Tracing the History of The Partitioning of Iraq

Dividing Iraq – From Op-Eds, To News, To Truth

Readers of newspapers in 2017 might not remember a time in which they haven’t read about an ongoing war in Iraq – the Iran-Iraq war persisted throughout the 80s, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the Gulf War, and ongoing US bombings reigned throughout the 90s, and the US intervention and the Iraqi civil war that followed ran throughout the first decade of the new millennia.

The imaginary of Iraq in the mind of a common reader of newspapers, Western or Middle Eastern, therefore depicts Iraq as a country in which violent conflicts are widespread, especially when fighting involves its three main ethno-sectarian groups: Iraqi Kurds, Iraqi Sunnis, and Iraqi Shiites. With regards to the internal conflict in Iraq, which has been amplified since 2006, we now talk of partitioning Iraq into three independent states, one for each ethno-sectarian group. This logic of division is however an anomaly: the Middle East has been ripped by several civil conflicts, and yet Iraq is singled out when it comes to the idea of partition. Where has this idea of dividing the sovereign state of Iraq come from? This question is the premise of my attempt to draw a timeline of the partition narrative in both Western and Middle Eastern media. My findings could ultimately help argue against partitioning Iraq, especially if the idea itself serves not the demands of the Iraqi people but foreign interests instead.

I – The First Call for Partition: by Gelb and Biden, from Washington (Post) and New York (Times).

2003

One of the earliest sources I have been able to find online in both Western and Middle Eastern media referring to Iraq’s partition narrative is penned on the 25th of November in 2003 by Leslie H. Gelb, former columnist for the New York Times. The Op-Ed for the newspaper comes months after the USA’s intervention in Iraq, and the writer proposes a “three-state” partition plan by highlighting the conflict’s cause, situation and solution.

Gelb argues that the commitment to a unified Iraq is a “fundamental flaw” because this unity is based on borders “artificially made.” Such artificiality comes in reference to Iraq’s colonial past and British-French treaties such as Sykes-Picot, which, divided the Middle East into British and French mandates after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

The correspondent also placed his proposal within the political climate of US foreign policy in 2003. The division of Iraq indeed curbed the ambitions of “troublesome and domineering Sunnis” that would be “left without oil revenues.” A unified Iraq was no longer “necessary to counter anti-American Iran.” Finally, the model of the Kurds’ autonomy showed no political repercussions since “Ankara has lived with [it].”

Finally, Gelb calls for the US to “correct the historical defect” by “mak[ing] self-governing regions with boundaries drawn as closely as possible along ethnic lines.” With such new borders, the writer believes Iraqis must be given “time [to] go to south or north Iraq,” depending on their ethnic or sectarian identity.

The deconstruction of Gelb’s arguments is necessary since his piece for the New York Times is to become the first widely read reference for subsequent media sources about partitioning Iraq. While Gelb finds historical legitimacy for his proposal with his firm claim that Iraq is “artificially made,” he fails to acknowledge that what he reveals as truth is in fact still debated among scholars today. Sara Pursley’s article for Jadaliyya, highlighting the entwined histories of the old provinces of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra and revealing the existence of a concept of Iraq in pre-colonial times, diminishes the starting point of Gelb’s partition plan.

Gelb’s reasoning, too, is problematic, especially since he ties the narrative of dividing local Iraqis with American interests and foreign policies, which constitutes not only a limited Western view on Middle Eastern affairs but also further confuses political interests foreign to Iraq with apolitical Iraqi identities.

Finally, Gelb’s solution of re-drawing Iraq’s borders “as closely as possible along ethnic lines” and his guarantee for travelers between the southern and northern parts of the country fail to consider the danger of ethnic cleansing, inevitable as per international law in Iraq’s case with the descriptions he provides, and ignore the impracticality of such a transfer of people, as seen with the partition between India and Pakistan. The latter partition was also rooted in a sectarian divide and the lessons learned from the mass migrations entering Pakistan and India are the “many hundreds of thousands [that] never made it.”

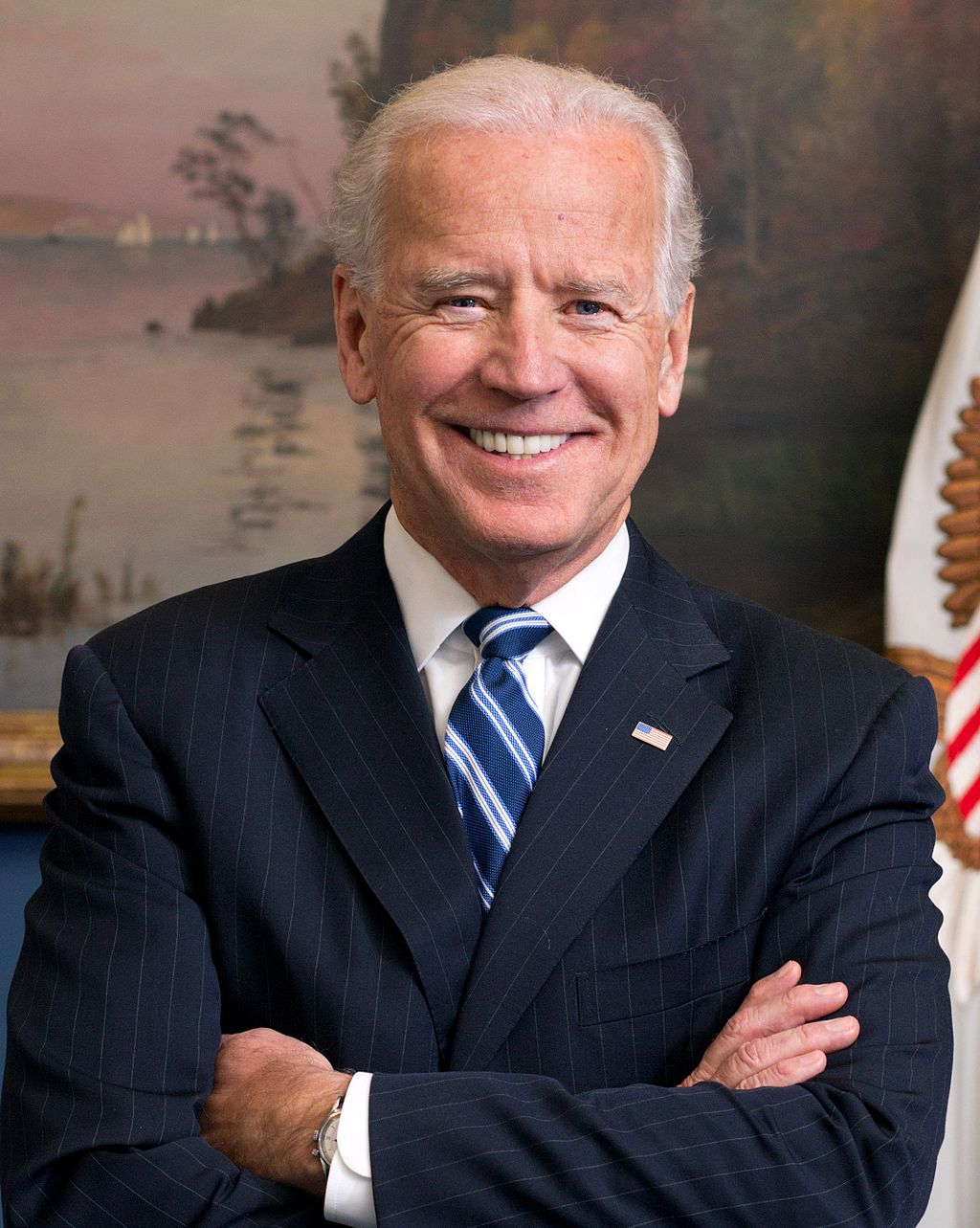

One of the first widely read media sources about partitioning Iraq is therefore flawed and may not effectively serve as a methodical starting point to consider the division of a sovereign country. Gelb’s ideas, however, are to inspire three years later another key figure in American affairs to call once again for Iraq’s partition – Joe Biden.

2006

In an opinion piece for the Washington Post in August 2006, Biden (image below) lays out a five-point plan as a solution to Iraq’s situation.

Unlike Gelb, whom he nevertheless mentions in the beginning of his piece, Biden highlights different problems in Iraq, which give him reason and legitimacy for his plan. Such problems are the last Iraqi election, during which “90 percent of the votes went to sectarian lists,” a failed rule of law under the grip of “ethnic militias,” and “massive unemployment.”

The main goal of the plan aims to “give Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds incentives to pursue their interests peacefully” by “decentralizing” and splitting Iraq into three regions. Biden also claims his “plan is consistent with Iraq’s constitution,” and he specifies that constitutional laws already provide Iraq’s different provinces the right measures “to join together,” a claim that suggests a present will in Iraq for division.

Biden’s detailed five-point plan recognizes difficulties with partition but nevertheless fails to provide legitimate reasons for dividing Iraq. Interestingly, Biden’s concern for local Iraqi matters such as elections, the law, and unemployment, might be deemed as admirable, but the lack of contextualization of these problems reveals a naïve understanding of Iraqi affairs from the former chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Indeed, although favoring sectarian lists is telling of ingrained sectarian bias among Iraqis, this way of electing is nevertheless popular in other countries with multiple sectarian groups, such as Lebanon, a country that nevertheless does not cede to partition ideas. The division of Iraq into countries, and therefore three armies, could help eradicate “ethnic militias,” but Biden’s solution comes only because the Bush administration, the one he writes to, dismantled the Iraqi army entirely.

What is therefore astonishing about Biden’s piece is its erasure of any American responsibility in Iraq’s problems; he talks about civil war, dissent, internal violence, but never contextualizes nor acknowledges the effects of American troops in Iraq. Indeed, Biden’s will to turn a blind eye on the impact of the US intervention in Iraq only three years earlier serves his portrayal of a self-destructive Iraq.

Biden’s most interesting argument, however, and perhaps the most compelling, is the Iraqi backing he finds for his plan with the example of the Iraqi constitution. A year after Biden’s piece, Reidar Visser’s “The Western Imposition of Sectarianism on Iraqi Politics” warns that

“the US administration intended to weaken Iraq by manufacturing sectarianism and encouraging schisms.”

Biden has indeed forgotten that the Iraqi constitution of 2005, “co-written by US experts,” is among such efforts pointed by Visser, notably by “open[ing] the door for the idea of federalism and a possible future division.”

The second prominent media source – also Western – is as flawed the first; Biden’s solution resonates loudly in a special context with the beginning of the US’s promised withdrawal from Iraqi soil in 2007. This event fuels not only Americans’ rush into fixing Iraq before departure, but also their plan for its partition, a rush effectively demonstrated with a cluster of Western media sources following Biden’s piece, between 2006 and 2007, which, finally, have equivalent Middle Eastern media sources about dividing Iraq.

II – Partition In Motion: From Op-Eds to News

On September 6, 2006, the New York Times published “Shiites Push Laws to Define How to Divide Iraqi Regions” a news piece about new efforts by Abdul Aziz Al-Hakim, a Shia political leader, to call for division in Iraq. This call by the political leader had been covered by Iraqi media Buratha News Agency a month earlier, on August 6, with a news piece entitled in Arabic “An increase in voices backing Al Hakim’s call for establishing provinces of center and south Iraq.”

The contrast between these two corresponding articles is interesting. The New York Times reporter dwells significantly on the tensions between Sunnis and Shias, including a history of the conflict between the two, and a supposed ongoing debate about dividing the country. The “anger[ed] Sunnis,” “sectarian executions,” “crimes of rape and murder,” and “perpetual oil shortage” are few of the many images the article draws upon to find hope in Hakim’s call to “breaking the country into autonomous regions.”

Interestingly, the Buratha news piece about the same call for division does not share the same perspective as its Western equivalent. Indeed, while the New York Times places on a pedestal the idea of division, or at least, for the time being, federalism, Buratha news is unable to define this idea of breaking up the country. It chooses to use the word “province” instead of “federal state” for its title, and when it does bring forth the word of “federalism” in Arabic – only through Al Hakim’s tongue – it makes sure to highlight immediately after that “federalism does not whatsoever imply division.” The Iraqi news does recap the war-torn state of Iraq, but instead of using this premise to justify dividing Iraq, as the New York Times has done, it finds in Hakim’s call a “temporary” solution.

The careful tone in the Buratha news piece therefore, in contrast, exposes the zeal found in the New York Times with the idea of dividing Iraq. In fact, the Buratha piece acknowledges the newness of the concept of federalism, “which Iraqis are trying to educate themselves about,” and this contrast comes as no surprise because federalism is after all a concept born in the West, and the New York Times fails to see the impracticality of applying federalism (or complete division, which it seems to be rooting for) in Iraq’s case.

The Western media’s failure is once again one of perspective, assumptions and over-assurance, which becomes dangerous because we are now dealing with news pieces and not Op-Eds. According to the Time magazine in November 2006, the division of Iraq “has already happened.” The wheels of division are indeed already in motion, at least in the perspective of Western media, which reports about Iraq’s conflict from a supposed ‘objective’ distance, and which continues in 2007 with a new set of articles about division, ones that will now not only echo Middle Eastern media but stir them, as well.

2007

On September 26, 2007, Joe Biden’s plan to divide Iraq, published in 2006, and inspired by Gelb’s piece of 2003, was presented to the Senate for approval – and received it. The endorsement was covered by both the Washington Post and Al Jazeera, on the same day. The comparison between these two news pieces is once again telling of the disparity in interests and direction between Western and Middle Eastern media.

The Washington Post reports the endorsement as a success, a “rare bipartisan consensus,” a “political settlement for Iraq that would divide the country.” The newspaper guarantees, once again, that the structure of Biden’s plan is “spelled out in Iraq’s constitution.” Finally, without dwelling on the importance of the division for taming Iraq’s political turmoil, the piece focuses on why Americans “can’t walk away from Iraq” and make “all [their] sacrifices irrelevant.” It describes the endorsement as a “significant milestone.”

The Al Jazeera news piece is very interesting in contrast with its American equivalent. The title of the piece, in fact, is telling, “The Plan to Divide Iraq – Non-Binding but Coming.” Indeed, the distance found in the title reflects the narration of the news piece; whereas a reader of US media would assume to find the same zeal about partition in Middle Eastern media, supposedly a “significant milestone,” there is no mention whatsoever in the source of the importance of the plan or its relevance for Iraq. The Al Jazeera reporter dwells on how important the resolution is for American politics, notably the revealed division among Republicans “because interestingly 26 Republican Senators voted against the endorsement,” or what effect the endorsement has for “Biden’s plan for running for office.” Interestingly, at the end of the piece, the writer includes a recap of the Bush administration’s work in Iraq, especially how the administration, under Paul Bremer, “sought to create a ‘new Iraq’ on a sectarian basis.” The Al Jazeera piece, notably, does not acknowledge whether Bush’s efforts to manufacture sectarianism has been effective or influential in dividing the country. The word ‘partition,’ in fact, is only written when reporting about the Senate’s endorsement.

It is eye-opening to observe that Western media has hailed the approved plan to divide Iraq as a “significant milestone” whereas Middle Eastern media, once again, is not even lucid of the practicality of any division of the kind. But while we could infer about Al Jazeera’s distance from the partition narrative in its description of its impact on American politics, not Iraqi, an article on Al Arabiya published four days later reveals a bigger disparity between Western and Middle Eastern media, and between Western and Middle Eastern politics. The title of the piece comes indeed as no surprise… “Only Kurds Support U.S. Partition Idea.” What was a diplomatic “The Plan to Divide Iraq” for Al Jazeera has indeed become, after Al Arabiya’s referral to “leading Sunni and Shia authorities” about the idea of dividing Iraq, which they rejected, a truly foreign “US Partition Idea.”

III – Partition Complete: From News to Truth

2014

The year 2014 marks the rise of two terms recurrently used in both Western and Middle Eastern media in relation to Iraq: ISIS and division. This paper has indeed showed that the former is not the cause of the latter, given the (short) history of the partition narrative, but the rise of ISIS has nevertheless influenced talks for dividing Iraq. In July 2014, a month after ISIS’s invasion of Mosul, in Iraq, CNN published, with no hesitation, the news piece entitled “Iraq to split into three: So why not?”

Regardless of the firm tone of the title, it is the content of the article that is critical. Indeed, the CNN piece, after ISIS’s capture of Mosul and their earlier proclamation of an Islamic State across the Syrian-Iraqi border in January 2014, lays out all the arguments for dividing the country, and it comes as no surprise that they have mentioned “Gelb’s Op-Ed” and “Biden’s plan” – from which they get credence. CNN dwells on the geo-politics of Iraq, and how ISIS is now re-drawing the borders of Iraq, but it is the final sentence of the news piece that becomes the centerpiece of their arguments for a divided Iraq:

“Some historians argue that Iraq was never really a country anyway, more a colonial confection like British India, and we are now seeing the inevitable consequences.”

Despite my contestation of the many arguments for the partition of Iraq, whether they related to the practicality of re-drawing borders, the (un)popularity of the narrative among Iraqis, or the artificiality of the state of Iraq, the fatalistic tone of CNN’s piece is more powerful, especially with their use of the artificial state narrative, which makes the co-existence between Iraqis a case that wasn’t meant to be, an unnatural unity weak at its core.

“Iraq has gone beyond the point of keeping Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds under one roof,” claims the reporter for the Huffington Post, in a piece published in the summer of 2014, a month apart from the CNN article.

Indeed, a general consensus of the intolerance of Iraqis has been reached among Western media, and what makes this consensus even more dangerous vibrates in the title of the Huffington Post article: “Why It’s Time For Iraq to Split Into Three Countries.” The shocking aspect of this title is not the resolve of the tone, but truly the way it ignores the carefulness of past media sources to qualify the division of Iraq – there are no references of ‘regions,’ or ‘semi-autonomous states,’ nor ‘autonomous federal states,’ as I have noted in previous articles. This jump from regions to countries could well be a mistake or exaggeration from the newspaper, but nevertheless a crucial one.

The crucial repercussions of Western news pieces in relation to Iraq’s division, from the CNN and Huffington Post, or early on with the New York Times and the Washington Post, lie not only in how they influence Iraq’s imaginary for the American reader but also how they critically influence Middle Eastern media and their perception of Iraq.

In June 2016, Al Jazeera published the news piece about Masrour Barzani’s call for “dividing Iraq after defeating ISIS”. The prominent member of the Kurdistan Democratic Party has been vocal about partition talks, which, as noted in Al Arabiya’s piece in 2007, had been exclusive to Iraqi Kurds.

But, Al Jazeera, surprisingly, marks a shift in this perception with the claim in the article that the Kurds’ dream for independence is also shared by a “majority of Shiites since disposing of Saddam Hussein in 2003.” Furthermore, the comparison of Al Jazeera’s headlines between 2007 and 2016 is telling of this odd shift in partition discourses: we have jumped in 2007-2010 from Al Jazeera articles such as “Dividing Iraq in America’s Mind,” “(Shia) Tribes in South Iraq Reject Partition and Demand End of Occupation,” and “Rejecting The Establishment of a Sunni Region,” to 2016 with, somehow, a “majority of Shiites” demanding independence.

One could argue that the shift noted above simply reflects one author’s view, and not those of many at the news agency. That said, a search of the terms “Dividing Iraq” (in Arabic) on Google Trends proves otherwise. The online tool tracks the popularity of Google searches across time by quantifying the results on a scale of 0 to 100; a value of 100 represents the peak popularity for the term and a score of 0 means the term was less than 1% as popular as the peak. The results for “Dividing Iraq” in Arabic are compelling: the scores for the period 2004-2007 fluctuate between 0 and 39, for 2008-2014 from 0 and 23 and, for 2014, from 5 to 68, and for 2015, remarkably, from 8 and 100. The results not only prove that the idea of dividing Iraq was not at all popular among Arabic-speaking Google users, but they also reflect how the same idea suddenly trended in the years after 2014 among more and more Arabic-speaking Google users, who are in many numbers people living in the Middle East – and follow news agencies like Al Jazeera. The rise of ISIS in 2014 could explain the interest of Middle Easterners in the division of Iraq, but what we cannot disregard about such interest is its sudden nature. Indeed, how is the turmoil caused by ISIS since 2014 any different than the rise of sectarian conflict in 2006 and 2007, a time in which Middle Eastern media such as Al Jazeera, and Arabic-speaking Middle Easterners, did not seem at all interested in partition ideas about Iraq?

A few years, evidently, could not have been enough to shift the Shia’s or Sunni’s consciousness of a united Iraq – for decades, even centuries, the Abbasids, the Ottomans and the British persisted and failed at this endeavor. But what such empires lacked in their efforts to ‘divide and conquer’ is a strong press that influences the perception of states, from without and within. It is precisely in this way of changing perception, from Gelb and Biden’s Op-Eds, to Western then Middle Eastern news headlines, to universal and fatal truth, that the US has found perhaps the greatest weapon of mass destruction in Iraq.

Conclusion

The timeline I have drawn is in no way representative of the ethno-sectarian divide between Iraqis. The findings, after all, are superficial in that they are Op-Eds and news articles written in offices far away from Iraq’s conflict. But then again these headlines find importance in that superficiality – readers from the US and the Middle East can only observe the Iraqi conflict from the surface of headlines, news articles and opinion pieces. As a result, when Gelb and Biden, from 2003 to 2006, have depicted Iraq as the ailing mother of Jacob and Esau, a country in which its own sons irreconcilably fight, their depiction, as flawed and misconstrued and bias as it is, becomes an image engraved in the consciousness of their readers. When the US media exhausts its entire arsenal of presses, from the New York Times, to the Washington Post, to the Time Magazine, to CNN, to the Huffington Post, their blow against the nature of the Iraqi state and the relations between Iraqis is bound to echo with as much resonance in the studios of Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya. This echo is after all the danger of the westernized society we have reached; a journalist in Iraq speaking a foreign language, often, is considered more credible than one speaking the same mother tongue as the fighters in conflict. The aim of this paper, however, is not to see whether or not the US intently sought to ingrain the idea of partition in Iraqis. The evolution of the partition narrative, indeed, highlights the incredible power of media not politics in shaping the fate of states and people. This power should be regarded as much as a curse as a blessing, perhaps because one can find through the mythmaking process of dividing Iraq the reverse way back to unity.

Rayyan Dabbous is a Lebanese author and playwright. He is the writer of Bad Men (Arab Scientific Publishers, 2015) and writer-director of Up For Grabs America (Medicine Show Theatre, 2017). His research at New York University focuses on communication in media and entertainment industries, particularly in the Middle East.

References

Gelb, Leslie H. “The Three-State Solution.” The New York Times. 23 November 2003.

Pursley, Sara. “Lines Drawn on an Empty Map: Iraq’s Borders and the Legend of the Artificial State.” Jadaliyya. June 02 2015.

Biden, Joe. “A Plan to Hold Iraq Together.” The Washington Post. 24 August 2006.

Al-Rawi, Ahmed K. Media Practice in Iraq. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Oppel Jr, Richard A. “Shiites Push Laws to Define How to Divide Iraqi Regions.” The New York Times. 6 September 2006.

“Tasaod Al-aswat fi Taiyid Daawat Al-Sayed Abd El-Hakim Biikamat Iklim Alwasat wa Al-Janoub.” Buratha News Agency. 6 August 2006.

Galbraith, Peter W. “The Case For Dividing Iraq.” The Time Magazine. 5 November 2006.

Murray, Shailagh. “Senate Endorses Plan To Divide Iraq.” The Washington Post. 26 September 2007.

Aloush, Ibrahim. “Khotat Takskim AlIraq.” Al Jazeera. 26 September 2007.

“Only Kurds Support US partition idea.” Al-Arabiya. 30 September 2007.

Nuri, Ayub. “Why It’s Time For Iraq To Split Into Three Countries.” Huffington Post. 16 June 2014.

Lister, Tim. “Iraq to split in three: So why not?” CNN. 8 July 2014.

“Al-Barzani Yadou Ila Taksim AlIraq Baad Alkadaa Ala Tanzim Al-Dawla.” Al Jazeera. 16 June 2016.

“Taksim Al-Iraq Fi Alfekr Al-Ameriki.” Al Jazeera. 28 September 2007.

“Ashaer Janoubi AlIraq Tarfod Altaksim Wa Toutaleb BiInsihab AlIhtilal.” Al Jazeera. 8 December 2007.

“Rafd 3irai LiInshaa Iklim AlSunna.” Al Jazeera. 28 November 2010.

Darlymple, Williams. “The Great Divide.” The New Yorker. 18 February 2015.