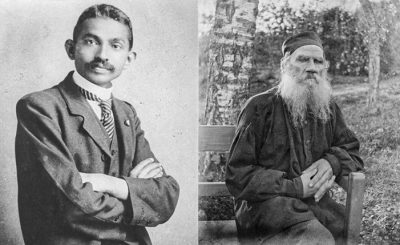

Truth and Nonviolence, Tolstoy and Gandhi: Light as Darkness Approached

“We possess a single infallible guide, the Universal Spirit that lives in men as a whole, and in each one of us, which makes us aspire to what we should aspire: it is the Spirit that commands the tree to grow toward the sun, the flower to throw off its seed in autumn, us to reach out towards God, and by so doing, become united to each other.” — Leo Tolstoy (9 Sep1828 – 20 Nov 1910)

November 20 marks the death of Leo Tolstoy in 1910 when he left his estate Yasnaya Polyana and walked to a railroad station at Astopovo, a journey with no set destination. As Isaiah Berlin writes at the end of his well-known essay on Tolstoy’s philosophy of history, The Hedgehog and the Fox:

“At once insanely proud and filled with self-hatred, omniscient and doubting everything, cold and violently passionate, contemptuous and self-abasing, tormented and detached, surrounded by an adoring family, by devoted followers, by the admiration of the entire civilized world, and yet almost wholly isolated, he is the most tragic of the great writers, a desperate old man, beyond human aid, wandering self-blinded at Colonus.”

Yet the darkness of the final two years of Tolstoy’s life was enlightened by his written contacts with Mohandas Gandhi (not yet called Mahatma). Gandhi had read Tolstoy’s fundamental spiritual-political work The Kingdom of God is within You. Shortly after it was published in English in 1893 and had been much moved by it. Gandhi had his friends translate the book into his native language, Gujarati.

Gandhi had read earlier in London Helena Blavatsky’s The Voice of Silence, published in 1889, which elaborated the doctrine of liberation through service to others with the Buddhist concept of bodhisattva — the enlightened being who postpones indefinitely entry into nirvana in order to serve others. The voice of the silence is the inner voice of the Higher Self or the soul. There is also developed the idea ‘to render good for evil’.

Thus Gandhi was well prepared to react positively to Tolstoy’s vision even if the vocabulary was largely Christian. Christ’s teaching, writes Tolstoy, differs from other teachings in that it guides humans not by eternal rules but by an inward consciousness of the possibility of reaching divine perfection. Tolstoy stresses the Middle Way, which led the French writer E.M. de Vogue to write that Tolstoy had the soul of an Indian Buddhist. Tolstoy had discovered that nonviolence must have a spiritual foundation, most clearly expressed for him in the Gospels.

Leo Tolstoy and Gandhi never met, but they corresponded with each other during the final two years of Tolstoy’s life, 1909 and 1910. Tolstoy had read Hind Swaraj (1909) where Gandhi set out his vision of a liberated India, the means to reach liberation, and what an independent India could mean for the world. It was Gandhi’s plan of action before he set out to put it in practice. Gandhi had listed some of Tolstoy’s books in a list of supplementary readings to Hind Swaraj in particular The Kingdom of God is within You and Letter to a Hindoo, Tolstoy’s reply to an Indian revolutionary who had proposed a violent uprising.

Tolstoy wrote to Gandhi:

“I read your book with great interest because I think that the question you treat in it — the passive resistance — is a question of the greatest importance not only for India but for the whole humanity.”

Tolstoy had also read Joseph Doha’s 1909 biography of Gandhi An Indian Patriot in South Africa, the first biography of Gandhi to be written. In August 1910, Gandhi wrote to Tolstoy to announce the creation of his ashram in South Africa called Tolstoy Farm.

Gandhi’s efforts in South Africa were signs to Tolstoy that nonviolence based on the importance of personal virtue could be put into practice. Much of the last years of Tolstoy’s life was a harsh struggle against darkness as represented by the State, its war-making power, its ideologies, and the social thinking that structured the State. Colonialism, imperialism and the oppression of the indigenous races were the hallmark of the State. He saw the forces at work that would lead to the First World War and the Russian Revolution. By 1901 he had been excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church — not that he expected much light to come from Church-State relations. The Church did insist that no prayers be said at Tolstoy’s funeral.

For Tolstoy as for Gandhi, nonviolence was an expression of ‘soul force’ — the outward expression of the Inner Kingdom.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Featured image is from The Transnational