Trump’s Twitter Blocking Violates First Amendment, Court Rules

The "interactive space" around Trump tweets is a public forum, judge rules.

A federal judge ruled on Wednesday that Donald Trump‘s use of the Twitter block button violated the First Amendment. The ruling has implications for any government official—federal, state, or local—who uses Twitter or other social media platforms to communicate with the public.

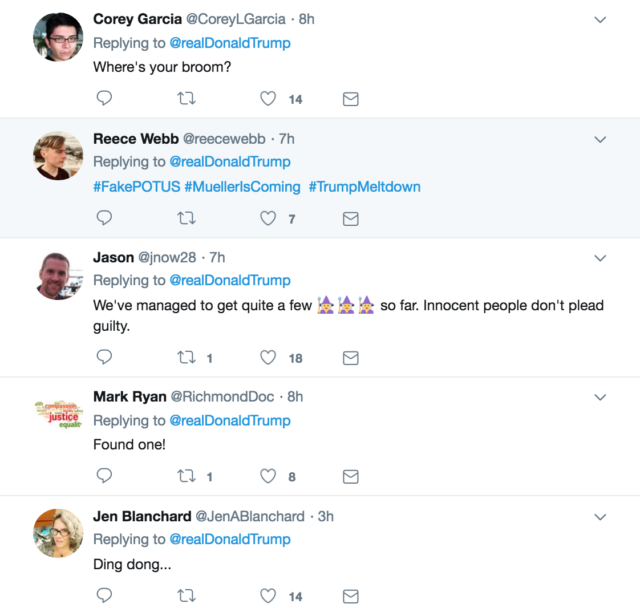

The block button is a key weapon in Twitter’s war against trolling and harassment, and Trump has used it since long before he was president. But last year, a group of Twitter users who had been blocked by Trump’s @realDonaldTrump account sued, arguing that the use of the feature by a public official violates the First Amendment.

The main effect of blocking someone is that that person’s tweets no longer show up in the blocker’s timeline. No one disputes that Trump has the right to do that if he wants. But blocking someone also works in the other direction: if Trump blocks another user, that user can’t see Trump’s tweets and (as a consequence) can’t reply to them. And that, ruled Naomi Buchwald, a New York Federal judge, raises a constitutional problem.

How a presidential tweet is like a public park

These Twitter users are participating in a constitutionally protected public forum, a federal judge has ruled.

The courts have long held that if the government creates a “public forum”—like a park, lecture hall, or street corner—that it must make the forum available to all speakers, regardless of their viewpoint. A city government can’t say that only Republicans, Christians, or vegetarians are allowed to hold rallies in the town square, and it can’t blacklist activists with a history of criticizing the mayor.

Last year, a federal judge applied this same reasoning to a Virginia politician’s Facebook page. The court held that the official’s Facebook page constituted a public forum and she had therefore violated the First Amendment when she blocked a critical constituent from commenting on it.

The Trump case is a little bit different because Twitter doesn’t give anyone the ability to post comments directly on Trump’s Twitter page. However, if you click on a Donald Trump tweet, you’ll see a long list of replies to that tweet listed underneath.

If Donald Trump blocks someone, that person loses the opportunity to reply to Trump tweets and have their tweet show up underneath them. They also lose the ability to retweet Trump tweets.

Buchwald’s ruling concludes that the “interactive space for replies and retweets” surrounding each Donald Trump tweet should be considered a public forum under First Amendment law. As a result, blocking these users from replying to and retweeting Trump tweets violated the First Amendment.

To qualify as a public forum, the government must “intend to make the property generally available to a class of speakers,” Buchwald writes. “The government does not create a public forum by inaction or by permitting limited discourse, but only by intentionally opening a nontraditional forum for public discourse.”

In what seems to us like the weakest part of the decision, Buchwald concludes that the “interactive space” around Trump’s tweets qualifies under this standard. “Anyone with a Twitter account who has not been blocked may participate in the interactive space by replying or retweeting the president’s tweets,” she writes. The Trump administration has advertised Trump’s Twitter account as a way for Trump to communicate directly with the public, she notes.

One way to look at this is that Trump is deliberately creating a public forum each time he writes a new tweet. But it seems at least as likely that Trump has no particular desire to create a public forum—that he considers the public’s ability to post publicly visible replies to his tweets to be an incidental or even unwelcome part of how Twitter functions.

On the other hand, if Trump’s goal were merely to get annoying users to stop bothering him, he could accomplish that goal just as well using the mute button. This button prevents tweets from muted accounts from showing up in Trump’s timeline and notifications, but it doesn’t prevent muted users from replying to and retweeting Trump’s tweets. The fact that Trump chose to block users instead suggests that his goal was to prevent them from communicating with others. And that could be seen as a sign that Trump is trying to shape discourse in the public forum he previously created.

If Buchwald’s ruling is upheld on appeal, it’s likely to create a lot more work for the courts in the future. In last year’s ruling about Facebook blocking, the judge held that public officials could do a certain amount of content moderation, provided that it was done in a content-neutral manner. But in heated political debates, the line between legitimate moderation and illegitimate censorship isn’t always obvious. So expect more lawsuits to establish exactly when and how public officials are allowed to use moderation and anti-harassment tools.

*