Turkey and its Kurds at War: Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Personal Quest for Survival

The Kurdish town of Cizre, a settlement with a population of approximately 150 thousand souls in Southeastern Turkey, is now under siege by the Turkish armed forces and the so-called “special operation force” of the police for a second time, after a previous one-week long siege was lifted for an interlude of two days. Around-the-clock curfew is accompanied by power cuts and the interruption of all means of communication including mobile telephones and the Internet. The evidence that came out when the first round of siege was lifted attests to a terrible human drama.

Over 30 civilians are dead, ranging from a 35-day old infant to a 75-year old man. Before the siege was lifted, government sources claimed that security forces had killed more than a dozen fighters of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish guerrilla army, denying any civilian deaths. How the baby and the old man could have contributed to the fight of the PKK remains a mystery unexplored by government spokespeople after the facts have come to light.

The plight of Cizre is just the latest and most dramatic episode in a war that the Turkish state has been waging against its own citizens in the Kurdish regions of the country since late July. Basing itself on the excuse of the Suruç massacre on 20th July, in which 32 young Turkish leftists holding a press conference to express their solidarity with the people of Kobane, a city that is part of the Kurdish entity of Rojava within the frontiers of Syria, were killed by a suicide attack, in all probability the making of ISIL, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the Turkish government of the AKP, the party of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, started a war… not against ISIL, but against the PKK and the Kurdish people! It is true that the AKP government has made a concession to the U.S. by finally allowing it to use the Incirlik air base in Turkey to attack ISIL and, somewhat later, has also agreed to participate itself in those air raids. This was, however, simply a manoeuvre to consolidate its flank while embarking on a wholesale attack on the Kurdish movement, avoiding tension with the U.S. while engaging in a difficult military enterprise.

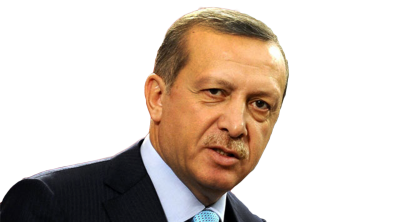

Erdogan’s selfie.

Turkey’s War against the PKK, and the Kurdish People

Turkey’s war is not only against the PKK, but the Kurdish people as a whole. It has taken at least three different forms. The first is the military conflict proper between the Turkish armed forces and the PKK. This has so far taken the form of bombardments by the Turkish air force of PKK camps in Northern Iraq, on the territory of the Kurdish Regional Government led by Barzani, a close American and Turkish ally. The PKK has reciprocated by killing Turkish soldiers and police officers by the day. However, the two most spectacular instances of such raids came within forty-eight hours in early September, when the PKK blew up 16 soldiers in the southeast of the country and subsequently 13 police officers in the northeast. The very long geographical distance between the locations of the two incidents, as well as the heavy losses suffered by the Turkish forces, were meant to show the country that the PKK is a formidable force.

The second form the war has taken is the effort on the part of the state to pacify the flashpoints in the cities and towns of Turkish Kurdistan. Since early 2013, a process of negotiations between the government and the PKK, called the “solution process” was going on. However, not all in the Kurdish movement are happy with this process. Abdullah Ocalan, the historic leader of the PKK, held in captivity since 1999, is the architect of the process. Yet there are other actors on the scene. The official ones are the PKK based in Northern Iraq and the HDP, the People’s Democratic Party, an avatar of the parliamentary Kurdish movement that has now joined forces with a host of Turkish socialist parties and movements. Among these three, Ocalan is the most flexible while the PKK projects a more intransigent image. However, there is a fourth actor on the scene, called the YDG-H, which is usually presented as the youth wing of the PKK, but really has lately acted as a quasi-independent force. It stands to the extreme left of the movement and despite swearing unswerving allegiance to Ocalan, is patently critical vis-a-vis the “solution process”. It is they who organise whole neighbourhoods in many Kurdish cities and towns and make these neighbourhoods inaccessible to Turkish security forces by digging ditches and trenches and defending these with arms in hand when needed. The population at large may not agree with their methods, but sides with them against governmental forces during periods of conflagration when push comes to shove.

Hence the attacks on a series of Kurdish towns as part of the ongoing war, towns such as Silopi, Varto, Yuksekova, Silvan, and now, most dramatically, Cizre, the most prominent stronghold of the YDG-H. (These and all other settlements in Turkish Kurdistan have original Kurdish names that were replaced forcibly by Turkish names in republican times, but citing these, important as that may be in the local context, would not mean much to an English-speaking audience.) In contradistinction to the first form that the war has taken, a conflict between two armed forces, this one is a war waged against the civilian population. Since almost the entire population stands with the youth, what seems to be an assault on a militia force is necessarily transformed into a war on the whole people. The author of these lines only weeks ago visited, for purposes of solidarity, Silvan, a town near Diyarbakir, immediately in the aftermath of a similar assault staged by security forces and witnessed with his own eyes the ravage wrought on the whole town as a result.

The third form is the potential threat of veritable civil war involving civilians from both sides. This threat is contained in the continuous harping on the nationalistic, even chauvinistic, emotions that exist within major sections of the Turkish population of the country, not only on the part of forces close to Erdogan and the AKP, but equally by what is known in the West as the “Grey Wolves” of the Nationalist Action Party, the more traditional fascist movement of Turkey, the third biggest party of the Turkish bourgeoisie (the second force being the Republican People’s Party, the party of Kemalist origin that now poses as social democratic). It was the “Grey Wolves” that descended on the streets on the night of 8th September in reaction to the two spectacular PKK attacks referred to above. More than 140 HDP locales were attacked, many set ablaze, ordinary Kurds were hunted on the streets of the cities and towns of the Turkish-dominated western parts of the country, intercity buses stopped and stoned, and Kurdish seasonal workers attacked collectively, their houses and cars burnt down, and they themselves driven away en masse. Now, although the Kurds are a minority in the cities of the west, they are quite a sizeable minority in many of these and, moreover, they are extremely politicised communities with considerable martial skills. If they did not respond in kind, this was out of self-restraint. This means that in future the situation may get out of hand and the war may degenerate into an ethnic civil war that may take extremely bloody forms.

The Dynamics behind the War

In order to stop this war, one needs to identify the dynamics that lies behind its eruption. Unfortunately, the Kurdish movement, long under the influence of the liberal intelligentsia, keeps repeating that what is needed is a return to the status quo ante, i.e. to the “solution process” at the stage where it was left off. This ignores the fact that there are very definite forces at play that have led to this war and these should be countered and defeated before peace or at least a cease-fire can be re-established. These forces are of different kinds, some deriving from the political conjuncture while others are more structural in nature.

The overbearing reason, eclipsing all others in importance, is that which derives from the political interests of Tayyip Erdogan. In an earlier article (“The strategic defeat of Recep Tayyip Erdogan”) published on this web site after the elections of 7th June in Turkey, we pointed out that the pitiful results obtained by Erdogan’s party, the AKP, which lost 10 percentage points of the popular vote, as well as its parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002, is simply a registration of the earlier strategic defeat of this politician at the hands of the masses, first in the popular revolt that was triggered by the Gezi Park incident in June 2013 and subsequently during the serhildan (intifada) in October 2014 staged by the Kurdish people in reaction to his callous attitude to the plight of Kobane when it was attacked by ISIL. The election results were a double catastrophe for Erdogan. On the one hand, he needs a two- thirds majority in parliament if he is to amend the constitution so as to convert the Turkish political system into a presidential one, giving him the powers to control the whole political process, powers that he now lacks under the current parliamentary setup in which the office of the president of the republic he now occupies is rather ceremonial in nature. On the other hand, the fact that the AKP has not even been able to hold on to its parliamentary majority may possibly open up the floodgates of investigation into the very serious and well-documented cases of corruption in which not only his ministers but he himself was involved. Most commentators dwell on his ambition regarding the acquisition of the mantle of executive president. We think that it is much more an urgent need of avoiding the opening up of the corruption files by a parliament in which the AKP now finds itself a minority. If the other parties could get their act together and open those files, Erdogan may find himself facing the precipice, with the outcome being his conviction (the legal details need not detain us here).

Since it was the success of the HDP of overcoming the extremely high electoral threshold of 10 per cent that directly led to the failure of the AKP to obtain a parliamentary majority, Erdogan and his cohort have placed their hopes in raising Turkish chauvinism and presenting the HDP not as a messenger of peace, but as a force that supports the “terrorism” of the PKK, thereby causing the party to fall below the critical 10 per cent threshold in early elections, to be held on 1st November. Hence, the war is, first and foremost, a war of survival for Erdogan. There have been imperialist wars in history and anti-colonialist ones. This is the first egoist war ever!

This is what we wrote immediately after the elections on this web site:

The erroneous policy of the left provided a breathing space for Erdogan that gave him the possibility of climbing to the presidency. Now the AKP cannot form a government on its own, but Erdogan will still be holding the reins of power. He will use every inch of the space he has thus conquered to cling on to power and may even resort to war against the Kurds or in the Middle East at large for that purpose. In politics every mistake has a price.

It need not even to be pointed that the prediction contained in that paragraph has unfortunately come true. As for the mistake we were talking about there, this referred to the fact of not having tried to bring down Erdogan when it was possible to do so. Here, the major blame lies with the Kurdish movement. Had they moved in tandem with the popular revolt triggered by Gezi in 2013, Erdogan would almost certainly have fallen from power, so strong is the capacity of the Kurdish movement to organise the masses especially in Diyarbakir. It is sad to note that the suffering of the Kurdish people at the hands of atrocious attacks by Turkish security forces is, at least partially, a product of the errors of the Kurdish movement.

There are, of course, more long-standing and structural factors that push Turkey to wage war on the Kurdish movement. One has already been touched upon. The radical wing of the Kurdish movement, embodied most visibly in the youth movement, is against the “solution process” unless Ocalan has been previously released from prison. (A striking slogan that the youth displayed during a mammoth demonstration in 2013 read: “A peace with the serok(Ocalan’s title in the movement) captive is muddle-headed”.) The youth have many supporters, albeit less fiery than they themselves, and almost the whole population tends toward that kind of intransigent position when things get rough, as they frequently do. The serhildan of October 2014 scared the ruling circles immensely and posed on the agenda the liquidation of these pockets of (armed) urban resistance, which, as opposed to the rural guerrilla, would pose an immediate threat in case a new serhildan erupted. So the present war may also be considered as an attempt on the part of the Turkish state to do away with these pockets of resistance.

The other major factor that leads to friction between the state and the PKK is, by the sheer objective fact of its existence, Rojava, the autonomous Kurdish entity south of the Turkish-Syrian border. Kurdish autonomy or, a fortiori, independence in other parts of Kurdistan, i.e. in Iraq, Iran or Syria, has always loomed as a threat to the Turkish ruling classes, if only because it could act as an example to Turkey’s Kurds. Within the first 15 years of the 21st century, first Iraqi Kurdistan, then Syrian Kurdistan have attained autonomy. At first deeply disturbed by the creation of Iraqi Kurdistan under Barzani as an autonomous region, Turkey finally came to terms with it and is now becoming the dominant power both economically and politically over the Kurdish Regional Government. The Turkish bourgeoisie is filled with expectations of benefits to flow from the oil of the Kirkouk region. Rojava, though, is a different matter. Barzani is a staunch ally, even a protégé, of the U.S. and lately of Turkey itself. Rojava has been set up under a leadership organically linked to the PKK! The AKP government has always made it clear that Turkey will not come to terms with a PKK-dominated political entity to its south. So Rojava has been, all throughout its three-year period of existence, a thorn on the side of the “solution process”.

Whither Turkey, Whither the Kurdish Question?

The last point about Rojava suggests that the future of the Kurdish question of Turkey and, indeed, of Turkey itself is intimately tied up with prospects for Syria. As most readers will be aware, Erdogan and his AKP are major actors in the ordeal that Syria has been going through since 2011. Erdogan, alongside Saudi Arabia and Qatar, has fanned the flames of hatred and war in Syria between the Sunni and the Alevi (the Alevi being a minority denomination in Islam, closer to the Shia than the Sunni.) This is part of a larger design, whereby Erdogan strives to assume the leadership of the Sunni masses of the Middle East and return to Turkey the glory of its Ottoman past. That is one reason why the AKP government supported ISIL until very recently and continues to support other Islamist groups fighting against the Assad regime.

The situation born of the deal between the U.S. and Turkey in late July, whereby Turkey opened the Incirlik base to U.S. air raids on ISIL in return for American license for its attacks on the PKK, bears a dialectical contradiction that may in time suck Turkey into a ground war in Syria. In its fight against ISIL, the U.S. relies, among others, on the armed forces of Rojava as ground troops. Turkey’s efforts, on the other hand, aim to keep these same forces of Rojava out of certain regions south of the Turkish-Syrian border, regions where Turkey wishes to establish so-called “secure zones”. However, the U.S. needs the forces of Rojava to fight ISIL on the ground. It seems the only way Turkey can talk the U.S. out of collaborating with Rojava militarily is to send ground troops itself to establish what it would consider secure zones.

This prospect deriving from the contradictions of the military alliance between the U.S. and Turkey is complemented by the infernal logic of Erdogan’s quest for survival: should the AKP fail to obtain a majority in parliament in the near future, Erdogan needs to suspend the normal functioning of the system, which would best be done by resorting to an extension of the war to Syria or even the Middle East at large. It is only the first half of our prediction that has materialised for the moment (“Erdogan” we were saying in the passage quoted above, “may even resort to war against the Kurds or in the Middle East at large for that purpose”). It would not be surprising to see the second half come true as well.

There are, of course, certain counteracting tendencies that may come to play their part. One is the possibility that one of the major actors, Ocalan, silent so far since the elections and the eruption of the war, speaks out to create a kind of thaw. The coming Eid al-Adha, the great religious festival of the Islamic world, may be an opportune moment for him to open a new chapter in the “solution process”. It should not be forgotten that despite the ferocity of the war, neither the AKP, nor Erdogan, nor yet the Kurdish side has totally thrown out the possibility of a new beginning. Erdogan himself has explicitly said that the “solution process” is in the deep freezer (and not dead, as the unfolding war may lead one to think). It is obvious that as soon as he finds himself on safer ground, he may willingly go back to the status quo ante. This would be the reactionary exit from the present impasse. Erdogan is a malediction for Turkey and the Middle East and the longer he remains at the helm of this country, the more trouble will be brewing for the peoples of the region.

The progressive exit would of course require the defeat of Erdogan, hopefully leading to his ouster from office and conviction for his crimes. The conditions for this are gathering. Already the succession of mass struggles in Turkey in the recent period, the Gezi popular revolt (2013), the Kobani serhildan (2014), and the metalworkers’ strike (2015), following upon each other’s heels within the space of a mere two years, demonstrates that this is a society full of social groups ready to vent their anger. On top of this, Erdogan has lost credibility, as we have been emphasizing since 2013, in the eyes of his erstwhile allies, the U.S. and the European Union, as well as the liberals of Turkey, the Gulen fraternity, and many sections of the capitalist class. Now he is losing more and more the support of large sections of his party. Former president of the republic Abdullah Gul, another founding leader of the AKP, is waiting in the wings to take over the party at the right moment. The party convention that is gathering these days will not yet bring to the surface the deep fractures that run through the AKP, but contradictions are maturing there as well.

If the positive outcome holds, it will of course make a great difference whether it is the bourgeois opposition headed by Gul and the two bourgeois parties, social democratic and fascist, or even the army, that removes Erdogan or whether it is the masses that do the job, headed hopefully by the working class, which now seems back in action after a long slumber. It is our hope and aim to make this latter solution prevail. •

Sungur Savran is based in Istanbul and is one of the editors of the newspaper Gercek (Truth) and the theoretical journal Devrimci Marksizm (Revolutionary Marxism), both published in Turkish, and of the web site RedMed.