Trump’s Foreign Policy After 100 Days: Tweeting with Bombs?

As US President Donald Trump prepares to mark 100 days in office, the administration’s foreign policy approach has become a painful disappointment to anyone with mildly optimistic expectations Washington would take a more realist approach to its role in the world.

In no time at all, Trump has strayed from the ‘America First’ rhetoric on the campaign trail and reversed course in a remarkable way. His decision to launch cruise missile strikes against Syria’s government on painfully a pretense, humiliatingly revealed to China’s leader over a piece of chocolate cake, is the picture of volatility.

Establishment pundits who had bogusly derided Trump as a Russian stooge christened him “presidential.” Buoyed by this bipartisan support for militarism, the Pentagon dropped the largest non-nuclear bomb in a distant corner of Afghanistan, likely without Trump’s direct approval as part of his policy of giving the military a freer hand to act.

Far from “isolationism” or a realist repositioning of American foreign policy, Trump represents the continuity of endless warfare and US militarism’s pursuit of global hegemony, different in perhaps only it’s cruder, more impulsive presentation and televised set pieces with higher explosive yields.

A pragmatic US-Russia détente remains as elusive as ever, for obvious reasons. It is extremely disconcerting that Trump, whose approval ratings have hit historic lows, was so enthusiastically supported by the US political and media establishment for his display of military muscle.

Trump’s vivacious and approval-seeking personality, his shallow understanding of strategic affairs and his proneness to react to media coverage make him more prone than ever to the temptation of launching one-off cruise missile strikes in a “Wag the Dog” style publicity coup. Call it “tweeting with bombs.”

Nowhere is this propensity for impulsive militarism more dangerous than the Korean peninsula, where a provocation or miscalculation can quickly spiral out of control with unbearable and unthinkable humanitarian consequences. Trump himself hinted at unilaterally bombing North Korea as if the spectacles of Syria and Afghanistan hadn’t got the message across.

It’s crucial to understand that any US use of force to degrade North Korea’s weapons program would start a major war in Northeast Asia, both the world’s most densely populated region and a main driver of global economic growth, with some of the world’s busiest airports and container ports.

On a recent visit to South Korea, US Vice President Mike Pence declared the Obama-era policy of ‘strategic patience’ had come to an end, warning Pyongyang against conducting further nuclear or long-range missile tests to avoid triggering an unspecified US response.

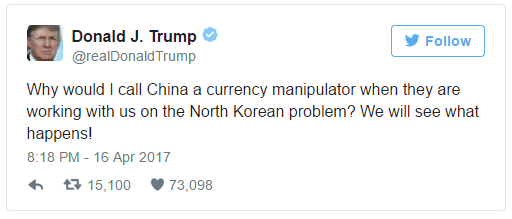

Aside from the familiar adage of “all options on the table,” the Trump administration’s policy toward Pyongyang continues to lack a precise definition. The White House has recently completed a review of North Korea policy and settled on what it calls a policy of ”maximum pressure and engagement.”

This seems to mean the US will enforce tougher sanctions and pressure in other ways while leaving the door open for some form of negotiation. Trump, like the veritable leader of a global empire, recently summoned ambassadors of countries on the UN Security Council for a working lunch to call for tougher sanctions on North Korea.

He has also taken the extraordinary step of inviting the entire US Senate to the White House to be briefed on the administration’s North Korea policy. The outcome of a maximum pressure and engagement policy is certain not to achieve US strategic objectives unless accompanied by a level of flexibility previous administrations have been unwilling to show.

Firstly, Pyongyang has very limited exposure to global markets, and it cannot be expected to respond to economic sanctions in the same way as Iran, an energy exporter and key regional power, which agreed to a deal with the Obama administration for economic and financial sanctions relief.

North Korea is already the world’s most sanctioned country, and it has still achieved a modest level of economic growth in recent years. Pyongyang’s policy makers treat sanctions as a fact of life, and they’ve given every signal that they are prepared to stay the course.

Secondly, the chance of negotiating a peaceful end to North Korea’s weapons program is exceedingly unlikely, and for very logical reasons. Pyongyang has learned from the mistakes of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi, and will not give up its strategic nuclear deterrent, which serves both a critical security function and a symbolic function, one of immense national pride.

The Obama administration would only engage in dialogue with Pyongyang on the precondition that it agreed to commit to denuclearization. Unsurprisingly, this approach failed, and North Korea made strides in developing its nuclear capability. If the biggest carrot of Trump’s “engagement” policy involves the characteristically arrogant capitulation-for-dialogue approach, then no deal.

Pyongyang has signaled on numerous occasions a willingness to freeze nuclear development and missile tests in exchange for a peace treaty to formally end the 1950s-era Korean War (which ended in an armistice) and a moratorium on US and South Korea joint military exercises, which it views as a dress rehearsal for invasion.

This is the only soft landing in sight, and the outcome would far better serve the region’s security and development interests. Consequently, South Koreans are widely expected to elect opposition leader Moon Jae-in as president in polls scheduled for May. Moon favors engagement and détente with Pyongyang, a dramatic reversal of the policies taken by the outgoing conservative administration in Seoul.

He is also opposed to the earlier-than-expected deployment of the THAAD anti-missile defense system to the country and aims to hasten the transfer of wartime operational control of South Korea’s armed forces to Seoul, rather than the US military. For these reasons, he could find himself at loggerheads with the Trump administration.

Ultimately, Donald Trump as a politician narcissistically seeks attention and a dramatic victory to hold up as an example of how fantastic he is. Whether this is achieved through peace and deal-making or war and coercion is secondary to the man. He is not a student of history or a strategic thinker. He has no values or ideology apart from his ratings and his brand.

From the vantage point of his first 100 days in office, Trump appears to be channeling the foreign policy strategies of Ronald Reagan: a massive military build-up accompanied by threatening displays of strength as a means of gaining leverage over adversarial powers.

In any case, it didn’t take long for Trump to fold on the populist rhetoric and realist foreign policy of his campaign. The bitter irony is that the United States now finds itself back on a more-or-less Clintonian foreign policy trajectory. As Americans say, the only sure things in life are death and taxes… and the continuity of a militaristic US foreign policy.

Nile Bowie is an independent writer and current affairs commentator based in Singapore. Originally from New York City, he has lived in the Asia-Pacific region for nearly a decade and was previously a columnist with the Malaysian Reserve newspaper, in addition to working actively in non-governmental organisations and creative industries. He can be reached at [email protected].