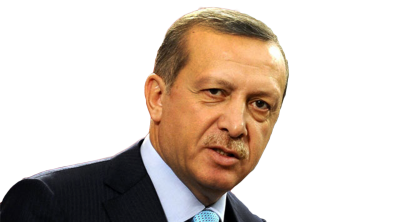

Turkey’s “Democratic Dictatorship”: After Failed Coup, Erdoğan Cracks Down

Faced with an attempt to overthrow his government, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan described the coup as “a gift from God” – and wasted no time in exploiting it to further entrench his authoritarian regime.

Turkish government broadcaster TRT was seized by a group of military officers calling themselves the “Peace in the Country Council” on July 15, who announced that they had taken over the country. Within 24 hours, the coup attempt had failed. Erdoğan responded by calling his supporters to the streets. Once his government’s survival was guaranteed, it quickly became clear that one coup’s failure was becoming another’s success.

The authoritarian president has been seeking to concentrate more power in his own hands. However, his ambitions were frustrated last year by the success of the left-wing Kurdish-led People’s Democratic Party (HDP) in elections. This blocked plans by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) to change the constitution, which required winning two-thirds of parliamentary seats.

Fascist mobs, with support from the police, attacked neighbourhoods populated by Kurds, the Alevi religious minority, other minorities and leftists. Istanbul, July 16. Photo: Sendika10.org.

Erdoğan’s use of the failed coup to launch one of his own was borne out by scenes on July 16 and following days. Mobs of Erdoğan’s right-wing Islamist supporters beat and lynched soldiers surrendering after the coup and launched attacks on neighbourhoods inhabited by minorities and supporters of the left. It has been further borne out by a huge purge that has targeted not just the military, judiciary and civil service, but also the media, academia and civil society. The purge deepened pre-existing moves by Erdoğan to control these institutions.

Unravelling the Coup

The HDP opposed the coup, as did the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and other Kurdish groups that have been mounting armed resistance against the Turkish state’s brutal military onslaught over the past year.

HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş said on July 19th:

Kurdish guerillas could have taken advantage of this attempt and seized many cities, but this would be playing into the hands of the pro-coup mindset.

[The] Kurdish movement, by not making a choice between the two pro-coup mindsets, maintained a dignified stance that insists on the democracy struggle of the peoples. However, people like Erdoğan do not have the capacity to understand this dignified stance.

Both the left and the movement of the long oppressed Kurdish minority (which makes up about 20 per cent of Turkey’s population) warned that whoever was the victor in fighting between coup-makers and Erdoğan’s forces, democracy and the people would lose.

It is not clear who was behind the failed coup. There has been some speculation that the whole thing was Erdoğan’s “Reichstag fire” – a faked coup to rally support for the president and justify further restrictions on democracy. This conspiracy theory is not as outlandish as it might seem, given the Byzantine workings of the Turkish state. Erdoğan’s inner circle has worked in close cooperation with the military in the past year’s war against the Kurdish people and in the sponsorship of armed groups in the Syrian Civil War.

The theory has been fuelled by incongruities in the events on the night of the coup. These include pro-coup air force jets intercepting, but not shooting down Erdoğan’s plane when he returned to the largest city, Istanbul, and the failure of the coup plotters to take over pro-government commercial media outlets. This allowed Erdoğan to rally support in an interview conducted over FaceTime.

However, these facts could also be explained by incompetence on the part of the coup plotters, less support than anticipated from the military or the attempted coup being executed prematurely after being discovered by the intelligence service, the MIT.

Furthermore, as left-wing journalist Ali Ergin Demirhan pointed out on Sendika10.org on July 17th: “Given that Turkey’s is a NATO army, it is well-nigh impossible for the army to conduct a successful coup against the wishes of the U.S. and EU (that is, NATO).” Support from the U.S. and EU was not forthcoming.

The “Reichstag Fire” theory was boosted when Erdoğan blamed the “parallel state” for the coup – code in AKP jargon for the followers of Fethullah Gülen, a U.S.-based Islamic preacher who was an ally of Erdoğan until 2014. The AKP government had allowed Gülen’s supporters to infiltrate the institutions of Turkish state. The aim was to displace supporters of “Kemalism”, the right-wing secular ethnic nationalist ideology of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who founded the Turkish Republic in the 1920s.

In 2014, Gülenists in the judiciary tried to bring corruption charges against members of Erdoğan’s inner circle. Since then, the AKP has carried out several purges against Gülenists in the state apparatus.

However, a July 21 statement by the Brussels-based Kurdistan National Congress explained:

It is important to specify that this coup was not undertaken by Gülenists.

Due to the conflict between the AKP and the Gülenists, sympathizers of Gülen may have taken part in the coup attempt. But by saying ‘the Gülenists attempted the coup’, AKP-Erdoğan are trying to create a platform on which they can suppress Gülen’s supporters even more.

By labelling the coup as Gülenists (who many people see as worse and more reactionary than them), they are hoping to rally support in order to take revenge on the putschists. In other words, they are trying to kill two birds with one stone.

It is evident that this attempt was backed by a large part of the army. If they had planned and executed it more professionally, it may have succeeded.

In this regard, it cannot be said that it was undertaken by Gülenists or a minority; there isn’t enough of a Gülenists presence in the army to pull off a coup.

There has also been speculation that Kemalists were behind the coup. Until the 1990s, Kemalism was dominant in the Turkish state. When its predecessors first rose to power in the ’90s, the AKP’s Islamism was a challenge to the Kemalist establishment. Kemalist ideology includes an extreme form of secularism based on the French ideology of laïcité, which, among other things, bans people wearing Islamic clothes from higher education and public sector employment.

For much of its existence, the Turkish republic has been under military rule. The armed forces have traditionally seen themselves as the guardians of the state’s Kemalist ideology. Conflict between the AKP and Kemalism has often manifested as conflict between the government and the army, resulting in large-scale purges in 2009 and 2013. This ironically benefited Gülen’s supporters. It is likely that Kemalists were involved in the failed coup. However, the two large Kemalist parties, the MHP and CHP, both opposed the coup.

Ethnic Minorities

For much of his rule, Erdoğan has been at loggerheads with the Kemalists, but in the past year there has been a rapprochement based on the violent oppression of common enemies. Primarily, this has been the Kurds. Extreme ethnic nationalism was always central to Kemalist ideology. As Turkey’s largest minority, the Kurds were subjected to forced assimilation from the Turkish Republic’s birth in the 1920s. (The other two main minorities – Armenians and Greeks – were ethnically cleansed shortly before and during the republic’s birth.)

The state not only banned Kurdish culture, Kurdish names and the Kurdish language, it even banned the letters “q”, “w” and “x” because these exist in Kurdish but not Turkish. Thousands of people were forcibly moved to cities in a bid to erase their ethnic identity.

After the PKK initiated armed resistance in 1984, about 30,000 Kurds were slaughtered by the military and paramilitaries. The Humanitarian Law Project documented 18,000 extrajudicial executions of Kurdish civilians.

When Erdoğan was first elected as prime minister in 2003, his government took a more liberal approach toward the Kurds. The Kurdish language remained banned from use for official purposes, but speaking it was no longer a crime and the letters “q”, “w” and “x” were legalized. The PKK remained illegal, and its leader Abdullah Öcalan remained imprisoned in an island dungeon. But the regime held sporadic talks with the PKK and Öcalan, culminating in the 2013 peace process.

The AKP regime was initially more liberal than its Kemalist predecessors in other respects. However, it was also fiercely neoliberal. In 2013, protests against the privatization of public space in Istanbul’s Gezi Park mushroomed into a nationwide youth-led movement for economic opportunities, civil liberties and against increasing moves by Erdoğan to concentrate power in his own hands.

This “Gezi Park” movement involved Turkey’s large, highly militant but perennially factionalized ‘old left’. Most significantly, though, it sparked the creation of a ‘new left’, similar to anti-neoliberal movements erupting at the same time in public squares in southern Europe and incorporating the feminist, LGBTI, environmentalist and other movements.

The HDP managed to unite most of the old and new left with the Kurdish movement into an electoral force strong enough to deny the AKP a two thirds majority in elections in July last year. In doing so, the HDP secured significant parliamentary representation for forces threatening to both Turkey’s Islamist and Kemalist elites.

Erdoğan’s response was to call a second election, restart the war against the Kurds and launch violent crackdowns against the opposition. There were mass arrests of academics, closure of newspapers and the flattening of Kurdish towns and cities. The regime also used mob violence against leftists, Kurds, religious minorities and those seen as non-conformist.

Significantly, Islamist AKP supporters stood shoulder-to-shoulder with secular fascist “Grey Wolves” affiliated to the Kemalist MHP in this mob violence. Despite this, the second election, on November 1, still failed to give the AKP its two thirds majority or keep the HDP out of parliament.

The renewed war against the Kurds put the armed forces at the centre of politics again. Why a section of the armed forces turned against the regime is unclear. The air force most clearly sided with the coup, while the MIT, the Special Forces Command and the Turkish National Police most clearly opposed it. The bulk of army land forces stayed out of the fighting, leading to speculation that they may be biding their time for another coup attempt.

It is possible that Erdoğan’s foreign policy may be a factor. When the civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, Erdoğan gave support to mainly Islamist armed groups fighting the Syrian dictator, Bashar Assad, hoping to gain influence over a post-Assad regime. Some groups were supplied with arms and logistical support, while others were directly created and run by the MIT. The extent of Turkish involvement in Syria grew and its objectives changed with the rise of the revolution in Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) in 2012. In Rojava, a left-wing movement led by Kurdish forces ideologically allied to the PKK had become a key player in Syria’s conflict.

With crushing Rojava the main objective, and various Turkish-backed armed groups failing to do so, Turkish support went to the groups that Erdoğan viewed as most likely to be able to accomplish this: first the al Qaeda-aligned Nusra Front, then ISIS. Western governments have consistently downplayed its NATO ally’s support for ISIS – the West’s official arch-enemy. But at certain times, Turkey’s relationship with the West was strained by the constant traffic of jihadis through Turkey, on the one hand, and the U.S.’s tactical alliance with the Rojava-based forces on the other.

Turkey’s air force shot down a Russian military plane last November in a move intended to force the U.S. to side more closely with Turkey. But all it achieved was a hostile relationship with Russia.

Furthermore, Turkey seems to have suffered blowback from its involvement in Syria in the form of ISIS terrorism in Turkey. Initial ISIS attacks in Turkey suggested the relationship between the AKP and ISIS remained strong. The June 5 attack in Diyarbakir last year, which killed four people, and the October 10 attack in Ankara, which killed more than 100, targeted the HDP and were straight out electoral violence on behalf of the AKP.

Last year’s July 20 attack in Suruç, which killed 33 left-wing youth travelling to Kobanê to help reconstruct the iconic ISIS-ravaged Rojava town, also eliminated militant opponents of the government. There is evidence the police enabled all these attacks.

However, since then, ISIS attacks in Turkey have become more indiscriminate, targeting random civilians and tourists. The reason might be that as ISIS failed to crush Rojava, Turkey has given more support to other armed proxies in Syria.

Suspending Democracy

Just before the failed coup, the Erdoğan government normalized relations with Russia and with Israel. Relations with Israel had become strained after the Israeli murder of Turkish activists attempting to break the blockade of Gaza in 2010. There were also reported moves toward normalising relations with Assad’s ally, Iran, and even Assad himself.

Whether the failed coup-makers were opposed to this policy shift, or opposed to Erdoğan’s previous policy in Syria is a matter for speculation. Interestingly, Iran was one of the first countries to condemn the coup, even before it was certain it had failed. What is certain is that whether the coup succeeded or failed, the result would be the same inside Turkey – greater violence and oppression.

The coup’s failure has strengthened Erdoğan and the Islamist wing of the Turkish state and political elite. On July 16, pro-Erdoğan mobs beheaded and beat to death captured soldiers – many of whom were conscripts who were unaware they were taking part in a coup, having been told by their commanders that they were responding to a terrorism alert in Istanbul. Since then these mobs have, with support from the police, attacked neighbourhoods that are populated by Kurds, the Alevi religious minority, other minorities and leftists in Istanbul, Ankara and other cities.

Syrian refugees have also been targeted, suggesting ethnic nationalism, as well as Islamism, has fuelled the mob violence. However, Sendeka10.org reported on July 17 that residents of these communities militantly resisted the mobs, in some cases successfully.

A purge of the armed forces is understandable after a failed coup, but Erdoğan is using the pretext to achieve the concentration of power he has been striving for. About 7000 people, civilians as well as soldiers, have been arrested. Journalists have had their credentials revoked and TV stations have had their licenses taken away. About 15,200 education workers and more than 2800 members of the judiciary have been sacked.

On July 21, Erdoğan declared a state of emergency and suspended the application of the European Convention on Human Rights.

HDP spokesperson Ayhan Bilgen responded: “If the coup was successful they would have declared a state of emergency. The AKP government who claim that they pushed back the coup and protected democracy now declares a state of emergency and does what would have happened.”

JINHA Women’s News Agency responded that Kurds had been living under a state of emergency for the past 36 years. But the response of the Kurdish movement, the left and Turkey’s militant working class communities has shown that resistance will continue even in the face of greater repression.

As Ali Ergin Demirhan put it: “Ultimately, it behoves everyone who says no to both a coup and an Islamist dictatorship to remember the third option presented at Gezi as a model for resisting for democracy.” •

Tony Iltis writes for Green Left Weekly, where this article first appeared.