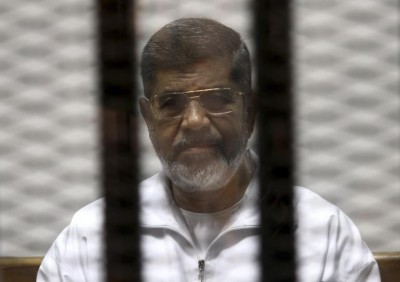

“They Decided to Kill Him”: Egyptian Officials Threatened Morsi Days Before Death

Deposed former president was told to disband Muslim Brotherhood or face consequences in secret talks with top officials, sources tell Middle East Eye

Mohamed Morsi and Muslim Brotherhood leaders in prison in Egypt were given an ultimatum by top officials to disband the organisation or face the consequences, Middle East Eye has learned.

They had until the end of Ramadan to decide. Morsi refused and within days he was dead.

Brotherhood members inside and outside Egypt now fear for the lives of Khairat el Shater, a former presidential candidate, and Mohammed Badie, the supreme guide of the Brotherhood, both of whom refused the offer.

The demand to Morsi and Brotherhood leaders to close the organisation down was first outlined in a strategy document written by senior officials around President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi which was compiled shortly after his re-election last year.

Middle East Eye has been briefed about its contents by multiple Egyptian opposition sources, one of whom had sight of it and who spoke about it on condition of anonymity.

The sources told MEE they were aware of the document and the secret negotiations with Morsi before his sudden death in prison last Monday.

‘Closing the file of the Muslim Brotherhood’

Some details of the protracted contacts between Egyptian officials and Morsi over the last few months have been withheld for fear of endangering the lives of prisoners.

Entitled “Closing the file of the Muslim Brotherhood”, the government document argued that the Brotherhood had been delivered a blow by the military coup in 2013, which was unprecedented in its history and bigger than the crackdowns the Islamist organisation faced under former presidents Nasser and Mubarak.

The document argued that the Brotherhood had been fatally weakened and there was now no clear chain of command.

It stated that the Brotherhood could no longer be considered a threat to the state of Egypt, and that the main problem now was the number of prisoners in jail.

The number of political prisoners from all opposition factions, secular and Islamist, is estimated to be about 60,000.

The government document envisaged closing the organisation down within three years.

It offered freedom to members of the Brotherhood who guaranteed to take no further part in politics or “dawa”, the preaching and social activities of the movement.

Those who refused would be threatened with yet further harsh sentences and prison for life. The document thought that 75 percent of the rank and file would accept.

If they agreed to close the movement down the leadership would be offered better prison conditions.

Pressure on Morsi

Huge pressure was applied on Morsi himself, who was held in solitary confinement in an annex of Tora Farm Prison, and kept away from lawyers, family or any contact with fellow prisoners.

“The Egyptian government wanted to keep this negotiation as secret as possible. They did not want Morsi to confer with colleagues,” one person with knowledge of events inside the prison said.

As negotiations dragged on, Egyptian officials became increasingly frustrated with Morsi, and the senior Brotherhood leadership in prison.

Morsi refused to talk about closing down the Brotherhood because he said he was not its leader, and the Brotherhood leaders refused to talk about national issues such as Morsi renouncing his title as president of Egypt and referred the officials back to him.

The deposed president refused to recognise the coup or surrender his legitimacy as elected president of Egypt. On the issue of ending the Brotherhood, he said he was the president of all Egypt and would not compromise.

“This continued for some time. Efforts were intensified in Ramadan. The regime became frustrated and they made it clear to other leaders that unless they persuaded him to give up and negotiate by the end of Ramadan, the regime would take other actions. They did not specify which,” sources with knowledge of the events told MEE.

For this reason, the sources who spoke to MEE believe Morsi was killed and that the other Brotherhood leaders who refused the demand to disband the organisation are now in mortal danger.

Morsi died aged 67 last Monday shortly after collapsing in court where he was facing a retrial on charges of espionage. Egyptian authorities and state media reported that he had suffered a heart attack.

But concerns that the conditions in which he was being held posed a threat to his health had been raised for years by his family and supporters, who said he had been denied adequate medical care for diabetes and a liver disease.

One Egyptian figure said:

“My analysis is that they decided to kill him at that particular time (the seventh anniversary of the second round of presidential elections). This explains the timing of his death. The main reason they decided to kill him was that they concluded he would never agree to their demands.”

The document was not the first offer that had been made to Brotherhood prisoners by Sisi’s government.

Before the 2018 document, there had been two offers made to them: release on condition of not engaging in politics for a specific time, and release on condition of not engaging in politics, but being allowed to continue with “dawa”, or the religious life of the community. Neither offer had been taken up.

Morsi’s death has sparked strong public criticism of his treatment. Ayman Nour, a former presidential candidate and political opponent, said Morsi had been “killed slowly over six years”.

“Sisi and his regime bear full responsibility for the outcome, and there is no other option but international arbitration into what he was subjected to, medical negligence and deprivation of all rights,” Nour, who now lives in exile, tweeted.

Secrets to share

In the final moments, Morsi urged a judge to let him share secrets which he had kept even from his lawyer, MEE reported.

Morsi said he needed to speak in a closed session to reveal the information – a request the deposed president had repeatedly appealed for in the past but never been granted.

Standing before the court, Morsi said he would keep the secrets to himself until he died or met God. He collapsed soon after.

Earlier in the same court session, fellow detainees Safwat al-Hejazi, an Islamist preacher, and Essam al-Haddad, who served as Morsi’s foreign affairs advisor, asked the judge to consider holding court sessions less frequently.

Haddad’s son Abdullah told MEE he fears his father and brother Gehad, who is also imprisoned, will share Morsi’s fate.

“There are many others who are on the verge of death and unless the international community speaks out and demands others to be released, many more will die, including my own father and brother,” he said.

MEE has contacted the Egyptian embassy in London to ask for comment on the document and the negotiations between the government and Morsi and senior Brotherhood officials in the months and weeks before his death.

The Egyptian foreign ministry last week condemned calls by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for an independent investigation into Morsi’s death.

A spokesperson for the foreign ministry said calls for an inquiry were a “deliberate attempt to politicise a case of natural death”.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.