Trump’s North Korean Obsession

Since Donald Trump‘s victory, tensions in the Korean Peninsula have reached almost unprecedented levels. This aggressive approach from the new administration has accentuated tensions with Pyongyang, leaving one to wonder whether another US war is in the making.

During the election campaign, Trump often took ambiguous and, in some respects, isolationist positions concerning hotspots around the world. The exception to this rule has often been North Korea. Business Insider cites the current US president speaking in January of 2016 about the DPRK with the following words about its nuclear program:

“We got to close it down, because he’s getting too close to doing something. Right now, he’s probably got the weapons, but he does not have the transportation system. Once he has the transportation system, he’s sick enough to use it. So we better get Involved.”

As soon as he became president, the words became even more threatening, clear and explicit, with this tweet becoming famous:

“North Korea just stated that it is in the final stages of developing a nuclear weapon capable of reaching parts of the US. It won’t happen!”

A few weeks later, words were turned into action: the United States and its allies (South Korea and Japan) carried out two enormous exercises between March and April 2017. The first, focusing on land and sea operations and named Foal Eagle, involved tens of thousands of US and South Korean soldiers and naval warships. A few weeks later the Max Thunder 17 exercise kicked in, with dozens of aircraft involved. In both exercises the goal is to focus on the DPRK, with simulations of an attack by the United States and its allies by land, sea and air.

From Pyongyang’s point of view, the deterioration of relations with the US, South Korea and Japan has risen beyond any tolerable limit with a vicious cycle of tensions on the Korean Peninsula, since Trump’s assumption of the presidency. The United States, the world’s premier military power, continually threatens to bomb and invade the DPRK with thousands of soldiers, or threatens to kill Kim Jong-un. As if this situation were not tense enough, the ongoing exercises by the US and her allies suggest a realistic possibility of invasion rather than a simple exercise (usually wars begin simultaneously with great maneuvers, since in such exercises forces are already deployed, operational, and ready to fight). Finally, to top off the madness coming from Washington, Trump repeatedly broached a change in the historical strategic balance reflected by MAD (mutually assured destruction), floating the idea of arming South Korea and even Japan with nuclear weapons.

Nuclear deterrence for peace

In light of all these historical provocations and threats, Kim Jong-un has in recent years had to accelerate his atomic program and demonstrate the consistency of DPRK’s nuclear capability and convincingly deter opponents. In order to asses the capacity of North Korea to hit the US with a WMD, one has to take into consideration two main factors: the ability to create a nuclear warhead, and the method of delivery.

The first, concerning the ability to detonate a domestically manufactured nuclear bomb, is already a fact acknowledged by the international community and demonstrated with five nuclear tests. The second question focuses on the means used to deliver the nuclear weapon. With the first question already a known fact (the DPRK has up to 30 nukes), this only leaves the assessment of missile range and reliability, which will be discussed later. For now, it is important to focus on the motives that may have driven the DPRK to develop an nuclear program. During American exercises, North Korean reservists from the countryside were often summoned from the countryside when they were most needed for harvesting and planting seasons, creating significant strains in the agricultural area so vital to the country’s economy.

Thanks to the nuclear deterrent, the amount of people recalled has been considerably reduced due to the reduction in the likelihood of an American attack on the peninsula.

Obviously nuclear deterrence plays a key part in North Korea’s defensive posture, but we can further consider the lesser known determinants of this strategic choice. First of all we can consider the reduction in military spending on conventional means of war by the possession of a nuclear deterrent. Pyongyang’s ability to almost market its nuclear deterrence with nuclear and missile tests is certainly more cost effective than building thousands of multiple-launch rocket systems (MLRS) and mortar rounds. This does not mean that in a military assessment of conflict, such equipment does not tip the balance of power; we will see that they do exactly this.

The DPRK’s deterrence policy is a much more complex matter than just its nuclear component. The common idea is that with a nuclear bomb Pyongyang is safe. That is true on the basis of the theory of MAD. But with missile defense systems in play, this could change the equation, or maybe not. What really makes the DPRK safe is conventional weapons and geography.

China Cannot Help Disarm Pyongyang

Regarding the considerations made by Pyongyang on nuclear disarmament, it is interesting to note that the North Korean leadership has often referred to the promises made by the west to Gaddafi regarding Libya’s nuclear disarmament, and the consequences of this choice seen in the subsequent attack on Libya and the killing of Gaddafi. Kim Jong-un has repeatedly made it clear that trusting Washington and its allies is simply impossible given these historical precedents.

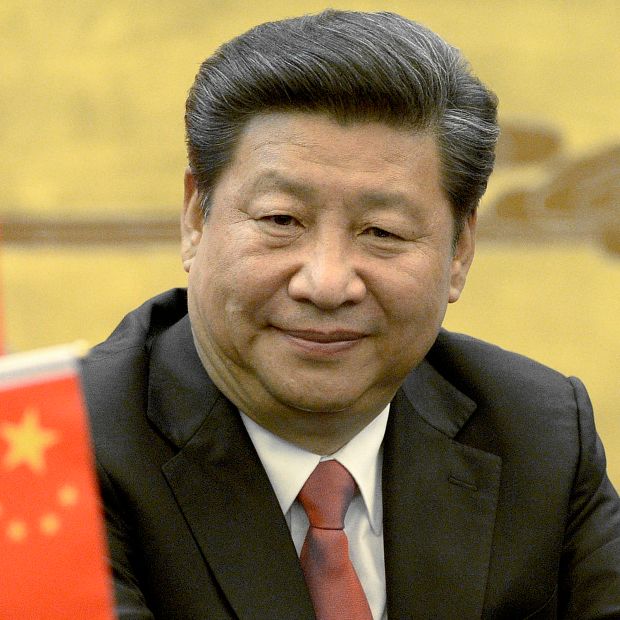

Another important factor when talking about the Korean Peninsula is the common notion of Beijing’s influence on Pyongyang. Trump has on several occasions made it clear that China is the only actor capable of putting sufficient pressure on Kim in order to force him to disarm or stop missile tests. But this is a political position that leaves many questions and doubts and is based entirely on the notion that Beijing is assisting Pyongyang economically and so has the necessary leverage. This, for Washington, means that if Xi wanted to shut down the Korean economy and oblige DPRK’s leadership to dialogue, he could do so.

Another important factor when talking about the Korean Peninsula is the common notion of Beijing’s influence on Pyongyang. Trump has on several occasions made it clear that China is the only actor capable of putting sufficient pressure on Kim in order to force him to disarm or stop missile tests. But this is a political position that leaves many questions and doubts and is based entirely on the notion that Beijing is assisting Pyongyang economically and so has the necessary leverage. This, for Washington, means that if Xi wanted to shut down the Korean economy and oblige DPRK’s leadership to dialogue, he could do so.

Reality, however, shows us that Beijing has little influence on the Korean leader, and a deeper analysis shows how the DPRK is forced to trade and talk to China more out of practical need than any desire to do so. Further evidence shows how the relationship between China and the DPRK is at the very least complicated.

Realistically, it is difficult to ignore the contribution of the former Soviet Union, and then Russia, to the DPRK’s conventional and possibly nuclear development. The last parade of arms on April 15, 2017 saw the DPRK parade hardware very similar to that of the Russian military, especially the large Topol-M. Of course Beijing has a longstanding interest in the DPRK and with the state’s survival. The DPRK ensures that there are no hostile forces on China’s southern border. Beijing has learned the lessons from the end of the Cold War, where, following various pledges to Russia not to extend NATO into Eastern Europe, NATO subsequently expanded right up to Russia’s borders, directly threatening the Russian Federation.

Beijing supports the DPRK to avoid a unified Korea under US guidance that would pose a real threat to the Chinese state. In this context, Beijing faces diplomatic consequences at an international level, facing criticism and threats of armed intervention in the DPRK if Beijing does not do something to stop the North Korean leader.

It is a very complicated situation for Beijing, which finds itself between a rock and a hard place, having little real ability to influence Kim’s choices. From the point of view of the DPRK, the best outcome would be an agreement with the United States and Japan to loosen sanctions and embargoes. The problem is what these nations ask for in return is complete disarmament. For the reasons cited above, this solution is virtually impossible because of the complete lack of trust by all actors.

From words to nothing

At this point it is good to go to the heart of the matter and to analyze the most interesting aspects. First of all, Trump’s actions in Syria, as well as the use of a MOAB in Afghanistan, sought to put pressure on Kim Jong-un to make him come to the negotiating table. This obviously did not work, it being utterly unrealistic to commence negotiating with Pyongyang on the basis of threats of war. The DPRK has been besieged for over 50 years, and 50 cruise missiles, or a ten-ton bomb, will hardly do anything to change their position or scare them. The DPRK is neither Syria nor Afghanistan.

The subtle line between deception and perception in the Korean nuclear affair is certainly of great interest. We should begin by saying what we know. The DPRK as a country is a tightly state monitored system from many point of view, in terms of information, the internet, computer systems. Any information we read in the mainstream media on the DPRK should therefore be treated as propaganda. Two aspects are to be considered, namely what the DPRK wants western military planners to believe, and what the western press wants public opinion to know and believe about the DPRK. Let us take a practical and vital example in this discussion by looking at the range of the missiles mentioned in previous paragraphs.

We start with a basic premise stated by Washington, namely that the United States will prevent the DPRK from developing a missile (ICBM) capable of reaching American territory with a nuclear warhead. The DPRK is in response developing an ICBM that can reach US soil in order to gain the ultimate deterrent weapon and so ensure its safety. In reality, we cannot know what the DPRK’s capabilities are until they test them. And with regard to that, the US administration has limited interest in publicizing possibile DPRK achievements and hinting that Pyongyang could hit the US with a nuclear warhead. That would then arise domestic pressures exerted throughout the press, politics, think-tanks, the military, the intelligence community, and external actors (Japan and Korea) to attack North Korea.

Likewise, the DPRK has no interest in eventually testing an ICBM already knowing well that the United States would have its back against a wall, leaving it with no choice but to attack.

Federico Pieraccini is an independent freelance writer specialized in international affairs, conflicts, politics and strategies.