should resign.

According to Sacha Llorenti, Bolivian ambassador to the United Nations, “Loyal members of Morales’s security team showed him messages in which people were offering them $50,000 if they would hand him over.” Some reports out of Brazil and Argentina have claimed Kaliman was paid US$1 million by the U.S. for his role in the coup and that he has since fled to the United States, along with other Bolivian police chiefs who were paid to look the other way on the day of the coup. As Marjorie Cohn, professor emerita at Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego, puts it, “The United States’ fingerprints are all over the coup.”

Morales claimed in an interview with Agence France Press that the U.S. overthrew him to gain control of Bolivia’s vast lithium reserves. Lithium is used to make batteries for electric cars and Bolivia has the largest deposits of the mineral in the world. Demand for lithium is expected to soar as the manufacture of electric cars expands. According to Morales, Washington has not “forgiven” him for pursuing lithium extraction projects with China and Russia rather than the U.S. “Industrialized countries don’t want competition,” he said, “that’s why I am absolutely convinced, it’s a coup against lithium. We were going to set the price of lithium.”

*

Washington has also been opposed to Morales’s remarkable achievements in the areas of poverty reduction, wealth generation and redistribution, the nationalization of mineral wealth and the enshrinement of Indigenous rights. All of these dramatically signified reduced U.S. control over Bolivia highlighted by the expulsion of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in 2013 and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 2008, partly for “political interference.”

“Bolivia made enormous social and economic progress during the Morales presidency,” Main tells me. “Thanks to the Morales government’s heterodox, state-led economic policies—which promoted strong growth and better redistribution of the country’s wealth—poverty was reduced by 46% and extreme poverty by 60%. Unemployment declined by 50%. An important factor behind these remarkable advances that should be noted by other governments in the region was the fact that public investment under Morales reached the highest levels of the region.”

Morales also almost tripled Bolivia’s per capita GDP and instituted three cash transfer programs for mothers, children and pensioners. Of course, all of Morales’s policies have not been beyond objection. There has been a contradiction between MAS’s support for Indigenous rights and the rights of nature (both embedded in the Bolivian constitution) and his continued promotion of and dependence on mineral extraction for the generation of revenue.

“Countries with left- and right-wing governments across the region have all pursued an extractive agenda in the region in large part due to the way Latin America has been inserted into the world market,” says McNelly. “The difference between Morales and his predecessors is that his government was able to capture more of the surplus and redirect it toward the Bolivian population. The problem for Morales is that the MAS was supposedly pursuing an alternative form of development through the notion of vivir bien (living well).”

The social base of the MAS is largely rural and drawn from the Indigenous peasantry in the Andean highlands and the valleys of Cochabamba, McNelly explains. But these groups have very different conceptions of nature and how to manage resources.

“What essentially happened was that arguments for exploiting Bolivia’s extensive natural wealth for the good of all Bolivians—particularly those who were the social base of the MAS who saw the greatest material improvement—won over arguments for protecting Mother Earth.”

McNelly adds that this brought Indigenous communities benefiting from extractivism into conflict with other Indigenous nations that were “displaced and dispossessed” by such activities. Prominent examples are the conflict over the construction of the highway through the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), the El Bala and Chepete hydroelectric dams and the Mallku Khota mine.

Domestic decisions about the structuring of the economy will always be limited by the ways a country has been inserted in the global economy, says McNelly. “The question is whether Bolivia has the option to follow an alternative pathway [as] a small, poor country with little to no room to manoeuver in negotiations with superpowers such as China or the United States. The whole region is inserted as a source of primary resources and changing a country’s position in the global economy is very difficult.”

The coup regime, which represents Bolivia’s white-dominated ruling class and is allied to western multinational corporations, will almost certainly reverse Morales’s resource nationalizations and wealth redistribution and poverty reduction programs if they are elected to government in May. In a January 3 Unitel (local Bolivian media) election poll, 20.7% of Bolivians said they would vote for MAS, followed by 15.7% for Áñez.

On January 19, Morales announced in Argentina that the MAS candidates for president and vice-president would be Luis Arce (former economy minister) and David Choquehuanca (former foreign minister) respectively. Jorge Derpic, assistant professor in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the University of Georgia (U.S.), told Al Jazeera these choices were aimed at getting middle class votes and Indigenous votes. “MAS may be able to win the election with these two candidates,” Derpic predicted.

McNelly is more skeptical, pointing again to the massive attacks on MAS politicians by the right. “Although it is ahead in the polls, the MAS is unlikely to win in the May elections,” he tells me.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Monitor (CCPA Monitor).

Asad Ismi covers international affairs for the Monitor.