The War over the Vietnam War

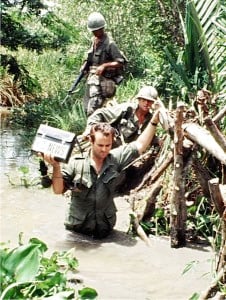

Image: ABC TV News cameraman Jim Dysilva at the Citadel in Hue at Tet 1968. (Photo credit: Don North)

Wars are fought twice, once on the battlefield and later in the remembering. In that way, the Vietnam War – though it ended on the battlefield four decades ago – continues as a battle of memory, history and truth. And the stakes are still high. Honest narratives about important past events can shape our destinies, helping to determine whether there will be more wars or maybe peace.

A few years ago, I was pleased to hear that the Pentagon would be funding a committee for the commemoration of the Vietnam War. I thought maybe, finally, we’ll get the record straight. But I didn’t have to read further than the keynote quote at the top of the new website to realize it was not to be.

Quoting President Richard Nixon, it read: “No event in history is more misunderstood than the Vietnam war. It was misreported then and is misunderstood now.”

I belong to the dwindling ranks of journalists who covered the war. We call ourselves “the Vietnam old hacks” and we got pretty exercised about this quote since it perpetuates the myth that the war would have worked out just fine if not for the discouraging words of some reporters. I wrote a letter to the chief of the commemoration committee, retired Lieutenant General Claude Kicklighter, protesting this slur on the thousands of journalists who tried to honestly cover the war, a slur coming from a U.S. president who was one of the most responsible for misleading the public about the war.

I badgered the committee for months but they were reluctant to take the quote down. I enlisted friends at the U.S. Army Center for History who strongly suggested to the committee that the quote was inappropriate. After six months through clenched teeth, they finally took it down. But many of the myths and falsehoods of the Vietnam War remain on the website.

So what went wrong in Vietnam? One of the prevailing and persistent myths is that the United States was betrayed by disloyal journalists. Even the U.S. Army commander in Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, subscribed to that old saw.

It doesn’t seem to matter how many times historians – even Army historians – challenge this myth, noting that the U.S. press on balance did a pretty good job covering a complex and dangerous conflict. The myth of the disloyal journalists who supposedly sabotaged what would have otherwise been an American victory just keeps coming back.

My Life in Vietnam

I landed in Vietnam in May of 1965, an eager and enterprising young reporter from Canada. I was like hundreds of other would-be-journalists going into the field to report the war as freelancers, arriving as this counter-insurgency conflict grew into a full-blown Asian war. And like so many of us I initially bought Washington’s rationale for the war – to save this little democracy from a Communist takeover and the start of falling dominoes in Asia.

The truth however didn’t take long to learn. At that time, the United States had the benefit of some brilliant journalists who took their craft seriously — and many were on the front lines of reporting about the gaps between the glowing PR and the grim reality.

For example, my late friend David Halberstam of the New York Times told me about an historic battle down in the Mekong Delta in late 1962 when the reality of the conflict was becoming evident. Hundreds of American helicopters had arrived in Vietnam promising great new technological advantages to defeat the Viet Cong.

On the first day of the battle, a few Viet Cong were killed. On the second day, an enormous helicopter assault was launched but nothing happened. On the third day, the same thing happened, no enemy, no battle.

On the way back to Saigon, Neil Sheehan, then with UPI, muttered about the waste of his time. Homer Bigart, an experienced World War II reporter for the New York Times, said, “What’s the matter Mister Sheehan?” Sheehan grumbled about three days spent tramping the paddy fields and no story to write.

“No story,” remarked Bigart, slightly surprised. “But there is a story. It doesn’t work. That’s your story, Mr. Sheehan. “

Indeed, the U.S. strategy in Vietnam didn’t work. It never worked. Not then, not ever. But the price for the folly was staggeringly high. The Vietnamese suffered some two million civilian dead, many killed by the heaviest aerial bombing in history.

In many ways, the young American soldiers, who were dropped into Vietnam, were victims, too, as they found themselves woefully ill-prepared for the rigors and cruelty of counter-insurgency warfare, often fought in villages packed with women and children. Some 58,000 U.S. soldiers died in the conflict and many more were scarred either physically or psychologically.

Nick Turse, who wrote Kill Anything that Moves, recently noted:

“Civilian suffering in Vietnam was the essence of a war caused by America’s callous use of power. I question whether the Henry Kissinger’s of today, Washington’s latest coterie of war managers, are any more willing to consider this than Kissinger was.”

Going Back

I have just returned from a three-week tour of Vietnam and Cambodia and found that there are those in Vietnam as well as in America who are still unwilling to hear honest voices about the war. Yet, returning to Vietnam for the fortieth anniversary of the war’s end with the Vietnam old hacks – we journalists who covered that lost war – was a moving experience and brought back many memories of the war years.

In a war full of surprises, there was no greater surprise for us than the Tet offensive attack on the U.S. Embassy on Jan. 31, 1968. Military analysts say one way to achieve decisive surprise in warfare is to do something truly stupid and the 15 Viet Cong sappers who carried out the daring embassy attack were poorly trained and unprepared, but its effects marked a turning point in the war and earned a curious entry in the annals of military history.

Today the imposing U.S. Embassy that withstood the attack has been torn down and replaced by a modest U.S. Consulate. A small marker stone in a garden, closed to the public, records the names of the seven American Marines and Military Police who died there. Outside the Consulate gates on the sidewalk is a brick monument engraved with names of Viet Cong sappers and agents who also died.

I couldn’t help imagining the scene if somehow U.S. Army PFC Bill Sebast and Viet Cong sapper Nguyen Van Sau, two soldiers who died on opposite sides of the Embassy wall, could return today to marvel at Saigon’s economic progress, with Vietnam and the U.S. having put aside old animosities to become valuable trading partners.

For the first time, the Vietnam Foreign Ministry treated us old hacks like people worth knowing, interested in our knowledge about the bloody war that we once covered. The truth is Vietnam is more concerned these days about its giant neighbor to the north, China, and even looks to the United States as a possible counterweight to China’s tendency to throw its significant weight around.

Judging the Journalists

So what about the recent Pentagon suggestion that we journalists “misreported the war?” Am I satisfied with my own coverage of the Vietnam war? No, I’m not. I think ignorance of Vietnam history and culture at first and the limitations of TV news sometimes made the truth suffer. A minute and a half was about max for an evening news report. Not nearly enough time to describe the complex events of the Vietnam War.

I also found my ABC News editors in New York reluctant to sound negative about the war. Critical stories got brutally edited or just mysteriously disappeared before air time.

The only censorship that I experienced was from my own news company. At the U.S. Embassy when the last Vietcong sapper was killed or captured, I quickly filmed a “standupper.” To conclude my report, I said, “Since the Lunar New Year, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese have proved they are capable of bold and impressive military moves that Americans never dreamed could be achieved. Whether they can sustain this onslaught for long remains to be seen.

“But whatever turn the war now takes, the capture of the U.S. Embassy here for seven hours is a psychological victory that will rally and inspire the Viet Cong. Don North ABC News Saigon.”

But my instant analysis never made it to the air on ABC News. I was accused of “editorializing” and the standupper was killed by some producer on the evening news. Ironically, however, the standupper with other out-takes ended up in the “ABC Simon Grinberg Library” where it was later found by producer Peter Davis and used in his Academy Award winning film, “Hearts and Minds.”

So it’s true that the truth about the Vietnam War often suffered, but not in the way Nixon’s quote suggested. Much of the U.S. media reporting put the war in too rosy – not too harsh – a light. More accurate journalism would have more consistently challenged what Neil Sheehan later called “A Bright Shining Lie,” the upbeat PR for a misguided war.

A US Marine pinned down by North Vietnamese Army sniper fire in the Citadel 1968 at Tet. (Photo credit: Don North)

And the lessons of Vietnam – fruitlessly discussed over the past half century – have taught Washington so little that today’s war hawks replicated many of the same Vietnam mistakes in Afghanistan and Iraq — the same hubris, the same over-reliance on technology and propaganda, the same ignorance of complicated foreign cultures.

So what were the real lessons learned about journalism in the Vietnam War? In spite of difficulties, censorship and the fog of war, I believe much of our Vietnam reporting was accurate and has withstood the scrutiny of time. However, has U.S. war reporting today improved any more than American foreign policies?

Mark Twain once wrote of what I think is a major dilemma of our age. He said, “If you don’t read the newspapers you are uninformed. If you do read the newspapers you are misinformed.”

The great reporter A.J. Liebling of the Baltimore Sun once observed, “The Press is the weak slat under the bed of democracy.”

Recently Bill Moyers while at PBS picked up on Liebling’s observations when he wrote:

“After the invasion of Iraq, the slat in the bed broke and some strange bedfellows fell to the floor … the establishment journalists, neo-con polemicists, beltway pundits, right-wing warmongers flying the skull and crossbones of the ‘balanced and fair brigade.’ And administration flaks whose classified leaks were manufactured lies … all romping on the same mattress in the foreplay to disaster. Thousands of casualties and billions of dollars later, most of the media co-conspirators caught in ‘flagrante delicto’ are still prominent, still celebrated, and still holding forth with no more contrition than a weathercaster who made the wrong prediction as to the next day’s temperature.”

And the same sort of “group think” and hostility to dissent that proved so disastrous in Vietnam a half century ago and Iraq a decade ago is ascendant again in Washington today.

The New York Times and Washington Post land on my doorstep every day and I’m appalled to read how “neocon ideology” appears to have seized control of the editorial pages, a development that should concern every American. Inevitably military power is recommended as a first, not a last resort.

Suggestions about seeing a conflict from the other side’s perspective is dismissed as soft-headed and un-American. Instead, it’s easier to talk tough and wave the flag, while squandering the nation’s tax dollars on military hardware and military adventures, even as millions of American families slip beneath the poverty line.

At West Point last May, President Obama observed,

“Some of our most costly mistakes come from, not our restraint, but from our willingness to rush into military adventures without thinking through the consequences. Just because we have the best hammer, does not mean that every problem is a nail.”

Don North is a veteran war correspondent who covered the Vietnam War and many other conflicts around the world. He is the author of a new book, Inappropriate Conduct, the story of a World War II correspondent whose career was crushed by the intrigue he uncovered.