Trump’s Recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s Capital Shatters the International Consensus

The Trump administration’s plan to move the US Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem shatters the international consensus and must be viewed against the history of Israel’s ethnic cleansing of the city’s Arab population and Israel’s efforts to conceal its designs on the city. Sovereignty that might be asserted over Jerusalem by Israel was regarded as the death knell of any possibility of reconciliation as the United Nations worked in 1947 and 1948 to fashion a solution for post-Mandate Palestine. A central feature of the UN General Assembly’s partition plan of 29 November 1947 was to keep the status of Jerusalem open until an overall accommodation on Palestine could be achieved. An international administration was to be established to run the city, at least for a temporary period.

In military hostilities against Jordan in 1948, Israel tried to take Jerusalem. The result was a city divided between Israel in the western sector and Jordan in the east. Working against the aim of the partition resolution, Israel began making the sector under its control the administrative centre of its government in the latter months of 1948. At that time, however, Israel was applying for membership of the UN, and these moves cast doubt on whether the new state was a “peace-loving” country, a pre-requisite for membership set out in the UN Charter.

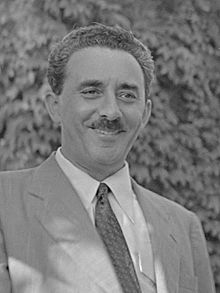

Abba Eban (image on the right) was the architect of Israel’s campaign for UN membership. He convinced its leaders to go slow on activities in Jerusalem in order to get Israel into the international organisation. In March 1949, Israel succeeded in gaining approval from the UN Security Council for its membership application. The application then went for the General Assembly to have the final say.

Open hearings were held, in which Eban was quizzed pointedly about Israel’s intentions regarding Jerusalem. He was asked whether “Israel will do everything in its power to co-operate with the United Nations in order to put into effect the General Assembly resolution of 29 November 1947 on the internationalisation of the City of Jerusalem and the surrounding area.” Eban replied,

“The question of sovereignty over the area has not yet been finally settled and will be settled, perhaps, at the fourth session of the General Assembly. It will not be for the Government of Israel alone to determine that issue of sovereignty. All we can do – and even then only if we are members of the United Nations – will be to propose formally certain solutions of our own.” He added, “We should suggest that the incorporation of the Jewish part of Jerusalem in the State of Israel should receive formal recognition by the General Assembly.”

Eban was also asked “whether, if Israel were admitted to membership in the United Nations, it would agree to co-operate subsequently with the General Assembly in settling the question of Jerusalem,” or “whether, on the contrary, it would invoke Article 2, paragraph 7, of the Charter which deals with the domestic jurisdiction of States?”1 That particular article of the UN Charter reserves matters of domestic jurisdiction to member states. Eban said that it would not be invoked by Israel to claim sovereignty in Jerusalem because, he said, “the territory of Jerusalem… has not the same juridical status as the territory of Israel.”

Those assurances that Israel would not claim Jerusalem proved sufficient to get the UN General Assembly to vote for it to become a member state. That vote was taken in May 1949. Once admitted to membership, Israel no longer felt the need to conceal its aims regarding Jerusalem. In November the same year, Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett (image on the left) addressed the issue of Jerusalem at the UN. He contradicted Eban’s assurances.

“The Jews,” he said, “had regained not merely their stake in Jerusalem, but the link between it and the State of Israel.”

The State of Israel, Sharett insisted, and the City of Jerusalem should constitute an inseparable whole.2

Sharett’s claim was soon the reality on the ground.

“Jewish Jerusalem is an organic and inseparable part of the State of Israel,” declared Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in the Knesset (parliament) on 5 December, 1949. “It is inconceivable that the UN should attempt to sever Jerusalem from the State of Israel or to infringe the sovereignty of Israel over its eternal capital.”3

The Knesset voted in favour of Ben-Gurion’s statement.4 That prompted the UN General Assembly to adopt a resolution re-affirming that Jerusalem must be internationalised.5 Two days later, though, the Knesset voted to make Jerusalem the seat of the Israeli government.6 Ben-Gurion moved his own office demonstratively from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.7

In 1953, Israel’s Foreign Ministry was also moved to Jerusalem, a move denounced by the US government.8 Foreign governments typically place their embassies in proximity to the host government’s foreign ministry, for ease of contact. However, foreign governments which had at that stage diplomatic relations with Israel kept their embassies in Tel Aviv, to avoid any acknowledgment of Israel’s claim to Jerusalem as its capital.9

In June 1967, Israel attacked Egypt, leading Jordan to come to Egypt’s defence, although it was unsuccessful. Israel then moved against Jordan and occupied the eastern sector of Jerusalem along with eastern Palestine on the West Bank of the River Jordan. Once in control of east Jerusalem, the government of Israel decreed that Israeli law would apply there. That measure prompted the UN General Assembly to denounce Israel for asserting sovereignty over the whole city. Abba Eban claimed in the General Assembly that the measure was undertaken for administrative convenience only and was not an assertion of sovereignty. In 1980, however, the Knesset adopted a Basic Law in which it declared “united” Jerusalem to be Israel’s capital. Thus, in the early post-1947 years and again in 1967, Israel, fearing international reaction, had tried to conceal its claim of sovereignty over Jerusalem.

The 1980 Basic Law only reinforced the resolve of foreign states to reject the Israeli claim to Jerusalem. The US, for example, maintained only a consular office in the city, and that office reported not to the US Embassy in Tel Aviv but directly to the State Department in Washington. The generally-held view of the international community has remained that the issue of sovereignty over Jerusalem — both west and east — has yet to be resolved.

Israel’s deception in concealing its claim to Jerusalem was accompanied by actions on the ground to clear Jerusalem of its Arab population. It was able to maintain its hold on the city, starting in 1948, by expelling the indigenous Arabs. On 31 December, 1947, for example, the Zionist leadership set in motion a policy for the ethnic cleansing of the city, a policy it implemented in the following months through bombings and assaults on Arab civilians. On 7 February, 1948, Ben-Gurion told colleagues in his Mapai Party, “Since Jerusalem’s destruction in the days of the Romans, it hasn’t been so Jewish as it is now.” In “many Arab districts” in Jerusalem, he pointed out, “one sees not one Arab. I do not assume that this will change.”10

Since occupying the eastern sector of the city in 1967, Israel has engaged in protracted ethnic cleansing. The state regards Arab residents of the eastern sector as only holding residency rights that may be forfeited by extended stays abroad. This policy is in clear violation of the international rules regarding belligerent occupation, which require respect for the status rights of the occupied population.

In this fashion, Israel has accomplished by administrative regulation since 1967 what it accomplished by force of arms in 1948 in the city of Jerusalem, namely, a substantial reduction of the Arab population. Under international law, a situation brought about by unlawful means is not supposed to be recognised by other states.

The Trump administration’s acceptance of Israel’s claim to Jerusalem, therefore, means that Washington is condoning the state’s ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian Arab population. This is a clear violation of the consistent international consensus that the status of Jerusalem must be resolved in a peaceful way.

*

Notes

1 UN General Assembly, 3rd session, Part II, Ad Hoc Political Committee, Summary Records of Meetings 6 April – 10 May 1949, 47th meeting, May 6, 1949, at 273 and 278, UN Document A/AC.24/SR.47.

2 UN General Assembly, 4th session, Ad Hoc Political Committee, Summary Records of Meetings 27 September – 7 December, 1949, 44th meeting, November 25, 1949, at 261, UN Document A/AC.31/SR.44.

3 Statement by the Prime Minister concerning Jerusalem and the Holy Places, December 5, 1949, Divrei Haknesset (Records of Knesset Proceedings), vol. 4 (2nd session), at 81-82, translated in Lapidoth and Hirsch, The Jerusalem Question and Its Resolution: Selected documents (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994), at 81-82.

4 Israel defies UN over rule of Jerusalem, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 6, 1949, at 7. Premier holds decision void, New York Times, December 6, 1949, at 23.

5 UN General Assembly, Resolution 303, December 9, 1949.

6 Michael Brecher, Decisions in Israel’s Foreign Policy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), at 12, 28-29.

7 Israel defies U. in Jerusalem move, Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1949, at 25.

8 US Position on Transfer of Israeli Foreign Office: Press Conference Remarks by Secretary Dulles, July 28, 1953, Department of State Bulletin, vol. 29, at 177 (August 10, 1953).

9 Walter Eytan, The First Ten Years: A Diplomatic History of Israel (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1958),at 78.

10 Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), at 69-70.

Featured image is from Samuel Corum – Anadolu Agency.