Time to Stop Sending Canadian Troops to Haiti

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

During times of instability in Haiti, progressives both in the Caribbean nation and abroad often fear impending US military intervention. This makes sense, given Washington’s long history of deploying soldiers to shape Haitian affairs.

Since President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated Wednesday the Haiti Information Project has reported that combat vessel USS Billings is in Santo Domingo on the other side of the island. They also published photos of two US C-20 military aircraft unloading passengers and gear at the Toussaint Louverture Airport in Port-au-Prince. A video appears to show plainclothes men, reportedly Special Forces, being met by US embassy representatives.

But, what about Canadian Forces? While I have yet to find evidence of any Canadian deployment, it’s important for progressives to be vigilant considering this country’s history of using or threatening to use force to influence Haitian politics.

Amidst a February 2019 general strike that nearly toppled Moïse, heavily-armed Canadian special forces were videoed patrolling the Port-au-Prince airport. The Haiti Information Project suggested that they helped family members of Moïse’s corrupt, repressive and unpopular government flee the country.

On February 29, 2004, JTF2 commandos took control of the airport from which Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide was bundled (“kidnapped” in his words) onto a plane by US Marines and deposited in the Central African Republic. According to AFP, “about 30 Canadian special forces soldiers secured the airport on Sunday [Feb. 29, 2004] and two sharpshooters positioned themselves on the top of the control tower.” Reportedly, the elite fighting force entered Port-au-Prince five days earlier ostensibly to protect the embassy. The JTF2 deployment was part of the Canada/France/US campaign to destabilize and overthrow Haiti’s elected government. According to the military’s account of Operation PRINCIPAL, “more than 100 CF personnel and four CC-130 Hercules aircraft … assisted with emergency contingency plans and security measures” during the week before the coup.

For the five months after Aristide was ousted five hundred Canadian soldiers joined US and French forces in protecting Haiti’s foreign installed regime. A resident of Florida during the preceding 15 years, Gerard Latortue was responsible for substantial human rights violations. There is evidence Canadian troops participated directly in repressing the pro-democracy movement. A researcher who published a report on post-coup violence in Haiti with the Lancet medical journal recounted an interview with one family in the Delmas district of Port- au-Prince: “Canadian troops came to their house, and they said they were looking for Lavalas [Aristide’s party] chimeres, and threatened to kill the head of household, who was the father, if he didn’t name names of people in their neighbourhood who were Lavalas chimeres or Lavalas supporters.” Haiti and Afghanistan were the only foreign countries cited in the Canadian Force’s 2007 draft counterinsurgency manual as places where Canadian troops participated in counterinsurgency warfare. According to the manual, the CF had been “conducting COIN [counter-insurgency] operations against the criminally-based insurgency in Haiti since early 2004.”

After a deadly earthquake rocked Haiti in 2010 two thousand Canadian troops were deployed while several Heavy Urban Search Rescue Teams were readied but never sent. According to an internal file, Canadian officials worried that “political fragility has increased the risks of a popular uprising, and has fed the rumor that ex-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, currently in exile in South Africa, wants to organize a return to power.” The government documents also explain the importance of strengthening the Haitian authorities’ ability “to contain the risks of a popular uprising.” To police Haiti’s traumatized and suffering population 2,050 Canadian troops were deployed alongside 12,000 US soldiers and 1,500 UN troops (8,000 UN soldiers were already there). Even though there was no war, for a period there were more foreign troops in Haiti per square kilometer than in Afghanistan or Iraq (and about as many per capita).

Canadian soldiers were part of the UN mission in the country between 2004 and 2017. A handful of Canadian military officials filled senior positions in the MINUSTAH command structure, including Chief of Staff. 34 Canadian soldiers were quietly dispatched to Haiti during the final six months of 2013.

Canada’ military involvement in Haiti dates to the previous century. Canadian troops joined the US led operation immediately after 20,000 troops descended on the country in 1994. Afterwards Canada took command of the UN force and about 750 Canadian soldiers were on the ground. At a 1996 NATO summit Prime Minister Jean Chrétien was caught on an open microphone saying, “he [US President Bill Clinton] goes to Haiti with soldiers. The next year, Congress doesn’t allow him to go back. So he phones me. Okay, I send my soldiers, and then afterward I ask for something in return.”

According to the 2000 book Canadian Gunboat Diplomacy, Canadian vessels have been sent to Haiti on multiple occasions. In response to upheaval in the years after Jean Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier fled Haiti warships were deployed in 1988 and 1987. Another vessel was deployed in 1974. This time, reports military historian Sean Maloney, “Canadian naval vessels carried out humanitarian aid operations to generate goodwill with the Haitian government so that Haiti would support Canadian initiatives in la Francophonie designed to limit French interference in Canadian affairs.”

As Francois ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier’s first mandate came to an end in May 1963, the country was gripped with upheaval.When Haitian military officers accused of plotting against Duvalier fled into the Dominican Embassy in Port-au-Prince there was a major diplomatic incident between Duvalier and Dominican President Juan Bosch. Fearing forces sympathetic to Cuba may take advantage of the instability to grab power, HMCS Saskatchewan, a British vessel and seven US warships approached Haiti’s coast (three other Canadian ships stood by). The next year HMCS Saskatchewanwas again sent to Haiti to ensure Duvalier did not move towards Cuba.

‘Canada’ intervened militarily in previous centuries as well. In November 1865 HMS Galatea bombed Cap-Haitien in support of a Haitian political leader battling an opponent. Based in Halifax and Bermuda, the British frigate was part of the Empire’s North America and West Indies Station. Two decades later Halifax based HMS Canada was dispatched to Haiti on two occasions over six-months.

British/Canadian forces also sought to crush the Haitian slave revolution. Britain’s primary naval base in North America, Halifax played its part in London’s efforts to capture one of the world’s richest colonies (for the slave owners). Much of the Halifax-based squadron arrived on the shores of the West Indies in 1793 and a dozen Nova Scotia privateers captured at least 57 enemy vessels in the West Indies between 1793 and 1805. A number of prominent Canadian-born (or based) individuals fought to capture and re-establish slavery in Saint Domingue (Haiti). First Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, led the British invasion of Saint Domingue in 1796. As Governor, Simcoe re-instated slavery in areas he controlled.

Canada has a long history of intervening militarily in Haiti. Amidst the current instability, we should seek to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

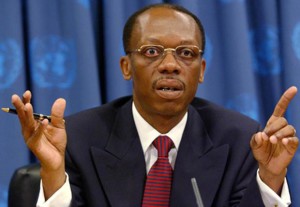

Featured image is from Yves Engler