Trump Administration Quietly Adds Foreign Arms Sale to List of “Essential Work”

Buried on the 18th page of a recently updated federal government memo defining which workers are critical during the Covid-19 pandemic is a new category of essential workers: defense industry personnel employed in foreign arms sales.

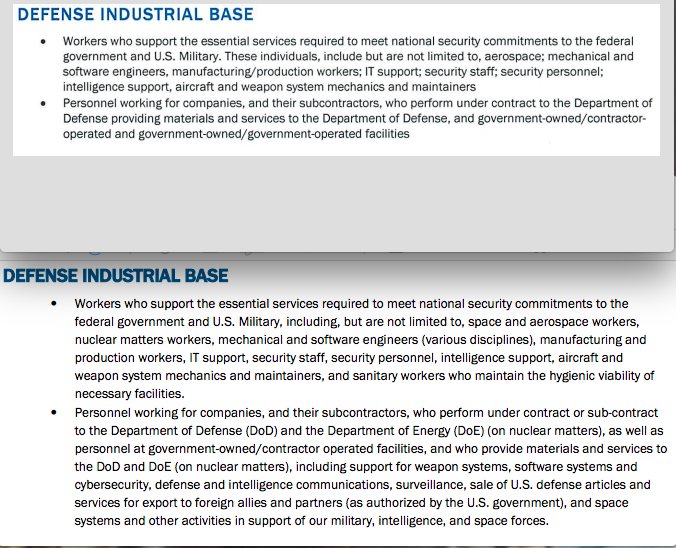

The memo, issued April 17, is a revised version of statements issued by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Department of Defense in mid-March. In those, the defense industry workforce was deemed “essential” alongside healthcare professionals and food producers, a broad designation that prompted criticism from a former top acquisition official for the Pentagon, defense-spending watchdoggroups, and workers themselves. The original March memos made no mention of the tens of billions of dollars in foreign arms sales that U.S. companies make each year.

The new text indicates that the federal government deliberately expanded the scope of work for essential employees in the mid-April memo to include the “sale of U.S. defense articles and services for export to foreign allies and partners.” In These Times spoke with numerous workers who instead say their plants could have shut down production for clients both domestic and foreign. The updated April 17 memo was issued as the United States reported more than 30,000 Covid-19 deaths, a number that would come close to tripling in the following weeks.

The new memo, which says essential workers are those needed “to maintain the services and functions Americans depend on daily,” also reflects what defense workers tell In These Times has been a reality throughout the pandemic: Work is ongoing on military-industrial shop floors across the country, including on weapons for foreign sales.

(A memo in March said essential workers are those needed to “meet national security commitments to the federal government and U.S. military.” In April, the government quietly updated the memo to include a new line of essential work: foreign arms sales.)

Arms manufacturing for export has continued at a Lockheed Martin plant in Fort Worth, which has stayed open 24 hours a day during the pandemic and manufactures the F-35 fighter jet. Asked by In These Times if F-35 production for international customers was ongoing in Fort Worth during the pandemic, a Lockheed spokesman responded that “there are no specific impacts to our operations at this time.” The company has a robust slate of domestic and foreign orders to fulfill for the F-35—the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, one the company now advertises at a price tag of at least $89 million per jet. This slate includes 98 for the United States in the fiscal year 2020 and scores for international buyers in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, according to a recent report on the F-35 program from the Congressional Research Service.

An employee at the Fort Worth plant told In These Times, “I don’t think it should be designated essential if we’re not doing it for our own country. I understand these other countries have put money into it. I do understand that. But these other countries are shut down, too,” the worker added, referring to the major disruptions of economic activities across the globe. The employee said they have seen computer monitors indicating jets were destined for Japan and Australia in recent weeks.

In the first weeks after the country shut down, the employee says they and their fellow workers asked themselves, “Why don’t we move these aircraft out of the way for a minute? And we have enough manpower here we could make masks. We could make ventilators.” But the company’s priorities for its essential workers, the employee says, has been: “Let’s get these jets and let’s get them running. Let’s pump them out the door.”

Several defense industry workers told In These Times they believe on-site manufacturing work at weapons plants for both foreign and domestic use could have been suspended at least for a matter of weeks during the pandemic. They also said they worry about the feasibility of keeping busy workplaces safe and sanitary, and that they distrust employers’ methods for handling virus cases that have emerged among workers.

Alarm over the expectation to continue reporting to shop floors for hands-on jobs has opened a rift between defense contractors and their employees, with the latter feeling constrained from speaking out publicly due to the confidentiality surrounding national security work. Several workers, all concerned about the risks of plants staying open, spoke with In These Times on the condition their names not be published, fearing repercussions or losing security clearances.

Ellen Lord, the Pentagon’s top weapons buyer, said at an April 30 press conference that of 10,509 major companies tracked by the Defense Contract Management Agency, just 93 were closed, while 141 had closed and reopened. While many in the defense industry can work remotely—a Lockheed spokesperson told In These Timesby e-mail that about 9,000 of its 18,000 employees in Fort Worth are telecommuting—the thousands that remain on plant floors, workers say, are often blue-collar employees whose jobs are hands-on. On an April 21 earnings call, outgoing Lockheed Martin CEO Marllyn Hewson told investors that “our manufacturing facilities are open and our workforce is engaged.”

Concern for the safety of that workforce prompted Jennifer Escobar—a veteran and wife of a Lockheed Martin employee in Fort Worth who himself is a disabled veteran—to publicly denounce the company for staying open during the pandemic.

More than 5,000 people have signed her petition calling for the Fort Worth site to shut down and send employees home with pay. A similar petition on behalf of Lockheed Martin employees in Palmdale, Calif., garnered hundreds of signatures. Escobar spearheaded the campaign, she says, for “everybody else who couldn’t stand up because they have a fear of retaliation from the employer.”

Escobar also started a GoFundMe page for the widow of the Fort Worth site’s first reported Covid-19 death. Claude Daniels, a material handler, and his wife, also a Lockheed employee, had together spent about seven decades working for the company, according to the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers union.

The local machinists union reported in late April that the Fort Worth site had 12 confirmed virus cases among Lockheed and non-Lockheed employees. Since the plant has remained open during the pandemic, the company has responded to the outbreak by identifying and informing workers who have been in proximity with an infected employee and asking them to stay home, according to a Lockheed spokesman.

But Escobar and one plant worker said there are gaps in that response. For example, Escobar says there were instances in which a worker was sent home while their spouse, also a company employee, was not, despite the presumably close contact the pair has in a shared living space. One Fort Worth worker also said that while the company will remove an employee who works within six feet of someone who tests positive, there are cases of people who work at greater distances—the employee gave the example of workers on either side of a jet’s wings—who still share items during their shift.

“Even though we were sharing the same workstation, the same computer, the same toolbox, that doesn’t count,” the employee says.

In response to these concerns, Lockheed Martin told In These Times via email,

“Our Facilities teams have increased cleaning schedules within all our buildings and campuses across Lockheed Martin, with a high concentration on common areas like lobbies, restrooms, breakrooms and elevators. Upon learning of probable exposure, a contracted professional cleaning and restoration company sanitizes the employee’s workspace, surrounding workspaces, common areas, and entrances and exits throughout the building.”

Anger at the expectation employees continue working led one to spit on the company’s gate in Fort Worth. Escobar says,

“He was just really upset that the company was treating him like that.”

Lockheed Martin spokesman Kenneth Ross told In These Times that the company’s security team was aware of and investigating the reported spitting incident.

“Obviously, that kind of behavior is not fitting with what we’re trying to do to create a Covid-19 safe environment,” he said.

One Fort Worth employee infected with the virus filmed a video of himself from a hospital bed that went viral and was viewed by many of his coworkers. In sharing his story, he also exposed a gap in the company’s ability to respond to the virus while maintaining its floors open.

In Anthony Melchor’s video, which has been viewed more than 16,000 times, he is interrupted by coughs and wheezy breaths. “I’m cool on my stool, you know me,” he says, warning his fellow workers that “this Covid ain’t no bullshit, man.” He calls on them to sanitize their work areas and not go to work if they feel unsafe.

During a weekend in early April, Melchor, who suspects he was exposed to the virus at work, began to have severe migraines. He woke up the next day in a pool of sweat. His doctor ordered a Covid-19 test, but his first result was a false negative, which Melchor believes happened because his nasal swab was too shallow. After several days passed and his condition worsened, his wife insisted he receive medical attention. A second coronavirus test then came back positive, he said.

Melchor says his delay in informing Lockheed that he was positive for the virus also meant his coworkers were delayed in being removed from the line. Asked whether workers are removed from the plant when an employee shows symptoms of the virus or only after one has tested positive, a Lockheed spokesman wrote that the company “identif[ies] and inform[s] any employees who interacted with individuals exposed to or diagnosed with Covid-19 while maintaining confidentiality.”

At a Lockheed Martin site in Greenville, S.C., where the company is currently producing F-16s for Bahrain—the company appears to have only foreign clients for the fighter jet—one employee expressed concern over how close workers get to one another when they often work in pairs on either side of a jet. The worker also says it is “the nature of our business” to have employees who frequently travel, including out of the country, leading the worker to fear what they may bring back to the workplace when they return.

“From a financial standpoint I know it’s not beneficial for us to be at home,” the Greenville worker says, “but the safety of employees to me should be most important.”

Lockheed’s fighter jets are among many defense products that U.S. companies export.

In addition to Lockheed Martin, In These Times submitted questions to three other defense firms about ongoing exports during Covid-19. Northrop Grumman announced in its April 29 earnings call that the company had delivered two Global Hawk surveillance drones to South Korea that month. Asked about the precautions the company took for the safety of workers handling the drones in the final weeks leading up to the April delivery, a spokesperson wrote that the company is “taking extraordinary measures to maintain safe working conditions.” The U.S. ambassador in Seoul tweeted a picture of the sleek gray drone emblazoned with Korean letters in an April 19 message congratulating those involved in its delivery.

Another contractor, Wichita-based Textron Aviation, told In These Times that, during Covid-19, the company “will continue to support our customers according to our funded contract requirements, which includes foreign customers.”

Jeff Abramson, a senior fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Arms Control Association, says the pandemic does not appear to have caused any “deviation” from the Trump administration’s policy of promoting foreign arms sales. He notes that the State Department approved numerous potential sales, including ones to controversial clients like the United Arab Emirates and the Philippines, in the midst of the global pandemic.

“It certainly seems that this administration is trying to get a message to industry that you are important. There will be work for you,” Abramson says.

Despite the essential designation, some Boeing defense-industrial sites buckled under pressure as the virus spread and closed during the pandemic. A day after the death of an employee infected with the virus in Washington State, Boeing announced it would shutter its Puget Sound site, where some 70,000 people work on both commercial and defense aircraft. Boeing also shut down a Pennsylvania site that produces military aircraft for two weeks, saying the step was “a necessary one for the health and safety of our employees and their communities.”

When Boeing partially reopened Puget Sound after about three weeks, the first production it resumed was on defense products. Asked if work was underway on P-6 patrol aircraft for foreign clients such as South Korea and New Zealand, a company spokesperson responded, “We are evaluating customer delivery schedules and working to minimize impacts to our international customers.”

Unlike the United States, some countries have allowed defense production to shut down. Mexico did not declare its defense industry essential, prompting a rebuke from the Pentagon’s Ellen Lord, who wrote to the Mexican foreign ministry regarding interruptions to supply chains. Lord later said she had seen a “positive response” from Mexico on resolving the issue. F-35 facilities in both Japan and Italy shut down for several days in the early weeks of the pandemic.

Melchor, the Fort Worth employee who is now recovering from Covid-19 at home, says he agrees with the defense-industrial base’s designation as essential, including when that involves commitments to customers amongst U.S. allies. “I just also believe that our customers would have understood if there was a two-week delay or even a month delay because of this virus,” he says.

He believes leadership is needed to address the issue in a unified way and says debate about the crisis amongst workers, whom he called on in his video to “pull together,” has become fractious.

“What I found interesting is the very thing that we build [is] to serve and protect, foreign and domestic, to protect us from any type of evil or wrongdoing,” Melchor says. “At what point does our company protect us?”

An original version of this story said that U.S. companies make foreign arms sales in the order of $180 billion a year. While the U.S. State Department says that the U.S. government manages the transfer of approximately $43 billion in defense equipment to allies each year and provides regulatory approvals for more than $136 billion per year in defense sales abroad, others estimates of the volume of U.S. arms sales abroad have differed. A new report from the Center for International Policy says that the United States made at least $85.1 billion in arms sales offers in 2019. The report’s authors call this figure “a floor, not a ceiling” and said the number is “almost assuredly an undercounting” due to lack of transparency in arms sales reporting.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.