Thoughts on Nature and Humanity

When rumors of sightings of the ivory-billed woodpecker surfaced around spring 2006, the Nature Conservancy decided to girdle to death about three trees per acre near the bird’s potential habitat in an Arkansas swamp. The idea was to introduce some dying trees in a relatively young forest. This girdling of trees, although inspired by beavers, would never involve these gentle creatures because, all around the area, the beavers were being killed and their influence removed from the landscape. This brought to mind the notion that there is as much human arrogance in conserving as in ravaging nature. We are destroyer and creator. We reserve our absolute right to be gods, and this might well kill us all.

Is conservation a nostalgic wish to return to an America untouched by Europeans? This would hardly be possible without reducing the population to 16th century levels and forsaking most of the technological crutches of the last five centuries. The idea of conservation ought to be replaced by a desire to achieve a state of maximum ecological complexity, in which as many niches as possible may be filled. Consider a fish tank, with its bottom feeders, like the suckers and catfishes, and the middle and top feeders. A balance leads to a tank that stays clean with little input of human energy.

So-called foreign or invasive species can then be seen for what they are: creatures who have discovered and exploited an ecological vacuum. Nature is dynamic and cannot be conserved. Rivers shift their courses. One native parrot species disappears and a new one migrates into its place, just as the American dream, shorn by the wealthy and complacent American-born children, is continually renewed by new flocks of starry-eyed immigrants. The niches are not necessarily comfortable: they simply have to be unwanted. Pandas live precarious lives on a diet of one species of bamboo. Snow leopards live on impossibly steep and barren slopes in the Himalayas and an unreliable diet of antelopes.

The migrants are not necessarily driven by competition, as suggested by Darwinian theory, but by their own ingenuity. The notion of giraffes developing longer and longer necks while a mad herd grazes all around them has always confounded me. I think that a giraffe becomes a giraffe by learning a new trick, isolating himself and others of his kind in a new niche, and reproducing, unbothered by competitors or predators for many generations. Many species observed on the discovery of islands have been as improbable in appearance and innocent of predation or competition.

Human immigrants, by this notion of competition and predation, move to their new countries because they cannot compete for jobs, or they are being persecuted. Though this is no doubt true for some immigrants. I think we can get a clearer picture of most immigrants’ ambitions by their wishes for their children rather than for themselves. They do not merely want their children to get jobs. They work so that their children will achieve a level of self-realization that they themselves never dared even to dream about. This goes well beyond the trivial notions of competition and self-preservation.

On the other hand, consider the seal clubbers. These appear to be an isolated population of humans who have carefully and abundantly bred themselves for cruelty and idiocy. How can there possibly be any good in destroying their environment and making it a living hell for the seals with whom they share it? These humans reproduce beyond their means and prostitute themselves to the ship owners to whom they provide the seals. In short, they behave as a pack of mad dogs, without loyalty even to themselves: the ultimate in domestication. They reproduce, all right, but are they fit, in the Darwinian sense? Would it not be better for them to make fewer offspring and give birth to themselves?

Has no one else said that humans merely contribute to a great ongoing experiment, where as many of life’s possibilities are being tried and tested: our contributions being different but no better than those of a butterfly or tarantula. We do not stand at the apex of a pyramidal scheme but merely form a tenuous link in a great circle.

Our question to ourselves should be: given our specific talents, how can we promote the existence of other life forms and enhance and support their contributions? Arguably, our most laudable talents are:

- Our invention of time beyond our own lifetimes;

- Reading and writing;

- Manipulation of the natural world.

All of this is quite pointless if we life solely for our own pleasure and reproduction and then crash and burn as an index species. It is useless even if we learn to respect Nature in the abstract, as something to fear and leave alone. No. Nature must become as real as a chick or a grasshopper eating from our hands, if we are to survive. It is simply not in us to feel an ideal as fiercely as a kiss.

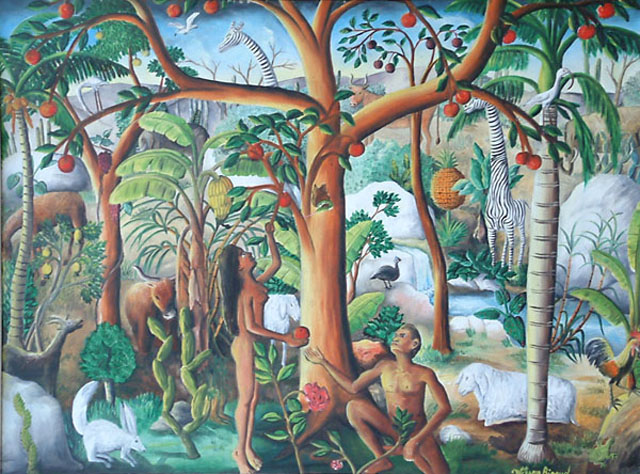

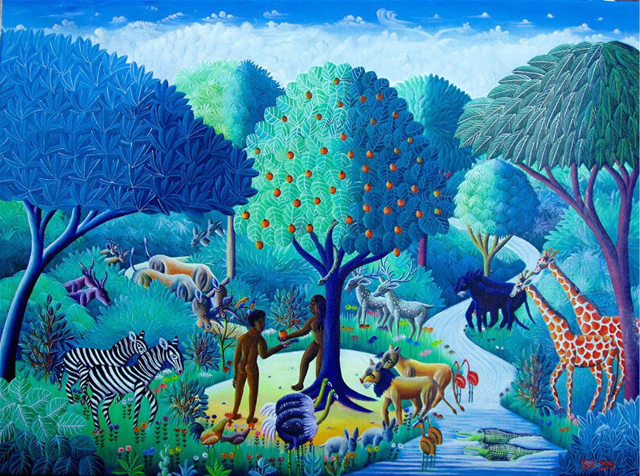

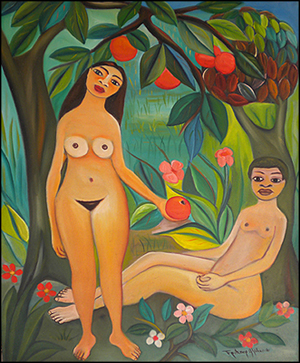

Dady Chery is a Haitian-born writer and the author of We Have Dared to be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation. Paintings are renditions of Paradise by Haitian artists Fritzner Alphonse, Wilson Bigaud, Gerard Fortune, Fritz Merise, and Pierre Maxo, respectively, from top to bottom.