Trump’s Cowardly War on Immigrant Children

Like clockwork, every Sunday night I talk to my parents (by way of explanation, I live in New York, they reside in Rancho Mirage, California—a distance that makes in-person discussions somewhat difficult to manage). After catching up on family news, inevitably our conversation devolves into politics. I had (infamously, in my mom’s view) predicted Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election shortly after the Democratic National Convention in July of that year, citing Hillary Clinton’s shortcomings as a candidate more than Trump’s positives. My mom, a Clinton supporter, was aghast that I could side with such a fundamentally flawed character as Trump. In the time Trump has held office, Mom has unfailingly sought to remind me of the president’s obvious (in her mind) failings as a leader and a human being. Our last conversation was pretty much along the same lines—wishing my dad a happy Father’s Day, talking about my niece’s graduation from high school and her future college prospects, the U.S. Open, and—inevitably—Trump.

Normally, I laugh my way through this part of the conversation. This time, however, we were discussing the ongoing policy of separating children from the parents of immigrants who illegally cross into U.S. territory. While I am far more liberal on immigration policy than President Trump, I respect the fact that he was elected as the chief executive and as such is responsible for setting policy. I was perturbed at Congress for failing to jump at the president’s offer to clear the way for more than a million immigrants to legalize their status in exchange for providing him with the funds needed to build a border wall, which was the centerpiece of his presidential campaign. However, like my mom, I was (and am) aghast at what is happening along the U.S.-Mexico border today—between mid-April and the end of May of this year, 1,995 children have been physically separated from their parents at the border. Hundreds more have been taken away since then.

Domestic politics is not my comfort zone—I’ll take weapons of mass destruction and arms control issues over health care and tax policy any day of the week. After I articulated my disdain for the current policy, however, my mom challenged me.

“You write about all these other issues,” she said. “Why don’t you write about this one?”

I threw out the standard excuse—not my area of expertise. Mom did not relent, pressing me harder. I finally came up with the weakest answer I could possibly give—it wouldn’t make any difference, and worse, it could lead to a backlash that might hurt my chances at getting picked up by conservative publishers in the age of Trump. The bottom line, I said, mattered. Mom relented.

After we hung up I reflected on my answer, and found it wanting. I tuned in to the Sunday news shows, listening to commentators from both sides of the political aisle address the issue. I looked at the imagery of children sitting in cages, put there by sworn American law enforcement officers. And I listened to the sounds of children crying as they were taken away from their parents, begging the officers involved to let them stay. I’m a rule-of-law kind of person, and I believe that all nations—not just the United States—have a sovereign duty and responsibility to their citizens when it comes to securing their borders. In my view, America’s immigration policy—which directly impacts the issue of border security—is fundamentally broken, and I support the efforts of those, Democrat and Republican alike, who are working to resolve this issue.

Children in immigration detention facilities are required to recite the Pledge of Allegiance each morning, according to the Washington Post. (Photo: U.S. Customs and Border Patrol)

I’m also a parent, and someone who supports the right of all human beings to live a life free of oppression. In my opinion, what America was—and is—doing to the children of immigrants detained at the border represented the most vile, base form of oppression, if for no other reason than it targets the most innocent and defenseless for the sole purpose of making a political point (i.e., funding for Trump’s vaunted border wall.) Moreover, it awoke within me memories of an experience from my past involving incarcerated children, one in which I had been called upon to weigh the horrors of the images and sounds of their suffering with what I deemed to be a “larger purpose” of stopping a war. My mom’s insistence that I write something that addressed the human tragedy transpiring on America’s border with Mexico prompted me to reflect on that decision, and the larger question of whether the suffering of children can be condoned under any circumstance.

In March 2002, the on-line magazine Salon ran an interview with me conducted by Asla Aydintasbas. Midway through the interview, Aydintasbas asked about defining Iraq beyond simply Saddam Hussein, its former ruler. In my answer, I spoke about what I had seen during my seven years as a United Nations inspector—the institutions that made Iraq and the people who ran them. The point I tried to make was that Iraq was more than just one man, both in terms of the good, the bad, and the ugly. In underscoring the “ugly” aspect of what I had witnessed, I told Aydintasbas that

“I’ve been to the children’s prison at Amn al-Amm [the Directorate for General Security headquarters in downtown Baghdad]. It was horrific; these are kids in jail under horrific conditions, sweltering because of the political crimes of their parents. Dad speaks out about Saddam, Mom goes to the women’s prison, the kids go to the children’s prison. And do you know what they do to those kids? I don’t even want to get to that.”

To me, it was a throwaway moment in one of a long series of interviews I was giving at the time to draw attention to what I believed to be the real threat of an American invasion of Iraq. Aydintasbas pushed me several times to consider the horrific nature of Saddam’s rule as justification for regime change. I wouldn’t buy it:

“I just cannot accept the argument that we have to intervene to remove Saddam Hussein on moral grounds.”

I pointed out that an estimated 1.5 million Iraqis had died due to economic sanctions imposed on Iraq linked to its disarmament obligation.

“We have killed almost six times as many Iraqis trying to eliminate weapons of mass destruction programs than weapons of mass destruction have killed in the entire 20th century—that’s a moral issue to me.”

The issue at hand was an incident that occurred during an inspection I led in Iraq on Jan. 11, 1998, as a chief weapons inspector for the United Nations Special Commission, or UNSCOM. We were investigating a sensitive piece of U.S.-sourced intelligence which claimed Iraq had conducted experiments using biological agents on live human subjects in the summer of 1995. The information was dated but contained enough specifics to investigate—the prisoners were taken from specific prisons by agents of the Amn al-Amm to remote locations in the desert where the experiments were conducted. UNSCOM was under a lot of pressure from the United States to come up with a smoking gun that proved Iraq was in violation of its obligation to disarm, and the American intelligence was infused with enough troubling data to make it appear credible and give inspectors something to search for during an inspection. After consulting with the White House, UNSCOM ordered me to carry out an inspection. I organized the inspection team into two elements—one would inspect the notorious Abu Ghraib prison, the other would visit the Amn al-Amm.

Given the sensitivity of entering the Amn al-Amm, which served as the headquarters of Saddam’s secret police, I put myself in charge of the group inspecting that site. Our presence at the main gate created near panic on the part of the Iraqis—they had not expected us to attempt such a brazen inspection of one of their most sensitive facilities. Per existing inspection protocols, I was eventually allowed to enter along with a team of three inspectors. Our goal was the office of the director, where I would lead a detailed and focused search for any documents that might be related to the human experiments alleged to have been conducted in 1995. I split the team in half to facilitate our survey of the site. My element proceeded to inspect parking garages, residential complexes for the officers and families of the Amn al-Amm, armories and, in the basement of an office building, what could only be described as a children’s prison.

The inspector accompanying me had called me over to a series of ground-level windows looking in on the basement of the structure. Through the barred windows I could see dozens of children, boys and girls of varying ages. The stench was awful—it was obvious the rooms they were crammed into had open latrines and no access to water. When the children saw our faces, a cry went up inside the room, with the ones closest to the windows making gestures at their mouths as if they were hungry and wanted to eat. The Iraqi official accompanying me hurried up to my side. “This has nothing to do with your mandate, Mr. Ritter. Move on.”

My teammate and I headed back to our parked vehicle, but instead of getting inside and driving off, I opened the back of the white U.N. Nissan Patrol SUV and grabbed as many two-liter water bottles and Meals Ready to Eat (MRE) packets from our contingency supply as I could carry, instructing my teammate to do the same. I pushed past the Iraqi official, and made my way back to the windows, where we handed the water and food into the children inside. Within seconds there were armed Amn al-Amm agents standing next to us, pushing themselves between us and the children in the basement, whose arms extended through the window. “That’s enough, Mr. Ritter,” the Iraqi official said. “It’s time to go.”

The look in his eyes, and in those of the armed agents, left little doubt he was deadly serious. I threw the remaining bottles and packets at the window, hoping the kids inside would be able to catch them, but watched in frustration as the Amn al-Amm agents kicked them away. As we left, the agents made their way into the building, where there was no doubt in my mind that they would confiscate the water and food we had handed to the kids. There was nothing either my teammate or I could do except hope the kids would drink and eat as much as they could in the little time they had.

We eventually found the office we were searching for and, given the sensitivity of the location, agreed to meet with the senior Iraqi leadership, including the deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz, later that evening to discuss how best to proceed with a document search. As soon as we exited the facility, the Iraqis ceased all cooperation with the team, labeling me a CIA spy and agent provocateur. UNSCOM found itself in a fight for its survival, and I was at the center of the storm. My every move was being tracked by foreign governments and the press, none of whom were looking out for either my or UNSCOM’s best interests. I was muzzled by my leadership, prohibited from saying anything to anybody while negotiations took place to get inspections back on track. Moreover, even if I had been allowed to speak, the children’s prison would have been the last thing I would have brought up. I had been accused by Iraq of being a spy. My only defense against such a charge was to adhere to the four corners of my mandate as an inspector and exclusively focus on the mandate of disarmament we had been given by the U.N. Security Council.

In August of 1998 I resigned from UNSCOM, protesting the failure of the U.S. to support the work of the inspectors. In September 1998 I testified before Congress about weapons inspections in Iraq, and in early 1999 I wrote a book, “Endgame,” which focused on the Iraq crisis from the perspective of its disarmament obligation. I made scores of public appearances, speaking on the topic of Iraq and weapons of mass destruction, and wrote numerous articles and opinion pieces on the subject. I never once raised the topic of the Amn al-Amm children’s prison, as it simply was outside the scope of my primary focus, which was at the time trying to prevent a war with Iraq being fought over the false pretense of a retained Iraqi weapons of mass destruction capability. In fact, my interview with Aydintasbas was the first time I had publicly discussed the incident of the children’s prison.

In September 2002, to head off what I deemed to be a rush to war by the George W. Bush administration, I returned to Iraq, where I addressed the Iraqi Parliament and met with senior Iraqi government officials in an effort to convince them to allow U.N. weapons inspectors to return to work and, in doing so, undercut the case America was making for an invasion. In the aftermath of this visit (which proved successful—shortly after I departed Iraq, Saddam announced that he would allow U.N. weapons inspections to resume), I was interviewed by several media outlets about what I was trying to accomplish. One of these interviews, conducted by Massimo Calabresi, appeared in Time magazine. In it, Calabresi asked me to describe what I had seen at the children’s prison in Iraq.

“The prison in question is at the General Security Services headquarters, which was inspected by my team in January 1998,” I replied. “It appeared to be a prison for children—toddlers up to pre-adolescents—whose only crime was to be the offspring of those who have spoken out politically against the regime of Saddam Hussein. It was a horrific scene.”

I then reverted to inspector mode, trying to get the discussion back on topic, which for me was the issue of Iraq’s disarmament obligation.

“Actually,” I said, “I’m not going to describe what I saw there because what I saw was so horrible that it can be used by those who would want to promote war with Iraq, and right now I’m waging peace.”

As I had explained early in the interview, “waging peace” was about facilitating “a debate here in the United States on America’s policy toward Iraq, a debate that’s been sadly lacking. We’re facing a critical moment in American history and I believe this is something that has to be more thoroughly looked at.” I argued that

“no one has backed up any allegations that Iraq has reconstituted WMD capability with anything that remotely resembles substantive fact.”

Moreover, as I pointed out to Calabresi, the U.S. had “tremendous capabilities to detect any effort by Iraq to obtain prohibited capability. The fact that no one has shown that he has acquired that capability doesn’t necessarily translate into incompetence on the part of the intelligence community. It may mean that he hasn’t done anything.” The Bush administration was arguing that Iraq had a WMD capability; I was challenging that assertion. Children’s prison’s, in my opinion, weren’t part of that debate.

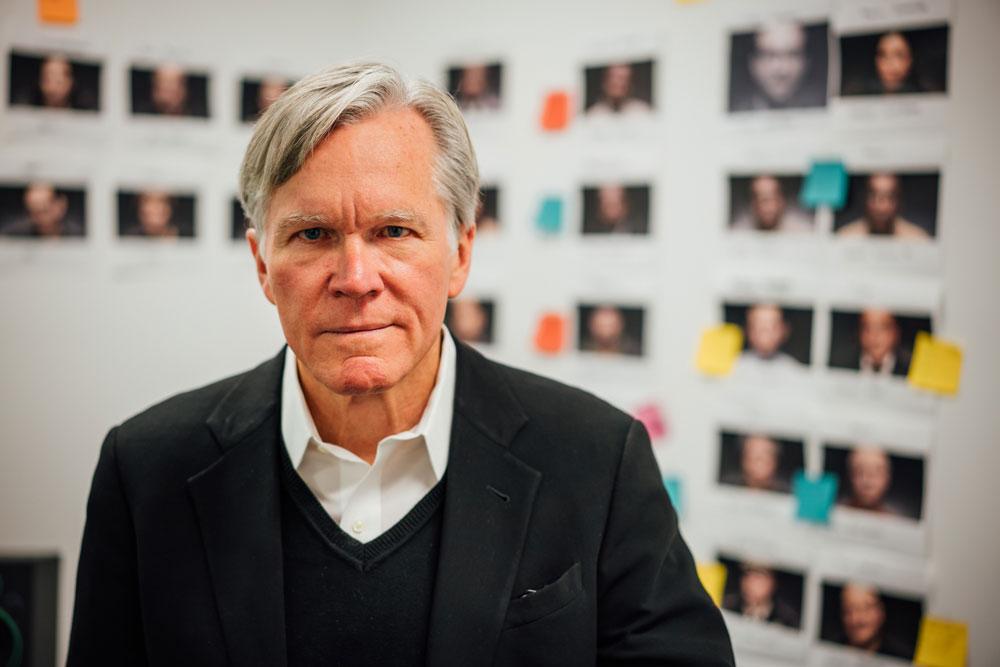

Some people took umbrage at the notion. This included Bill Keller (image on the left), the former managing editor of The New York Times, who, on December 14, 2002, while serving as a senior writer and op-ed columnist for the Gray Lady, wrote an editorial titled “The Selective Conscience,” in which he called me out by name for my stance. He articulated it as representing the “apotheosis” of the “high-minded quandary” confronting human rights proponents when dealing with the issue of a possible war with Iraq.

To his credit, Keller fairly articulated my position:

“Officially, formally, Saddam’s depravity is not relevant to the question of whether America will lead a military effort to oust him. The question of invasion—officially, formally—is all about ridding Iraq of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons and the means to deliver them.”

However, according to Keller,

“the barbarity of the regime is subtext to everything,” noting that “Saddam’s cruelties also touch a little on two central questions about any exercise against Iraq: What’s the evidence that Saddam is a real threat? (Any leader who encourages the torture of children as a mechanism of control is probably never going to become a good neighbor.) How will Iraqis react to an invasion? (Many of them with an outpouring of relief, wouldn’t you think?)”

In the end Keller took a position on Iraq that supported the notion that the issue of weapons of mass destruction trumped the issue of human rights when it came to a decision on whether to go to war.

“The view I’ve expressed in this space,” he wrote,“is that Saddam’s appetite for a nuclear weapon makes him a grave danger, that containment is ultimately a sucker’s game, and that Mr. Bush is right to prepare for war—purposefully but patiently, hoping it will be unnecessary, and aiming to act as part of an aggrieved world rather than a posse of one. To my mind the sadistic practices of the Iraqi police state, and the more genocidal impulses—now successfully held in check by American and British air patrols—may be ample cause to indict Saddam as a war criminal, but they are not in themselves enough to launch an invasion.”

While inspectors did, in fact, return to Iraq, their work was not enough to forestall President Bush’s desire for war—in March 2003 a U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq and removed Saddam Hussein from power. America’s subsequent 15-year experiment in trying to fashion a stable replacement for Saddam’s regime has shown Keller’s morality-derived analysis to have been wrong—in terms of containing both Iran and the forces of Islamic fundamentalism, Saddam’s regime was not only not a threat, but a force of stability that no post-invasion Iraqi government has been able to replicate. Moreover, the incessant anti-American fighting that has shaken Iraq virtually nonstop since 2003 makes a mockery of Keller’s fanciful “outpouring of relief” the American invasion was supposed to presage.

Having been proved right by events, however, doesn’t resolve the “high-minded quandary” raised by Keller regarding troubling human rights issues such as the existence of the children’s prison in Baghdad, and my decision to suppress that horrific reality in favor of what I deemed a higher purpose—preventing an unnecessary war. On April 8, 2003, U.S. Marines moved into Baghdad and liberated a prison containing 100 to 150 children. I was unable to ascertain from the news article reporting this event whether the prison liberated was the one I had seen, or another—the children were said to have been imprisoned for the crime of refusing to join a pro-Saddam children’s militia, making their offense the kind of political “crime” the Amn al-Amm would be responsible for policing, so it’s possible it was.

The Marines’ action set off a firestorm among the chattering class that populates the comments section of web-based publications. Accuracy in Media (AIM) got the ball rolling, reporting on the liberation of a children’s prison on April 24, 2003, along with commentary that noted “the existence of children’s prisons in Iraq was reported last September by Scott Ritter, former U.N. weapons inspector.” Although factually incorrect (I had first mentioned the children’s prison in my March 2002 interview with Salon), the AIM article went on to speculate that “the liberal media” was following my lead when it came to its failure to widely report on the existence of the children’s prison. In the comments section, a reader posted what appeared to be an original poem commemorating the action of the Marines, commemorating the moment when the Marines “opened wide those prison gates and cast aside that tyrant’s hate.”

The AIM article was picked up by numerous conservative websites, including a Baptist-affiliated online community, Baptist Board, where one commenter noted that the story of the Marines liberating the children’s prison was “not widely reported by the media,” adding that “this alone would be enough for me to want to wage war on Iraq. Forget all the other reasons. A man who would do this had to be deposed.” This was followed by, “Scott Ritter has known about the prison since ’98 and kept it quiet. I wonder how many children were incarcerated, tortured or killed because Ritter decided not to tell the world.”

I take umbrage at the notion that I somehow opted out of telling the world about the Amn al-Amm children’s prison—the only reason Bill Keller, Time, AIM and the others could comment of the prison’s existence is because I opted to reveal what I saw during my interview with Salon. The notion that my somehow not highlighting the children’s prison prior to this interview led to additional Iraqi children being incarcerated, tortured or killed is on its face absurd. Given the context of the Iraq discussion at the time, any deviation away from my area of expertise would have detracted, not added, to the debate. I know this from personal experience—whenever I tried to shift the debate to include the issue of economic sanctions and the resultant suffering of the Iraqi people (including the deaths of some 500,000 children then-U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright infamously dismissed as worth the price when it came to containing Saddam Hussein), I was unceremoniously reminded to stay in my lane.

What does resonate with me from this experience, however, is the legitimacy of outrage that existed regarding the existence of the children’s prison, and the callousness of a world, including myself, willing to turn a blind eye to such depravity in the cause of an erstwhile “greater good.” Today a variation of this argument is being used by the Trump administration, seeking as it does to justify the policy of separating children from parents at the border as a necessary evil in service of the greater good that comes from a strong immigration policy and strict border controls. I’m sure Saddam Hussein and his henchmen had similarly constructed arguments as to why they needed to separate children from their parents as well—national security can be used to conceal many sins.

There is a risk in conflating the Trump policy of child separation with whatever policies the Saddam regime used to justify their children’s prisons; most Americans will agree that there is simply no moral equivalency between the United States and Saddam’s Iraq. I, too, share this believe, which is why I raise the issue to begin with—if the U.S. is morally superior to Saddam’s Iraq, then why engage in a policy of forcibly removing children from their parents and imprisoning these children under conditions child psychologists and legal experts have deemed amount to child abuse that are akin to the past practices of that regime?

Of particular concern is the tendency on the part of many conservatives to defend this practice, including Robert Jeffress, a pastor of the First Dallas Baptist Church, who noted, “Any American who commits a crime is going to be separated from his or her child. You don’t send children to jail with their parents in America, so I’m not sure why the only criminals who would get a pass on that policy would be illegal immigrants.” The “crime” Jeffress alludes to is the act of illegal entry into the United States, which last month the Trump administration announced would be charged as a misdemeanor offense requiring the arrest of the perpetrators and the forcible separation of any accompanying children. “If you are smuggling a child,” Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared when announcing the policy, “then we will prosecute you and that child will be separated from you as required by law.” The problem is, there is no law that requires children to be separated from their parents—this is an invention of the Trump administration.

In the end, the forced imprisonment of children by the United States is not about national security, or any other “higher cause.” It is a purely political move designed to compel Congress to do President Trump’s bidding on the issue of border security. That this cynical mindset has led to the forcible separation and cruel imprisonment of children by the government of the United States is an affront to all Americans. These children are not “child actors”, as Anne Coulter has so callously suggested, any more so than the wretched kids locked up in the Amn al-Amm prison were. What is transpiring on the U.S.-Mexico border today is a testament to the soul of our nation, and how low we have collectively sunk in the name of partisan politics.

I’ll do my part to amend for these shortcomings—Mom was right, I did need to write about this issue. There is no ignoring evil when you see it, especially when that evil is being perpetrated by those who act in your name. But until a judge deems what is happening along the border to in fact constitute child abuse chargeable under the law, and properly mandated law enforcement officials move to cease this practice and arrest those responsible for perpetrating this abuse, or Congress acts and rewrites the laws in question and defunds Trump’s criminal border security enterprise, then my words will have little or no impact.

Unlike what happened in Iraq, there is no Marine invasion force coming to liberate these children from America’s prisons—that can only happen when the people who elected Donald Trump turn on him, something polls suggest has not yet happened. The conservative voices that once claimed that the existence of a children’s prison in Baghdad was justification alone for regime change in Iraq, and condemned Saddam Hussein as a dark force who tried to own the minds of the children he imprisoned, are largely silent on the issue of forcible separation and imprisonment of children by the Trump administration, their hypocrisy and moral cowardice on display for the entire world to see.

Fifteen years ago, these alleged pillars of American society took it upon themselves to call me out by name on my stance vis-a-vis children’s prisons in Iraq. There isn’t a week that goes by that I don’t reflect on what I heard and saw in Baghdad that day and wrestled with what I could have done about it. Today I am returning the favor, calling out those who either actively support the president’s policies concerning the separation and imprisonment of immigrant children, or have turned a convenient blind eye to these policies, citing “national security.” Look at the pictures of the children crying as they are taken away from their parents, and the images of children locked in cages like animals. Listen to their cries for help. And then either change your position and join the chorus of Americans who are rising in opposition to these policies, or rot in hell, along with Saddam Hussein and all those whom you similarly condemned then for perpetrating the same acts you so callously condone today.

And thanks, Mom, for pushing me to write this.

*

Scott Ritter spent more than a dozen years in the intelligence field, beginning in 1985 as a ground intelligence officer with the US Marine Corps, where he served with the Marine Corps component of the Rapid Deployment Force at the Brigade and Battalion level.