Those Who Controlled the Past Should Not Control the Future

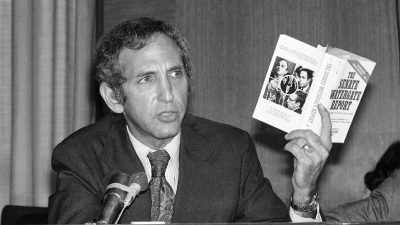

Daniel Ellsberg has a message that managers of the warfare state don’t want people to hear.

“If you have information that bears on deception or illegality in pursuing wrongful policies or an aggressive war,” he said in a statement released last week, “don’t wait to put that out and think about it, consider acting in a timely way at whatever cost to yourself…. Do what Katharine Gun did.”

If you don’t know what Katharine Gun did, chalk that up to the media power of the war system.

Ellsberg’s video statement went public as this month began, just before the 15th anniversary of when a British newspaper, the Observer, revealed a secret NSA memo — thanks to Katharine Gun. At the UK’s intelligence agency GCHQ, about 100 people received the same email memo from the National Security Agency on the last day of January 2003, seven weeks before the invasion of Iraq got underway. Only Katharine Gun, at great personal risk, decided to leak the document.

If more people had taken such risks in early 2003, the Iraq War might have been prevented. If more people were willing to take such risks in 2018, the current military slaughter in several nations, mainly funded by U.S. taxpayers, might be curtailed if not stopped. Blockage of information about past whistleblowing deprives the public of inspiring role models.

That’s the kind of reality George Orwell was referring to when he wrote:

“Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.”

Fifteen years ago,

“I find myself reading on my computer from the Observer the most extraordinary leak, or unauthorized disclosure, of classified information that I’d ever seen,” Ellsberg recalled, “and that definitely included and surpassed my own disclosure of top-secret information, a history of U.S. decision-making in Vietnam years earlier.”

The Pentagon Papers whistleblower instantly recognized that, in the Observer article,

“I was looking at something that was clearly classified much higher than top secret…. It was an operational cable having to do with how to conduct communications intelligence.”

What Ellsberg read in the newspaper story “was a cable from the NSA asking GCHQ to help in the intercepting of communications, and that implied both office and home communications, of every member of the Security Council of the UN. Now, why would NSA need GCHQ to do that? Because a condition of having the UN headquarters and the Security Council in the U.S. in New York was that the U.S. intelligence agencies promised or were required not to conduct intelligence on members of the UN. Well, of course they want that. So, they rely on their allies, the buddies, in the British to commit these criminal acts for them. And with this clearly I thought someone very high in access in Britain intelligence services must dissent from what was already clear the path to an illegal war.”

But actually, the leak didn’t come from “someone very high” in GCHQ. The whistleblower turned out to be a 28-year-old linguist and analyst at the agency, Katharine Gun, who had chosen to intervene against the march to war.

As Gun has recounted, she and other GCHQ employees “received an email from a senior official at the National Security Agency. It said the agency was ‘mounting a surge particularly directed at the UN Security Council members,’ and that it wanted ‘the whole gamut of information that could give U.S. policymakers an edge in obtaining results favorable to U.S. goals or to head off surprises.’”

In other words, the U.S. and British governments wanted to eavesdrop on key UN delegations and then manipulate or even blackmail them into voting for war.

Katharine Gun took action:

“I was furious when I read that email and leaked it. Soon afterwards, when the Observer ran a front-page story — ‘U.S. dirty tricks to win vote on Iraq war’ — I confessed to the leak and was arrested on suspicion of the breach of section 1 of the Official Secrets Act.”

The whistleblowing occurred in real time.

“This was not history,” as Ellsberg put it. “This was a current cable, I could see immediately from the date, and it was before the war had actually started against Iraq. And the clear purpose of it was to induce the support of the Security Council members to support a new UN resolution for the invasion of Iraq.”

The eavesdropping was aimed at gaining a second — and this time unequivocal — Security Council resolution in support of an invasion.

“British involvement in this would be illegal without a second resolution,” Ellsberg said. “How are they going to get that? Obviously essentially by blackmail and intimidation, by knowing the private wants and embarrassments, possible embarrassments, of people on the Security Council, or their aides, and so forth. The idea was, in effect, to coerce their vote.”

Katharine Gun foiled that plan. While scarcely reported in the U.S. media (despite cutting-edge news releases produced by my colleagues at the Institute for Public Accuracy beginning in early March of 2003), the revelations published by the Observer caused huge media coverage across much of the globe — and sparked outrage in several countries with seats on the Security Council.

“In the rest of the world there was great interest in the fact that American intelligence agencies were interfering with their policies of their representatives in the Security Council,” Ellsberg noted.

A result was that for some governments on the Security Council at the time, the leak “made it impossible for their representatives to support the U.S. wish to legitimize this clear case of aggression against Iraq. So, the U.S. had to give up its plan to get a supporting vote in the UN.” The U.S. and British governments “went ahead anyway, but without the legitimating precedent of an aggressive war that would have had, I think, many consequences later.”

Ellsberg said:

“What was most striking then and still to me about this disclosure was that the young woman who looked at this cable coming across her computer in GCHQ acted almost immediately on what she saw was the pursuit of an illegal war by illegal means…. I’ve often been asked, is there anything about the release of the Pentagon Papers on Vietnam that you regret. And my answer is yes, very much. I regret that I didn’t put out the top-secret documents available to me in the Pentagon in 1964, years before I actually gave them to the Senate and then to the newspapers. Years of war and years of bombing. It wasn’t that I was considering that all that time. I didn’t have a precedent to instruct me on that at that point. But in any case, I could have been much more effective in averting that war if I’d acted much sooner.”

Katharine Gun “was not dealing only with historical material,” Ellsberg emphasizes, she “was acting in a timely fashion very quickly on her right judgement that what she was being asked to participate in was wrong. I salute her. She’s my hero. I think she’s a model for other whistleblowers. And for a long time I’ve said to people in her position or my old position in the government: Don’t do what I did. Don’t wait till the bombs are falling or thousands more have died.”

By making her choice, Gun risked two years of imprisonment. In Ellsberg’s words, she seemed to be facing “a sure conviction — except that the government was not willing to have the legality of that war discussed in a courtroom, and in the end dropped the charges.”

As this month began, Katharine Gun spoke at a London news conference, co-sponsored by ExposeFacts and RootsAction.org (organizations I’m part of) and hosted by the National Union of Journalists. Speaking alongside her were three other whistleblowers — Thomas Drake, Matthew Hoh and Jesselyn Radack — who have emerged as eloquent American truth tellers from the NSA, State Department and Justice Department. The presentations by the four are stunning to watch.

Their initiatives, taken at great personal risk, underscore how we can seize the time to make use of opportunities for forthright actions of conscience. This truth is far from confined to what we call whistleblowing. It’s about possibilities in a world where silence is so often consent to what’s wrong, and disruption of injustice is imperative for creating a more humane future.

*

Licensed under Creative Commons.

Norman Solomon is the coordinator of the online activist group RootsAction.org and the executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. He is the author of a dozen books including “War Made Easy: How Presidents and Pundits Keep Spinning Us to Death.”