Two Days Before 9/11: The Assassination of the Leader of Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance Ahmad Shah Massoud

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

This article was originally published on Global Research in September 2003.

It happened two days before September 11, 2001, media reports presented these two events: 9/11 and 9/11 as totally unrelated.

***

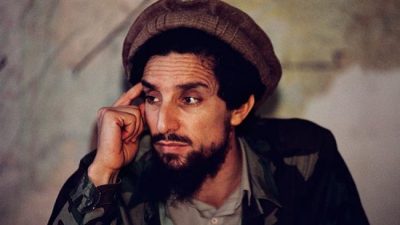

On September 9, 2001, two days before the cataclysmic attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, Ahmad Shah Massoud, commander of the United Front guerrilla opposition to Afghanistan’s Taliban regime, was assassinated in the Afghan town of Khvajeh Baha od Din by two Arab men posing as journalists. Both of the assassins died — one in the attack itself, blown up with his own bomb along with Massoud, and the other, it seems, was shot while trying to escape shortly afterwards.(1)

Journalists commonly attribute the murder either to al Qaeda or to the Taliban. (2) That seems logical enough. Massoud’s United Front was fighting a war against the Taliban at the time. The Taliban were in turn protecting al Qaeda, an organization blamed for a number of sophisticated terrorist attacks, including those on 9/11. Simple as these explanations may be, Massoud’s murder has never been solved. The details of the assassination, which included an explosive charge disguised as a battery pack for a video camera, the acquisition of stolen passports, and the death of both assassins, at different times and by different means — suggest a sophisticated conspiracy. Dead men tell no tales, and in this case, neither have the living. The Taliban, for their part, have denied any involvement in Massoud’s death.

Last March [2003], a Belgian court indicted thirteen suspects on charges related to the murder, including the theft and sale of fraudulent passports found on the bodies of the assassins, allegedly linking them, and the assassination generally, to al Qaeda. (3) Yet nothing further has been reported since March, and the news media of the world seem to have forgotten about it.

Poster of Massoud in Kabul, 2013 (Source: CC BY 2.0)

But Massoud’s assassination is important for several reasons. First of all, Ahmad Shah Massoud has [2003] become the national hero of Afghanistan. There are pictures of him everywhere in Kabul and Herat where I visited, at least — on streetcorners, government buildings, and the dashboards of cars. The second anniversary of Massoud’s death was celebrated last week in the national stadium, in a ceremony attended by practically every senior member of the government. (4) Massoud has become an abstract symbol of the defeat of the Taliban, the defeat of the Soviet Union, and of the Afghan “resistance” generally. The French have even commissioned a series of Ahmad Shah Massoud postage stamps. Just before his death, Massoud had made a whirlwind tour of Europe, including Paris, to drum up support for his anti-Taliban campaign.

Image on the right: Ahmad Shah Massoud (right) with Pashtun anti-Taliban leader Abdul Qadir (Afghan leader) (brother of Abdul Haq) (left) in November 2000 (Screenshot from a documentary film about the anti-Taliban resistance made by the Afghan Ariana Films, via Wikimedia Commons)

Notably, the US kept Massoud and his resistance at arm’s length, perhaps because they were receiving weapons from Iran, with logistical aid from Russia and the Central Asian republics. According to a Human Rights Watch report on the regional weapons trade, one Iranian shipment seized in Kyrgyzstan in 1998 contained ammunition for T-55 and T-62 tanks, antitank mines, 122mm towed howitzers and ammunition, 122mm rockets for Grad multiple launch systems, 120mm mortar shells, RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenades, hand grenades and small arms ammunition. (5) Although of Russian design, the Human Rights Watch investigators were unable to determine whether the arms and ammunition were manufactured in Russia or somewhere else.

At the time, the Taliban were being supported by Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence service (ISI), an instrument of American influence since the campaign against the Soviets in the 1980s. The ISI has often been described as a free-wheeling, rogue agency, yet it has maintained a close relationship with American intelligence and Pakistan has remained a close American ally — before, during and after President Musharraf’s military coup.

Although Massoud had cast his lot with Russia and Iran, he was no stranger to the US State Department. According to United Front veterans I interviewed, (6) Massoud met on several occasions with Robin Rafael, the American Deputy Foreign Minister for the East, between 1996 and 1998. Apparently, Commander Massoud was extremely angry after his final meeting with Rafael, who’d suggested in the meeting that his best option might be to surrender to the Taliban. At the time, Massoud’s forces had retreated into the rugged Panjshir valley, and the Taliban controlled some 95% of Afghanistan. According to the story, Massoud threw his pakul — a distinctive Afghan hat — onto the table and pointed at it, announcing that as long as he controlled a territory that big, he would never surrender. Considered arrogant by his enemies, supporters describe Massoud as an independent Afghan nationalist incapable of taking orders from foreigners. Massoud would never have allowed foreign bases on Afghan soil, according them.

Bob Woodward, in his insider account of White House deliberations following September 11th, writes that on September 13th, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet advised the President and the National Security Council that Massoud’s assassination had severely fractured the United Front, “but with the CIA [paramilitary] teams and tons of money, the Alliance could be brought together into a cohesive fighting force.”

“All right,” the President said. “Let’s go. That’s war. That’s what we’re here to win.” (7)

Tenet was right: by the time the US invaded in October, most of Massoud’s former commanders and allies were on the CIA payroll.

The Shanghai Alliance

The geopolitics of Central Asia did not begin on September 11, 2001. They were set into motion on September 9th, though. As the popular figurehead of the exiled Rabbani government, Massoud was in frequent contact with the heads of foreign states, including, it is claimed, those attending the Shanghai Five meetings. Since the Shanghai alliance has barely been mentioned in the western press, or in any books about Afghanistan or 9/11, some background on this organization is in order.

In April 1996, the Presidents of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan met for the first time in Shanghai, China to address their common concerns over border security, and the threat of Islamic fundamentalists from Afghanistan moving into Central Asia, Russia, and the western Xinjiang region of China. (8) This meeting resulted in the signing of a military agreement addressing border security among the members. (9) One year later, the five heads of state met again, signing another agreement on the mutual reduction of military forces in the border areas. (10) Beginning in 1998, the five countries held annual summit meetings, in an alliance known informally as the “Shanghai Five.” (11)

On June 15, 2001, Uzbekistan joined the group. (12) The the Declaration of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization was signed, (13) committing its members’ security organizations to cooperate to “prevent, expose and halt … three hostile forces … terrorism, separatism and extremism.” (14)

China’s concern with Central Asian “terrorism” originates in the separatist Uighur groups in its western Xinjiang region, who advocate the territory’s independence under the name of East Turkistan. The Uighurs are a muslim group populating the neighboring countries of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan as well. (15) According to Alim Seytoff, president of the Uighur American Association, under Chinese pressure, Kazakhstan, Kirgyzstan and Uzbekistan have been suppressing the Uighur dissidents in their respective countries and sending them back to China. (16) The Xinjiang region also contains China’s biggest untapped reserves of natural gas and oil. (17)

Russia, fighting its own war against Islamic separatists in Chechnya, also has strategic interests in the Central Asian republics. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have fought Islamic movements within their borders, believed to have been organized abroad. While in power from 1996-2001, the Taliban, with the help of the ISI, set up dozens of jihadi training centers in remote areas of Afghanistan. One such center, run by the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), an organization allegedly engaging in terrorist bombings, and having had clashes with Uzbek security forces, was believed to be training militants from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang, China. (18) Afghanistan was also the home of Osama Bin Laden‘s al Qaeda organization, training Arabs from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Somalia, and Algeria, (19) seen by Russia as a serious threat to regional stability.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev, Chinese President Jiang Zemin, Kyrgyz President Askar Akayev, and Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, at one time the leaders of the Shanghai Five. (Source: CC BY 4.0)

In June of 2002, the SCO heads of state met again in St. Petersburg, Russia, to sign the Charter for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (20) They also agreed to establish an anti-terrorism agency in the region. (21) In its meeting last May in Moscow, the SCO decided to set up a permanent secretariat based in Beijing, and locate the anti-terror center in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. The leaders set January 1, 2004, as the deadline for the SCO to function with a permanent secretariat in Beijing. (22) The SCO’s joint statement also declared that the “war against terrorism should be pursued on the basis of international law” – a clear reference to US military action in Iraq. (23)

The SCO also held meetings last week in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, announcing that the new anti-terror center, called the SCO Regional Antiterrorism Structure, would be located in Tashkent instead of Bishkek. (24) American policy analysts expect the anti-terror center to function as a joint coordinating center for the SCO and the Commonwealth of Independent States, an association of former Soviet republics formed after the dissolution of the USSR. (25)

This is not the only indication of increased Sino-Russian military cooperation. Earlier this year, Russia and China signed the “Treaty on Good-Neighborly Relations, Friendship and Cooperation,” providing for increased Russian arms sales to China and the training of Chinese officers in Russian military schools. (26) Beginning August 6, 2003 the original Shanghai Five, including China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan held their first joint anti-terror military exercises, called Cooperation 2003, in Kazakhstan and China, (27) involving about 1000 personnel. (28)

Uzbekistan did not participate in the exercises. Uzbekistan was designated by Washington as a “strategic partner” in 1995, (29) and in the spring of this year, signed an agreement with the US providing for the use of military bases and facilities, and the stationing of US troops in Uzbekistan. (30) Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan all hosted US forces during the Afghan war. (31)

It also appears that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization may be expanding soon to include several countries in Southeast Asia. After meeting last month with Wu Bangguo, chairman of the standing committee of the National People’s Congress of China, Philippine Speaker Jose de Venecia Jr. announced that the Philippines would be joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, along with Indonesia and Malaysia. Last year, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia made a separate agreement to exchange intelligence and conduct joint border patrols and training programs. (32) Later, Cambodia and Thailand signed this accord. (33)

The next meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization will be held on September 23rd of this year in Beijing. Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, Kazakh Prime Minister Daniyal Akhmetov, Kyrgyz Prime Minister Nikolai Tanayev, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, Tajik Prime Minister AkilAkilov and Uzbek Prime Minister Utkur Sultanov are all expected to attend. (34) Chinese news agencies have not confirmed whether Philippine or other Southeast Asian leaders will be invited.

Massoud and the SCO

What makes all of this so interesting is that it provides an undeniable motive for the United States to have launched its own “war on terrorism” in Afghanistan: to establish military dominance in the region in the face of an embryonic Sino-Russian military alliance.

The United Front veterans I met were certain that Ahmad Shah Massood attended at least one of the early “Shanghai Five” meetings, held in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, in June of 2000. He might have attended others, they said, but were certain he attended that meeting at least. Whatever Commander Massoud said in the meeting is not known — the meetings were held behind closed doors — but his attendance speaks for itself.

All of the above is meant to explain why the United States attacked Afghanistan. Was oil a motive? Probably so, there’s no debating the importance of oil in the region. But I would argue that the larger issue was the possibility of Sino-Russian control over it. What about the attacks on our embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, and the attack on the USS Cole? Also reasons to attack bin Laden’s organization in Afghanistan, no doubt. But none of this is really related to the attacks in New York and Washington used to justify the invasion of Afghanistan. As far as I know, there is no evidence linking bin Laden or the Taliban to those attacks. The Taliban were disliked for other reasons, including their repression of Afghan women.

The “Sino-Russian” alliance, barely mentioned in the western press, must have been taken seriously by the US government, though. To me it seems to have been, and still is, the most serious threat to American influence in Central Asia since the fall of the Soviets. Enough to justify the our taking the initiative and launching a pre-emptive war on terrorism ourselves? No doubt. Enough to assassinate the legendary Mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, who drew his inspiration, he believed, directly from God? In all likihood, this is one murder that will never be solved.

*

Notes

1. A detailed account of Massood’s assassination can be found in The Lion’s Grave: Dispatches from Afghanistan, by Jon Lee Anderson.

2. For one example, see “Afghan Leaders Pay Tribute to Guerrilla Leader,” The Washington Post, Sept. 10, 2003.

3. “Major Terror Trial in Belgium,” CNN.com, May 21, 2003.

4. “Afghan Leaders Pay Tribute to Guerrilla Leader,” op cit, Sept. 10, 2003.

5. “Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity: The Role of Pakistan, Russian and Iran in Fueling the Civil War,” Human Rights Watch, July 2001. http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan2/

6. Interviews with United Front veterans in Kabul, June 2003. The veterans did not hold government jobs or owe allegiance to any Northern Alliance commanders working with the US, or to any regional commanders now in power.

7. Bush at War, by Bob Woodward, 2002, p. 51.

8. “Preventing Another ‘Great Game’ in Central Asia,” Center for Defense Information, January 2001, http://www.cdi.org/asia/fa011201.htm .

9. “Shanghai Cooperation Organization develops steadily,” Xinhua, Sept 4, 2003 http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2003-09/04/content_1063025.htm

10. Id.

11. “U.S. Intervention in Afghanistan: Implications for Central Asia ,” by Robert M. Cutler, Foreign Policy in Focus, November 21, 2001. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p6

12. “`Shanghai Five’ expands to combat Islamic radicals,” by John Daly, Janes Terrorism and Security Monitor, 19 July 2001. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p7

13. Xinhua, op cit, Sept 4, 2003

14. “Bloc Including China, Russia Challenges U.S. in Central Asia: Members Agree to Combat Militant Islamic Groups And Share Intelligence,” by Andrew Higgins, The Wall Street Journal, 06/18/2001. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p8

15. Id.

16. “China’s Report on Xinjiang Region Questioned,” by Stephanie Mann, The Voice of America, 29 May 2003. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p4

17. Janes Terrorism and Security Monitor, op cit, 19 July 2001.

18. “A Shanghai forum with India?” by M.K. Dhar, The Pioneer, July 19, 2000. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p9

19. Id.

20. Xinhua, op cit, Sept 4, 2003

21. Id.

22. “SCO warned about unilateral action,” Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting News Network, 5/29/2003. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p5

23. “Central Asia wary of US’s widening reach. Grouping sees US interests as posing challenges; will boost security and economic cooperation,” by David Hsieh, The Straits Times, June 14, 2003. http://www.ratical.org/ratville/CAH/ShanghaiCO.html#p1

24. “Uzbekistan: Foreign Ministers Of Shanghai Cooperation Organization Converge In Tashkent,” by Charles Carlson, Radio Free Europe , Sept. 5, 2003 http://www.rferl.org/nca/features/2003/09/05092003174355.asp

25. Foreign Policy in Focus, op cit, November 21, 2001.

26. Id.

27. “Foreign Observers Attend Chinese War Games for the First Time,” The People’s Daily, August 26, 2003. http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200308/26/eng20030826_123063.shtml

28. Xinhua, op cit, Sept 4, 2003

29. Foreign Policy in Focus, op cit, November 21, 2001.

30. Id.

31. The Straits Times, op cit, June 14, 2003.

32. “RP, China to Push Formation of Asian Anti-Terror Alliance,” by Paolo Romero, STAR, September 1, 2003. http://www.newsflash.org/2003/05/hl/hl018695.htm

33. “R.P., China push new pact vs terrorism,” ABS-CBN News, August 31, 2003. http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/abs_news_body.asp?section=National&oid=32145

34. “PMs of SCO to hold second summit,” English Eastday (China) Sept. 11, 2003 http://english.eastday.com/epublish/gb/paper1/1022/class000100004/hwz159535.htm