The “Thirdworldization” of the Russian Federation. IMF-World Bank Shock Treatment under Boris Yeltsin

Author’s Note

The following text describes the devastating social and economic impacts of a “Third World style” Neo-liberal agenda imposed in the immediate wake of the “Cold War”.

I was in Russia in 1992 undertaking field research as well as interviews for Le Monde diplomatique. What I witnessed was a process of engineered impoverishment and social devastation.

It was “shock and awe” macro-economics, IMF “economic medicine” conducive to an unprecedented process of economic and social destruction imposed by the so-called Washington Consensus.

There was no peaceful transition. America had Won the Cold War the objective of which was to dismantle the Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin was their faithful proxy President of the Russian Federation, acting on behalf of the Washington consensus.

The USSR collapsed in one fell swoop. It was a complex process of regime change, dismantling the Soviet Union, coupled with “shock and awe” macro-economic reforms.

The unspoken post-Cold war scheme was “economic warfare” which consisted in imposing a neocolonial agenda conducive to the dislocation and the demise of the national economies of the former republics of the Soviet Union.

It was regime change, an exceedingly complex process of economic and social dislocation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR),

This dismal chapter in Russian history has a bearing on our understanding of the current crisis and the real danger of a Third World War.

It should be understood by Western public opinion.

Michel Chossudovsky, Global Research, September 18, 2024

(emphasis added by the author, September 18, 2024, no modifications of the text)

.

Phase I: The January 1992 Shock Treatment

.

“In Russia we are living in a post-war situation. . .”, but there is no post-war reconstruction. “Communism” and the “Evil Empire” have been defeated, yet the Cold War, although officially over, has not quite reached its climax: the heart of the Russian economy is the military-industrial complex and “the G-7 wants to break our high tech industries. (. . .) The objective of the IMF economic program is to weaken us” and prevent the development of a rival capitalist power.[1]

The IMF-style “shock treatment”, initiated in January 1992, precluded from the outset a transition towards “national capitalism” – i.e. a national capitalist economy owned and controlled by a Russian entrepreneurial class and supported, as in other major capitalist nations, by the economic and social policies of the state. For the West, the enemy was not “socialism” but capitalism.

How to tame and subdue the polar bear, how to take over the talent, the science, the technology, how to buy out the human capital, how to acquire the intellectual property rights?

“If the West thinks that they can transform us into a cheap labor high technology export haven and pay our scientists US$ 40 a month, they are grossly mistaken, the people will rebel.”[2]

While narrowly promoting the interests of both Russia’s merchants and the business mafias, the “economic medicine” was killing the patient, destroying the national economy and pushing the system of state enterprises into bankruptcy.

Through the deliberate manipulation of market forces, the reforms had defined which sectors of economic activity would be allowed to survive. Official figures pointed to a decline of 27 percent in industrial production during the first year of the reforms; the actual collapse of the Russian economy in 1992 was estimated by some economists to be of the order of 50 percent.[3]

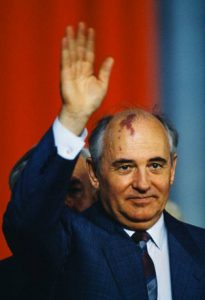

Image: Boris Yeltsin (Licensed under Creative Commons)

The IMF-Yeltsin reforms constitute an instrument of “Thirdworldization“; they are a carbon copy of the structural adjustment program imposed on debtor countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.

Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs, advisor to the Russian government, had applied in Russia the same “macro-economic surgery” as in Bolivia where he was economic advisor to the MNR government in 1985.

The IMF-World Bank program, adopted in the name of democracy, constitutes a coherent program of impoverishment of large sectors of the population. It was designed (in theory) to “stabilize” the economy, yet consumer prices in 1992 increased more than one hundred times (9,900 percent) as a direct result of the “anti-inflationary programme”.[4]

As in Third World “stabilization programs”, the inflationary process was largely engineered through the “dollarization” of domestic prices and the collapse of the national currency. The price liberalization program did not, however, resolve (as proposed by the IMF) the distorted structure of relative prices which existed under the Soviet system.

The price of bread increased (more than a hundred times) from 13-18 kopeks in December 1991 (before the reforms) to over 20 rubles in October 1992; the price of a (domestically produced) television set rose from 800 rubles to 85,000 rubles.

Wages, in contrast, increased approximately ten times – i.e. real earnings had declined by more than 80 percent and billions of rubles of life-long savings had been wiped out.

Ordinary Russians were very bitter: “the government has stolen our money”.[5]

According to an IMF official [whom I interviewed in Moscow], it was necessary to “sop up excess liquidity, purchasing power was too high”.[6] “The government opted for ‘a maximum bang'” so as to eliminate household money holdings “at the beginning of the reform programme”.[7]

According to one World Bank advisor, these savings “were not real, they were only a perception because [under the Soviet system] they [the people] were not allowed to buy anything”.[8] An economist of the Russian Academy of Science saw things differently:

Under the Communist system, our standard of living was never very high. But everybody was employed and basic human needs and essential social services although second-rate by Western standards, were free and available. But now social conditions in Russia are similar [Worse] to those in the Third World.[9]

Average earnings were below US$ 10 a month (1992-3), the minimum wage (1992) was of the order of US$ 3 a month, a university professor earned US$ 8, an office worker US$ 7, a qualified nurse in an urban clinic earned US$ 6.[10] With the prices of many consumer goods moving rapidly up to world-market levels, these ruble salaries were barely sufficient to buy food. A winter coat could be purchased for US$ 60 – the equivalent of nine months pay.”[11]

The collapse in the standard of living, engineered as a result of macro-economic policy, is without precedent in Russian history:

“We had more to eat during the Second World War”.

Under IMF-World Bank guidelines, social programs are to become self-financing: schools, hospitals and kindergartens (not to mention state-supported programs in sports, culture and the arts) were instructed to generate their own sources of revenue through the exaction of user fees.[12] Charges for surgery in hospitals were equivalent to two to six months earnings which only the “nouveaux riches” could afford. Not only hospitals, but theatres and museums were driven into bankruptcy. The famous Taganka Theatre was dismantled in 1992; many small theatres no longer had the funds to pay their actors. The reforms were conducive to the collapse of the welfare state. Many of the achievements of the Soviet system in health, education, culture and the arts (broadly acknowledged by Western scholars) have been undone.[13]

Continuity with the ancien regime was nonetheless maintained. Under the masque of liberal democracy, the totalitarian state remained unscathed: a careful blend of Stalinism and the “free” market. From one day to the next, Yeltsin and his cronies had become fervent partisans of neoliberalism.

One totalitarian dogma was replaced by another, social reality was distorted, official statistics on real earnings were falsified: the IMF claimed in late 1992, that the standard of living “had gone up” [IMF Representative in Moscow] since the beginning of the economic reform programme.[14] The Russian Ministry of Economy maintained that “wages were growing faster than prices”.[15] In 1992, the consumer price index computed with the technical support of the IMF, pointed to a 15.6 times increase in prices (1,660 percent).[16]

“But the people are not stupid, we simply do not believe them [the government]; we know that prices have gone up one hundred times”.[17]

The Legacy of Perestroika

During the period of perestroika, buying at state-regulated prices and reselling in the free market, combined with graft and corruption were the principal sources of wealth formation. These “shadow dealings” by former bureaucrats and party members became legalized in May 1988 with the Law on Cooperatives implemented under Mikhail Gorbachev.[18] This law allowed for the formation of private commercial enterprises and joint-stock companies which operated alongside the system of state enterprises. In many instances, these “cooperatives” were set up as private ventures by the managers of state enterprises. The latter would sell (at official prices) the output produced by their state enterprise to their privately owned “cooperatives” (i.e. to themselves) and then re-sell on the free market at a very large profit. In 1989, the “cooperatives” were allowed to create their own commercial banks, and undertake foreign-trade transactions. By retaining a dual price system, the 1987-89 enterprise reforms, rather than encouraging bona fide capitalist entrepreneurship, supported personal enrichment, corruption and the development of a bogus “bazaar bourgeoisie”.

Developing a Bazaar Bourgeoisie

In the former Soviet Union, “the secret of primitive accumulation” is based on the principle of “quick money”: stealing from the state and buying at one price and re-selling at another. The birth of Russia’s new “biznes-many”, an offshoot of the Communist nomenclature of the Brezhnev period, lies in the development of “apparatchik capitalism”. “Adam bit the apple and original sin fell upon ‘socialism'”.[19]

Not surprisingly, the IMF program had acquired unconditional political backing by the “Democrats”- i.e. the IMF reforms supported the narrow interests of this new merchant class. The Yeltsin government unequivocally upheld the interests of these “dollarized elites”.

Price liberalization and the collapse of the ruble under IMF guidance advanced the enrichment of a small segment of the population. The dollar was handled on the Interbank currency auction; it was also freely transacted in street kiosks across the former Soviet Union. The reforms have meant that the ruble is no longer considered a safe “store of value” – i.e. the plunge of the national currency was further exacerbated because ordinary citizens preferred to hold their household savings in dollars: “people are willing to buy dollars at any price”.[20]

Distorting Social Relations

The Cold War was a war without physical destruction. In its cruel aftermath, the instruments of macro-economic policy perform a decisive role in dismantling the economy of a defeated nation.

The reforms are not intent (as claimed by the West) in building market capitalism and Western style socio-democracy, but in neutralizing a former enemy and forestalling the development of Russia as a major capitalist power.

Also of significance is the extent to which the economic measures have contributed to destroying civil society and distorting fundamental social relations: the criminalization of economic activity, the looting of state property, money laundering and capital flight are bolstered by the reforms. In turn, the privatization program (through the public auction of state enterprises) also favored the transfer of a significant portion of state property to organized crime. The latter permeates the state apparatus and constitutes a powerful lobby broadly supportive of Yeltsin’s macro-economic reforms. According to a recent estimate, half of Russia’s commercial banks were, by 1993, under the control of the local mafias, and half of the commercial real estate in central Moscow was in the hands of organized crime.[21]

Pillage of the Russian Economy

The collapse of the ruble was instrumental in the pillage of Russia’s natural resources: oil, non-ferrous metals and strategic raw materials could be bought by Russian merchants in rubles from a state factory and re-sold in hard currency to traders from the European Community at ten times the price. Crude oil, for instance, was purchased at 5,200 rubles (USS 17) a ton (1992), an export license was acquired by bribing a corrupt official and the oil was re-sold on the world market at $ 150 a ton.[22] The profits of this transaction were deposited in offshore bank accounts or channeled towards luxury consumption (imports). Although officially illegal, capital flight and money laundering were facilitated by the deregulation of the foreign exchange market and the reforms of the banking system. Capital flight was estimated to be running at over $ 1 billion a month during the first phase of the IMF reforms (1992).[23] There is evidence that prominent members of the political establishment had been transferring large amounts of money overseas.

Undermining Russian Capitalism

What role will “capitalist Russia” perform in the international division of labor during a period of global economic crisis? What will be the fate of Russian industry in a depressed global market? With plant closures in Europe and North America, “is there room for Russian capitalism” on the world market?

Macro-economic policy under IMF guidance shapes Russia’s relationship to the global economy. The reforms tend to support the free and unregulated export of primary goods including oil, strategic metals and food staples, while consumer goods including luxury cars, durables and processed food are freely imported for a small privileged market but there is no protection of domestic industry, nor are there any measures to rehabilitate the industrial sector or to transform domestic raw materials. Credit for the purchase of equipment is frozen, the deregulation of input prices (including oil, energy and freight prices) is pushing Russian industry into bankruptcy.

Moreover, the collapse in the standard of living has backlashed on industry and agriculture – i.e. the dramatic increase in poverty does not favor the growth of the internal market. Ironically, from “an economy of shortage” under the Soviet system (marked by long queues), consumer demand has been compressed to such an extent that the population can barely afford to buy food.

In contrast, the enrichment of a small segment of the population has encouraged a dynamic market for luxury goods including long queues in front of the dollar stores in Moscow’s fashionable Kuznetsky area. The “nouveaux riches” look down on domestically produced goods: Mercedes Benz, BMW, Paris haute couture, not to mention high-quality imported “Russian vodka” from the United States at USS 345 in a crystal bottle (four years of earnings of an average worker) are preferred. This “dynamic demand” by the upper-income groups is, therefore, largely diverted into consumer imports financed through the pillage of Russia’s primary resources.

Acquiring State Property “at a Good Price”

The enormous profits accruing to the new commercial elites are also recycled into buying state property “at a good price” (or buying it from the managers and workers once it has gone through the government’s privatization scheme). Because the recorded book-value of state property (denominated in current rubles) was kept artificially low (and because the ruble was so cheap), state assets could be acquired for practically nothing.[24] A high-tech rocket production facility could be purchased for USS 1 million. A downtown Moscow hotel could be acquired for less than the price of a Paris apartment. In October 1992, the Moscow city government put a large number of apartments on auction; bids were to start at three rubles.

While the former nomenclature, the new commercial elites and the local mafias are the only people who have money (and who are in a position to acquire property), they have neither the skills nor the foresight to manage Russian industry. It is unlikely that they will play a strong and decisive role in rebuilding Russia’s economy. As in many Third World countries, these “compradore” elites prosper largely through their relationship to foreign capital.

Moreover, the economic reforms favor the displacement of national producers (whether state or private) and the taking over of large sectors of the national economy by foreign capital through the formation of joint ventures. Marlboro and Philip Morris, the American tobacco giants, for instance, have already acquired control over state production facilities for sale in the domestic market; British Airways has gained access to domestic air-routes through Air Russia, a joint venture with Aeroflot.

Important sectors of light industry are being closed down and replaced by imports whereas the more profitable sectors of the Russian economy (including the high-tech enterprises of the military-industrial complex) are being taken over by joint ventures. Foreign capital, however, has adopted a wait-and-see attitude. The political situation is uncertain, the risks are great: “we need guarantees regarding the ownership of land, and the repatriation of profits in hard currency”.[25] Many foreign enterprises prefer to enter “through the back door” with small investments. These often involve joint ventures or the purchase of domestic enterprises at a very low cost, largely to secure control over (highly qualified) cheap labor and factory space.

Weakening Russia’s High-Tech Economy

Export processing is being developed in the high-tech areas. It constitutes a very lucrative business: Lockheed Missile and Space Corporation, Boeing and Rockwell International among others have their eye on the aerospace and aircraft industries. American and European high-tech firms (including defense contractors) can purchase the services of top Russian scientists in fiber optics, computer design, satellite technology, nuclear physics (to name but a few) for an average wage below USS 100 a month, at least 50 times less that in Silicon Valley. There are 1.5 million scientists and engineers in the former Soviet Union representing a sizeable reserve of “cheap human capital”.[26]

Macro-economic policy supports the interests of Western high-tech firms and military contractors because it weakens the former Soviet aero- space and high-tech industries and blocks Russia (as a capitalist power in its own right) from competing on the world market. The talent and scientific know-how can be bought up and the production facilities can either be taken over or closed down.

A large share of the military-industrial complex is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defense. Carried out under its auspices, the various “conversion programs” negotiated with NATO and Western defense ministries aim at dismantling that complex, including its civilian arm, and preventing Russia from becoming a potential rival in the world market. The conversion schemes purport physically to demobilize Russia’s productive capabilities in the military, avionics and high-tech areas while facilitating the take-over and control by Western capital of Russia’s knowledge base (intellectual property rights) and human capital, including her scientists, engineers and research institutes. AT&T Bell Laboratories, for instance, has acquired through a “joint venture” the services of an entire research laboratory at the General Physics Institute in Moscow. McDonnell Douglas has signed a similar agreement with the Mechanical Research Institute.[27]

Under one particular conversion formula, military hardware and industrial assets were “transformed” into scrap metal which was sold on the world commodity market. The proceeds of these sales were then deposited into a fund (under the Ministry of Defense) which could be used for the imports of capital goods, the payment of debt-servicing obligations or investment in the privatization programs.

Taking Over Russia’s Banking System

Since the 1992 reforms and the collapse of many state banks, some 2,000 commercial banks have sprung up in the former Soviet Union of which 500 are located in Moscow. With the breakdown of industry, only the strongest banks and those with ties to international banks will survive. This situation favors the penetration of the Russian banking system by foreign commercial banks and joint-venture banks.

Undermining the Ruble Zone

The IMF program was also intent on abolishing the ruble zone and under- mining trade between the former republics. The latter were encouraged from the outset to establish their own currencies and central banks with technical assistance provided by the IMF. This process supported “economic Balkanization”: with the collapse of the ruble zone, regional economic power serving the narrow interests of local tycoons and bureaucrats unfolded.

Bitter financial and trade disputes between Russia and the Ukraine have developed. Whereas trade is liberalized with the outside world, new “internal boundaries” were installed, impeding the movement of goods and people within the Commonwealth of Independent States.[28]

.

Phase II: The IMF Reforms Enter an Impasse

.

Image: Yegor Gaidar (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

The IMF-sponsored reforms (under Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar) entered an impasse in late 1992.

Opposition had built up in parliament as well as in the Central Bank. The IMF conceded that if the government were to meet the target for the fiscal deficit, up to 40 percent of industrial plants might have been forced to close down. The president of the Central Bank, Mr. Gerashchenko with support from Arcady Volsky of the Civic Union Party, took the decision (against the advice of the IMF) to expand credit to the state enterprises, while at the same time cutting drastically expenditures in health, education and old-age pensions. The Civic Union had put forth an “alternative program” in September 1992. Despite the subsequent replacement of Yegor Gaidar as prime minister in the parliamentary crisis of December 1992, the Civic Union’s program was never carried out.

The IMF had, nonetheless, agreed in late 1992 to the possibility of “the less orthodox” approach of the centrist Civic Union prior to Gaidar’s dismissal. In the words of the IMF resident representative in Moscow: “the IMF is not married to Gaidar, he has a similar economic approach but we will work with his successor”.

At the beginning of 1993, the relationship between the government and the parliament evolved towards open confrontation.

Legislative control over the government’s budgetary and monetary policy served to undermine the “smooth execution” of the IMF program. The parliament had passed legislation which slowed down the privatization of state industry, placed restrictions on foreign banks and limited the government’s ability to slash subsidies and social expenditures as required by the IMF.[29]

Opposition to the reforms had largely emanated from within the ruling political elites, from the moderate centrist faction (which included former Yeltsin collaborators). While representing a minority within the parliament, the Civic Union (also involving the union of industrialists led by Arcady Volsky) favored the development of national capitalism while maintaining a strong role for the central state. The main political actors in Yeltsin’s confrontation with the parliament (e.g. Alexander Rutskoi and Ruslan Khasbulatov), therefore, cannot be categorized as “Communist hard-liners”.

The government was incapable of completely bypassing the legislature. Both houses of parliament were suspended by presidential decree on 21 September 1993.

Abolishing the Parliament in the Name of “Governance”

On 23 September, two days later, Mr. Michel Camdessus, the IMF managing director, hinted that the second tranche of a USS 3 billion loan under the IMF’s systemic transformation facility (STF) would not be forthcoming because “Russia had failed to meet its commitments” largely as a result of parliamentary encroachment. (The STF loan is similar in form to the struc- tural adjustment loans negotiated with indebted Third World countries). (See Chapter 3.)

President Clinton had stated at the Vancouver Summit in April 1993 that Western “aid” was tied to the implementation of “democratic reform”. The conditions set by the IMF and the Western creditors, however, could only be met by suspending parliament altogether (a not unusual practice in many indebted Third World countries). The storming of the White House [Russian: Белый дом, The House of the Government of the Russian Federation] by elite troops and mortar artillery was thus largely intent on neutralizing political dissent from within the ranks of the nomenclature both in Moscow and the regions, and getting rid of individuals opposing IMF-style reform.

The G7 had endorsed President Yeltsin’s decree abolishing both houses of parliament prior to its formal enactment and their embassies in Moscow had been briefed ahead of time. The presidential decree of 21 September was immediately followed by a wave of decrees designed to speed up the pace of economic reform and meet the conditionalities contained in the IMF loan agreement signed by the Russian government in May: credit was immediately tightened and interest rates raised, measures were adopted to increase the pace of privatization and trade liberalization.

In the words of Minister of Finance Mr. Boris Fyodorov, now freed from parliamentary control: “we can bring in any budget that we like.”[30]

Image: Boris Fyodorov (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

The timing of President Yeltsin’s decree was well chosen: Yeltsin’s finance minister Boris Fyodorov was scheduled to report to the G7 meeting of finance ministers on 25 September, the foreign minister Mr. Andrei Kosyrev was in Washington meeting President Clinton, the IMF-World Bank annual meeting was scheduled to commence in Washington on the 28 September, and 1 October had been set as a deadline for a decision on the IMF’s standby loan prior to the holding in Frankfurt of the meeting of the London Club of commercial bank creditors (chaired by the Deutsche Bank) on 8 October. And on 12 October, President Yeltsin was to travel to Japan to initiate negotiations on the fate of four Kuril islands in exchange for debt relief and Japanese “aid”.

Following the suspension of parliament, the G7 expressed “their very strong hope that the latest developments will help Russia achieve a decisive breakthrough on the path of market reforms.”[31] The German minister of finance Mr. Theo Wagel said that “Russian leaders must make it clear that economic reforms would continue or they would lose international financial aid”. Mr. Michel Camdessus expressed hope that political developments in Russia would contribute to “stepping up the process of economic reform”.

Yet despite Western encouragement, the IMF was not yet prepared to grant Russia the “green light”: Mr. Viktor Gerashchenko, the pro-Civic Union president of the Central Bank, was still formally in control of monetary policy; an IMF mission which traveled to Moscow in late September 1993 (during the heat of the parliamentary revolt), had advised Michel Camdessus that “plans already announced by the government for subsidy cuts and controls over credit were insufficient”.[32]

The impact of the September 1993 economic decrees was almost immediate: the decision to further liberalize energy prices and to increase interest rates served the objective of rapidly pushing large sectors of Russian industry into bankruptcy. With the deregulation of Roskhlebprodukt, the state bread distribution company, in mid-October 1993, bread prices increased overnight by three to four times.[33] It is worth emphasizing that this “second wave” of impoverishment of the Russian people was occurring in the aftermath of an estimated 86 percent decline in real purchasing power in 1992![34] Since all subsidies were financed out of the state budget, the money saved could be redirected (as instructed by the IMF) towards the servicing of Russia’s external debt.

The reform of the fiscal system, proposed by Finance Minister Boris Fyodorov in the aftermath of the September 1993 coup, followed the World Bank formula imposed on indebted Third World countries. It required “fiscal autonomy” for the republics and local governments by cutting the flow of revenue from Moscow to the regions and diverting the central state’s finan- cial resources towards the reimbursement of the creditors. The consequences of these reforms were fiscal collapse, economic and political Balkanization, and enhanced control of Western and Japanese capital over the economies of Russia’s regions.

“Western Aid” to Boris Yeltsin

By 1993, the reforms had led to the massive plunder of Russia’s wealth resulting in a significant outflow of real resources: the balance of payments deficit for 1993 was of the order of USS 40 billion -approximately the amount of “aid” ($ 43 billion) pledged by the G7 at its Tokyo Summit in 1993. Yet most of this Western “aid” was fictitious: it was largely in the form of loans (rather than grant aid) which served the “useful” purpose of enlarging Russia’s external debt (of the order of $ 80 billion in 1993) and strengthening the grip of Western creditors over the Russian economy.

Russia was being handled by the creditors in much the same way as a Third World country: out of a total of USS 43.4 billion which had been pledged in 1993, less than $ 3 billion was actually disbursed. Moreover, the agreement reached with the Paris Club regarding the rescheduling of Russia’s official debt – while “generous” at first sight – in reality offered Moscow a very short breathing space.[35] Only the debt incurred during the Soviet era was to be rescheduled;[36] the massive debts incurred by the Yeltsin government (ironically largely as a result of the economic reforms) were excluded from these negotiations.

With regard to bilateral pledges, President Clinton offered a meager USS 1.6 billion at the Vancouver Summit in 1993; $ 970 million was in the form of credits – mainly for food purchases from US farmers; $ 630 million was arrears on Russian payments for US grain to be financed by tapping “The Food for Progress Program” of the US Department of Agriculture, thus putting Russia on the same footing as countries in sub-Saharan Africa in receipt of US food aid under PL 480. Similarly, the bulk of Japanese bilateral “aid” to Russia were funds earmarked for “insurance for Japanese companies” investing in Russia.[37]

Into the Strait-Jacket of Debt-Servicing

The elimination of parliamentary opposition in September 1993 resulted in an immediate shift in Moscow’s debt-negotiation strategy with the commercial banks. Again, the timing was of critical importance. No “write-off’ or “write-down” of Russia’s commercial debt was requested by the Russian negotiating team at the Frankfurt meetings of the London Club held in early October 1993, only four days after the storming of the White House. Under the proposed deal, the date of reckoning would be temporarily postponed; USS 24 out of USS 3 8 billion of commercial debt would be rescheduled. All the conditions of the London Club were accepted by Moscow’s negotiating team, with the exception of Russia’s refusal to waive its “sovereign immunity to legal action”. This waiver would have enabled the creditor banks to impound Russia’s state enterprises and confiscate physical assets if debt-servicing obligations were not met. For the commercial banks, this clause was by no means a formality: with the collapse of Russia’s economy, a balance of payments crisis, accumulated debt-servicing obligations due to the Paris Club, Russia was being pushed into a “technical moratorium” – i.e. a situation of de facto default.

The foreign creditors had also contemplated mechanisms for converting Russia’s foreign exchange reserves (at the Central Bank as well as dollar deposits in Russian commercial banks) into debt-servicing. They also had their eye on foreign exchange holdings held by Russians in off-shore bank accounts.

The IMF’s economic medicine was not only devised to enforce debt-servicing obligations, it was also intent on “enlarging the debt”. The reforms contributed to crippling the national economy thereby creating a greater dependency on external credit. In turn, debt default was paving the way towards a new critical phase in Moscow’s relationship to the creditors. In the image of a subservient and compliant Third World regime, the Russian state was caught in the strait-jacket of debt and structural adjustment: state expenditures were brutally slashed to release state funds to reimburse the creditors.

The Collapse of Civil Society

As the crisis deepened, the population became increasingly isolated and vulnerable. “Democracy” had been formally installed but the new political parties, divorced from the masses, were largely heeding the interests of merchants and bureaucrats.

The impact of the privatization program on employment was devastating: more than 50 percent of industrial plants had been driven into bankruptcy by 1993.[38] Moreover, entire cities in the Urals and Siberia belonging to the military-industrial complex and dependent on state credits and procurements were in the process of being closed down.

In 1994 (according to official figures), workers at some 33,000 indebted enterprises, including state industrial corporations and collective farms, were not receiving wages on a regular basis.[39]

The tendency was not solely towards continued impoverishment and massive unemployment. A much deeper fracturing of the fabric of Russian society was unfolding, including the destruction of its institutions and the possible break-up of the Russian Federation. G7 policy-makers should carefully assess the consequences of their actions in the interests of world peace. The global geopolitical and security risks are far-reaching; the continued adoption of the IMF economic package spells disaster for Russia and the West.

Click the share button below to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Get Your Free Copy of “Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War”!

Notes

[1] Interview with an economist of the Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, October 1992.

[2] Ibid.

[3] A 50 percent decline in relation to the average of the previous three years. Interviews with several economists of the Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, September 1992.

[4] Based on author’s compilation of price increases over the period December 1991-October 1992 of some 27 essential consumer goods including food, transportation, clothing and consumer durables.

[5] According to the government’s official statement to the Russian Parliament, wages increased 11 times from January to September 1992.

[6] Interview with the head of the IMF Resident Mission, Moscow, September 1992.

[7] See World Bank, Russian Economic Reform, Crossing the Threshold of Structural Reform, Washington DC, 1992, p. 18.

[8] Interview with a World Bank advisor, Moscow, October 1992.

[9] Interview with an economist of the Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, September 1992.

[10] Interview in a Moscow polyclinic, interviews with workers in different sectors of economic activity, Moscow and Rostow on the Don, September-October 1992. See also Jean-Jacques Marie, “Ecole et sante en ruines”, Le Monde diplomatique, June 1992, p. 13.

[11] The price and wage levels are those prevailing in September-October 1992. The exchange rate in September 1992 was of the order of 300 rubles to the dollar.

[12] For further details see Jean Jacques Marie, op. cit.

[13] There is a failure on the part of the Russian economic advisors to uncover the theoretical falsehoods of the IMF economic framework. There is no analysis on how the IMF policy package actually works, and little knowledge in the former Soviet Union of policy experiences in other countries, including sub- Saharan Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe.

[14] Interview with IMF official, Moscow, September 1992.

[15] See Delovoi Mir (Business World), No. 34, 6 September 1992, p. 14.

[16] During the first nine months of 1992.

[17] Interview with ordinary Russian citizens, Rostov on the Don, October 1992.

[18] See International Monetary Fund, World Bank, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, A Study of the Soviet Economy, Vol. 1, Paris, 1991, part II, chapter 2.

[19] Paraphrase of “Adam bit the apple and thereupon sin fell on the human race” in Karl Marx “On Primitive Accumulation”, Capital (book 1).

[20] See “Ruble Plunges to New Low”, Moscow Times, 2 October 1992, p. 1.

[21] See Paul Klebnikov, “Stalin’s Heirs”, Forbes, 27 September 1993, pp. 124-34. 22. The government is said to have issued export licenses in 1992 covering two times the recorded exports of crude petroleum.

[23] According to estimates of the Washington-based International Institute of Banking.

[24] It is estimated that with a purchase of USS 1,000 of state property (according to the book value of the enterprise), one acquires real assets of a value of $300,000.

[25] Interview with a Western commercial bank executive, Moscow, October 1992.

[26] See Tim Beardsley, “Selling to Survive”, Scientific American, February 1993, pp. 94-100.

[27] Ibid.

[28] With technical assistance from the World Bank, a uniform tariff on imports was designed for the Russian Federation.

[29] The Central Bank was under the jurisdiction of parliament. In early September 1993, an agreement was reached whereby the Central Bank would be respon- sible to both the government and the parliament.

[30] Quoted in Financial Times, 23 September 1993, p. 1.

[31] Ibid, p. 1.

[32] According to Financial Times, 5 October 1993.

[33] See Leyla Boulton, “Russia’s Breadwinners and Losers”, Financial Times, 13 October 1993, p. 3.

[34] Chris Doyle, The Distributional Consequences of Russia’s Transition, Discussion Paper no. 839, Center for Economic Policy Research, London, 1993. This estimate is consistent with the author’s evaluation of price move- ments of basic consumer goods over the period December 1991-October 1992. Official statistics (which are grossly manipulated) acknowledge a 56 percent collapse in purchasing power since mid-1991.

[35] The amount eligible for restructuring pertained to the official debt contracted prior to January 1991 (USS 17 billion). Two billion were due in 1993, 15 bil- lion were rescheduled over 10 years with a five-year grace period.

[36] Only debt incurred prior to the cut-off date (January 1991) was to be resched- uled; 15 out of $ 17 billion were rescheduled, $ 2 billion were due to the Paris Club in 1993.

[37] See The Wall Street Journal, New York, 12 October 1993, p. A17. See also Allan Saunderson, “Legal Wrangle Holds Up Russian Debt Deal”, The European, 14-17 October 1993, p. 38.

[38] The World Bank has recommended to the government to “fracturize”, large enterprises, that is to break them up into smaller entities.

[39] See Financial Times, 1 August 1994, p. 1.

Featured image is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

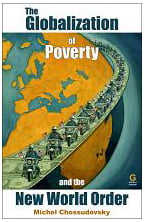

The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order

The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order

Author Name: Michel Chossudovsky

ISBN Number: 9780973714708

Year: 2003

Product Type: PDF File

Price: $9.50

In this new and expanded edition of Chossudovsky’s international best-seller, the author outlines the contours of a New World Order which feeds on human poverty and the destruction of the environment, generates social apartheid, encourages racism and ethnic strife and undermines the rights of women. The result as his detailed examples from all parts of the world show so convincingly, is a globalization of poverty.

This book is a skilful combination of lucid explanation and cogently argued critique of the fundamental directions in which our world is moving financially and economically.

In this new enlarged edition – which includes ten new chapters and a new introduction — the author reviews the causes and consequences of famine in Sub-Saharan Africa, the dramatic meltdown of financial markets, the demise of State social programs and the devastation resulting from corporate downsizing and trade liberalisation.