Thinking the Unthinkable: NATO’s Global Military Roadmap

Not content with expanding from 16 to 28 members over the past decade in a post-Cold War world in which it confronts no military threat from any source, state or non-state, and not sufficiently occupied with its first ground and first Asian war in Afghanistan, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization – the world’s only military bloc – is eager to take on a plethora of new international missions.

With the fragmentation of the Warsaw Pact and the breakup of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991 NATO, far from scaling back its military might in Europe, not to mention returning the favor and dissolving itself, saw the opportunity to expand throughout the continent and the world.

Beginning with the bombing campaign in Bosnia in 1995, Operation Deliberate Force and its 400 aircraft, and the deployment of 60,000 troops there under Operation Joint Endeavor, the Alliance has steadily and inexorably deployed its military east and south into the Balkans, Northeast Africa, the entire Mediterranean Sea, Central Africa, and South and Central Asia. It has also extended its tentacles into the South Caucasus, throughout Scandinavia including Finland and Sweden, and into the Asia-Pacific region where it has formed individual partnerships with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea along with recruiting troops from Mongolia and Singapore to serve under its command in the eight-year war in Afghanistan.

With the upgrading of its Mediterranean Dialogue program (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia), with the Persian Gulf component of the 2004 Istanbul Cooperation Initiative partnership underway and planned for the Gulf Cooperation Council states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and with the deployment of U.S.-trained Colombian counterinsurgency forces for its Afghan war, a military bloc ostensibly formed to protect the nations of the North Atlantic community now has armed forces and partnerships in all six inhabited continents.

It has waged war in Europe, against Yugoslavia in 1999, and in Asia, in Afghanistan (with intrusions into Pakistan) from 2001 to the present and into the indefinite future, and is currently conducting military operations off the coast of Africa in the Gulf of Aden. The “Soviet menace” invoked sixty years ago to create even at the time the world’s largest and most powerful military alliance receded into history a generation ago and the gap provided by the disappearance of the Warsaw Pact and the USSR has been filled by a military machine that can call upon two million troops and whose member states account for over 70 percent of world arms spending.

But the past fifteen years’ expansion is not sufficient for NATO’s worldwide ambitions. It is now in the process of elaborating a new Strategic Concept to replace that of 1999, introduced during the air war against Yugoslavia and the first absorption of nations in the former socialist bloc. One which NATO described at the time as the Alliance’s Approach to Security in the 21st Century. In the decade-long interim the bloc has come to refer to itself as 21st Century NATO, global NATO and expeditionary NATO. (The first Strategic Concept was formulated in 1991, the year of the breakup of the Soviet Union and the Operation Desert Storm war against Iraq.}

The updated version was deliberated upon at NATO’s sixtieth anniversary summit this April, the first held in two nations: Strasbourg in France and Kehl in Germany.

Over a year in advance the bloc’s Secretary General at the time, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, “called on the transatlantic military alliance to develop a new, long-term strategy designed to tackle third-millennium concerns such as cyber attacks, global warming, energy security and nuclear threats” and demanded that it increase its budget to address a “growing list of responsibilities.” [1]

If upon its founding in 1949 NATO justified the launching of a military bloc in a Europe still nursing the wounds of the deadliest and most destructive war in human history; if after the end of the Cold War it transformed its self-defined mission to encompass military intervention in the Balkans to prove its ability to enforce peace, however one-sided; if after September 21, 2001 it obediently adjusted to Washington’s agenda of a Global War On Terror and efforts against weapons of mass destruction everywhere but where they actually exist; in the past few years NATO has announced new roles and missions that will allow, in fact necessitate, its intrusion into any part of the globe for a near myriad of reasons.

If fact myriad is the exact word used on October 1 at a conference jointly organized by NATO and Lloyd’s of London – “the world’s leading insurance market” as it describes itself – by the latter’s chairman, Lord Peter Levene, in reference to NATO’s new “third millennium” Strategic Concept.

Levene’s address included these words: “Our sophisticated, industrialised and complex world is under attack from a myriad of determined and deadly threats. If we do not take action soon, we will find ourselves, like Gulliver, pinned to the ground and helpless, because we failed to stop a series of incremental changes while we still could.”

His allusion to the character who lends his name to Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels invites the opportunity of quoting a paragraph from it about the protagonist’s – and Levene’s – native land, Great Britain.

After Gulliver boasts to a foreign king of among other matters Britain’s vast colonial domains and its military prowess, his interlocutor responds:

“As for yourself, who have spent the greatest part of your life in travelling, I am well disposed to hope you may hitherto have escaped many vices of your country. But by what I have gathered from your own relation, and the answers I have with much pains wrung and extorted from you, I cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of little odious vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the surface of the earth.”

Lord Levene hosted the conference on the Alliance’s updated Strategic Concept, one which was attended by what were described as “200 high-level representatives from the security and business community.” [2]

This past July NATO announced that a “group of experts” would be convened to discuss and plan its new strategy. Former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, as much as anyone responsible for the Alliance’s first prolonged armed conflict, the 78-day air war against Yugoslavia, chairs the group. The co-chairman is Jeroen van der Veer, who until June 30 was chief executive officer of Royal Dutch Shell.

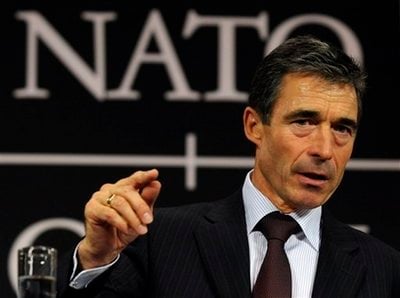

NATO’s Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen and Lord Levene co-authored a column in The Telegraph of October 1, so accommodating is the Western “free press,” to coincide with the conference of the same day.

They provided a litany of joint NATO-private business sector collaborations to protect the interests of the second party, Western-based transnational corporations, including but by no means limited to information technology, the melting of the polar ice cap, risk management for overseas investments and “storms and floods.”

The article states that “industry leaders, including those from Lloyd’s, have been involved in the current process to develop NATO’s new guiding charter, the Strategic Concept; indeed, the vice-chair of the group is the former chief executive of Shell, Jeroen van der Veer.” [3]

It also lays out far-reaching plans for military responses to a veritable host of non-military issues. “[G]overnments need to do some contingency planning…including focusing intelligence assessments on climate change, tasking military planners to incorporate it into their planning as well….They also need to step up their cyber-defences, as NATO has done in creating a deployable cyber-defence capability that can help its members if they come under attack.”

The last item is an allusion to events in Estonia in 2007, cyber attacks variously ascribed by Western government and NATO officials to Russian hackers or the Russian government itself. No proof has been offered for the accusations, though that hasn’t prevented major American elected officials from threatening the use of NATO’s Article 5 collective military force provision for use in similar cases.

That is precisely what Levene and Rasmussen meant by endorsing NATO’s “creating a deployable cyber-defence capability that can help its members if they come under attack.”

The urgency of the demand of Lord Levene of Portsoken and former Danish prime minister Rasmussen for history’s largest military bloc to protect Western commercial investments was expressed in an unadorned manner by the writers when they stated “Humans have always fought over resources and land. But now we are seeing those pressures on a bigger scale….

“We must be prepared to think the unthinkable. Lloyd’s developed its 360 Risk Insight programme and its Realistic Disaster Scenarios, and NATO its Multiple Futures project, precisely to lift our eyes from the present and scan the horizon for what might be looming.”

There will be no lack of opportunities for implementing what appears to be the heart of the new Strategic Concept.

Levene mentioned a thousand “determined and deadly threats” during his speech at the conference and Rasmussen started identifying them.

In his presentation at the conference the NATO chief framed his inventory of “deadly threats” by saying, “[T]he challenges we are looking at today cut across the divide between the public and private sectors….NATO, the EU and many Governments have had to send navies to try to defend against attacks. And it has cost insurance companies – many of which are part of the Lloyd’s market – millions.” [4]

The implication is inevitable that NATO and European Union warships are operating in among other locales the Horn of Africa so that firms like Lloyd’s will have to settle fewer claims.

Rasmussen’s speech included these pretexts for NATO interventions, these future casus belli, all in his own words:

Piracy

Cyber security/defense

Climate change

Extreme weather events – catastrophic storms and flooding

Sea levels will rise

Populations will move…in large numbers…always into where someone else lives, and sometimes across borders

Water shortages

Droughts

Food production is likely to drop

Arctic ice is retreating, for resources that had, until now, been covered under ice

Global warming

CO2 emissions

Reinforcing factories or energy stations or transmission lines or ports that might be at risk of storms or flooding

Energy, where diversity of supply is a security issue

Natural and humanitarian disasters

Big storms, or floods, or sudden movements of populations

Fuel efficiency, reduc[ing] our overall dependence on foreign sources of fuel

None of the seventeen developments mentioned can even remotely be construed as a military threat and certainly not one posed by recognized state actors.

Surely no “rogue states” or “outposts of tyranny” or “international terrorists” are responsible for climate change, yet Rasmussen’s proposals for contending with it are military ones.

“[T]he security implications of climate change need to be better integrated into national security and defence strategies – as the US has done with its Quadrennial Defence Review. That means asking our intelligence agencies to look at this as one of their main tasks. It means military planners should assess potential the impacts, update their plans accordingly and consider the capabilities they might need in future.”

He additionally advocated the inclusion of the over forty nations the 28-member bloc has individual and collective partnerships with in adding, “We might also consider adapting our Partnerships to take climate change into account as well. Right now, NATO engages in military training and capacity building with countries around the world. We focus on things like peacekeeping, language training and countering terrorism. What about also including cooperation that helps build capacity in the armed forces of our Partners to better manage big storms, or floods, or sudden movements of populations?” [5]

Rasmussen’s Pandora’s box of NATO concerns were for years adumbrated by his predecessor, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, who two years ago said that “[T]he subjects that the Alliance leaders are expected to discuss at the Bucharest Summit (Spring 2008) [are] NATO enlargement, missile defence, military capabilities, energy security, maritime situation awareness, cyber defence and other new security threats” [6] in one statement, and in another in the same period “emphasised the importance of such issues as enlargement, partnerships, energy security, the fight against global terrorism, energy security, cyber and missile defence which he expects to be discussed at the Bucharest summit.” [7]

In March of 2008 Scheffer was quoted in a news report titled “NATO Chief Calls for `Atlantic Charter’ to Define Strategy” as saying, “Challenges are multifaceted, interlinked and can arise from anywhere. We need to do a better job of scanning the strategic horizon. We can’t just be reactive….If NATO is to be capable to act anywhere in world, we will need more global partners.” [8]

During a visit to Israel this past January Scheffer expounded on the theme: “NATO has transformed to address the challenges of today and tomorrow. We have built partnerships around the globe from Japan to Australia to Pakistan and, of course, with the important countries of the Mediterranean and the Gulf. We have established political relations with the UN and the African Union that never existed until now. We’ve taken in new [countries], soon 28 in total, with more in line….[W]e are looking at playing new roles, as well, in energy security and cyber defence….” [9]

In a speech on March 22, “The Future of NATO,” he spoke of “long-term, costly and risky engagement far away from our own borders” and interventions “to cover a wider range of concerns and interests – from territorial defence, through regional stability, all the way to cyber defence, energy security, and the consequences of climate change.

“From just 12 member states we went to 26 – and soon 28. And from a purely ‘eurocentric’ Alliance NATO has evolved into a security provider that is engaged on several continents, working with a wide range of other nations and institutions.” [10]

His earlier reference to the African Union is to NATO’s deployment to the Darfur region of Sudan in 2005, its first African operation, and that to “political relations with the UN” to a backroom deal reached in September of 2008 between Scheffer and United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon that bypassed permanent Security Council members Russia and China.

Indeed, the growing list of excuses for NATO involvement and intervention, that of Scheffer and now of Rasmussen, is a dangerous arrogation of responsibility and functions that are properly those of the UN and not that of a non-elected military cabal whose combined member states’ populations are a small fraction of the human race.

NATO’s expansion and its progressively broader operations over the past ten years indicate in a glaring manner the Alliance’s intention to circumvent, subvert and jeopardize the very existence of the United Nations, a theme dealt with in a previous article, West Plots To Supplant United Nations With Global NATO. [11]

In addition to “guaranteeing energy security” by establishing military beachheads in the Balkans, Central and South Asia, the Caucasus, the Persian Gulf, the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of Guinea and retaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and participating in the American-led drive for a global missile shield, NATO has claimed for itself the exclusive mandate to address virtually all problems confronting humanity. In conjunction with Western arms manufacturers and the likes of Lloyd’s of London and Royal Dutch Shell.

1) Deutsche Presse-Agentur, March 16, 2008

2) NATO, October 1, 2009

3) The Telegraph, October 1, 2009

4) NATO, October 1, 2009]

5) Ibid

6) NATO, October 9, 2007

7) NATO, October 9, 2007

8)Bloomberg News, March 15, 2008

9) Haaretz, January 10, 2009

10) NATO, March 22, 2009

11) Stop NATO, May 27, 2009

http://rickrozoff.wordpress.com/2009/08/29/154