The US Military Presence in Australia. The “Asia-Pacific Pivot” and “Global NATO”

Asymmetrical Alliance and its Alternatives

Through the ANZUS alliance, Australia, like Japan and South Korea, has been a key part of the United States “hub-and-spokes” Asia-Pacific alliance structure for more than sixty years, dating back to the earliest years of the Cold War and the conclusion of post-war peace with Japan.

An historical chameleon, the shape of the alliance has continually shifted – from its original purpose for the Menzies government as a US guarantee against post-war Japanese remilitarisation, to an imagined southern bastion of the Free World in the global division of the Cold War, on to a niche commitment in the Global War On Terror, to its current role in the imaginings of a faux containment revenant against rising China.

As one hinge in the Obama administration’s Pacific pivot, Australia is now more deeply embedded strategically and militarily into US global military planning, especially in Asia, than ever before. As in Japan and Korea, this involves Australia governments identifying Australian national interests with those of its American ally, the integration of Australian military forces organizationally and technologically with US forces, and a rapid and extensive expansion of an American military presence in Australia itself.

This alliance pattern of asymmetrical cooperation, especially in the context of US policy towards China, raises the urgent question of what alternative policy an Australian government concerned to maintain an autonomous path towards securing both its genuine national interests and the global human interest should be following.

The US Empire of Bases

The United States military is fond of talking about “lily pads” these days, referring to a network of new United States military bases around the world, but particularly in Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and Africa. It’s not all that new in fact, and it’s not all that small. Back in 2005 the US army logistics journal predicted that economics and political hostility would mean that the United States would not have permanent, large-scale military installations in another country. The U.S. Army, so the argument went, would use other countries’ existing facilities, with

“only a skeletal staff and an agreement with the host country that the base could be used as a forward operating base in a time of crisis. These ‘lily-pad’ bases would be austere training and deployment sites often in areas not previously used for U.S. bases.”2

In reality, of course, the United States has continued to maintain huge bases abroad, and has expanded its bases on its own colonial territories such as Guahan. But it is correct to say that the U.S. has a great many new, small, forward bases. The formal name for these small lightweight lily pad bases is Cooperative Security Locations, and the Pentagon’s Africa Command, for example, according to the Congressional Research Service in 2011 had

“access to locations in Algeria, Botswana, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Tunisia, Uganda, and Zambia.”3

These numbers have since been dwarfed by an extraordinarily rapid and extensive growth in the US military presence in Africa under the “small footprint” brand. In September 2013 Nick Turse documented a US presence in 49 of Africa’s 54 coutries, mostly in the form of Cooperative Security Locations.4 We should also add more or less unofficial Cooperative Security Locations in the form of bases for armed combat drones operated by the Central intelligence Agency or the military in the same part of the world – for example in Niger, Yemen, Ethiopia, and in the tiny island state of the Seychelles. These, together with US and coalition military bases in Afghanistan, some of them much larger than lily pads, make up the 60 or so US drone bases outside the United States.

Nick Turse: U.S. Military’s Pivot to Africa, 2012-2013, Source. |

The light footprint that the lily pad approach is looking for is partly a matter of economics – it’s much cheaper to piggyback off an allied country’s facilities – or, in some cases, a country that may be none too willing, but not in a position to say no. It’s also, as Turse rightly stresses, a sleight of hand: the illusion of a “small footprint” is also maintained by keeping the headquarters for AFRICOM out of sight in Germany.

The lily pads aside, America’s global network of bases numbers somewhere north of 1,000 worldwide.5 The imprecision is not a matter of exaggeration: it’s simply that there is no authoritative count, even with the assistance of the Pentagon’s annual Base Structure Report to Congress on the real estate side of things.6 According to the Base Structure Report in 2012, the Pentagon had 666 facilities outside the United States, plus another 94 in territories such as Guam.

However, that real estate count did not include a single base or facility in Afghanistan – where there are more than 400. And then there are the Cooperative Security Locations, CIA “secret” bases, and so on. Not unreasonably did the late Chalmers Johnson speak of America’s empire of bases.7

Why is the Pentagon thinking about lily pads? There are two main reasons. The first reason is simply financial – or more precisely, the combination of cost and extreme budgetary strain and Congressional deadlock. Maintaining all those military facilities at home and abroad is an extraordinarily expensive exercise. Costs have to be cut, or sources of revenue to support found.8 Make them smaller, lighten the footprint, share the burden. Better still, if possible, to get an ally to either contribute to the cost – as Japan does for example, in its massive “sympathy budget” contribution to the cost of US forces in Japan – or best of all, get the ally to provide the base access gratis, as Australia appears to be doing in many cases of US access to ADF facilities.

The bases and the Asia pivot

But the second reason is the dramatic shift in US strategic concerns under the Obama administration, concerned to rebalance US global power from the disasters of the Bush administration’s wars of choice in Iraq and Afghanistan – rebalancing around the “Asia pivot”.

This involves six elements of “a forward deployed diplomacy” to deal with “the rapid and dramatic shifts playing out across Asia”. As former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton put it:

“strengthening bilateral security alliances; deepening our working relationships with emerging powers, including with China; engaging with regional multilateral institutions; expanding trade and investment; forging a broad-based military presence; and advancing democracy and human rights.”9

The strategic core concerns the long-running ambivalence about China in US ruling circles, an ambivalence that derives from the complex cross-cutting interplay of political, military, economic, and financial impulses and tensions in an age of uneven globalization.

Is China to be the United States’ new global strategic partner in a positive sum global game as seemed to be preferred under the Clinton administration, and now, for example, in the substantial cooperative achievements of US – China cooperation on climate change under the Obama administration?

Or is it going to be conflict, as in the G.W. Bush administration’s early preference for a strategic competition, and now as in the Obama administration, with successive secretaries for defense articulating primitive theories of the “inevitability” of a rising power coming into conflict with a fading but not mortally wounded global hegemon?10

If you are in Beijing, which American spokesperson do you listen to? The one talking about cooperation between great powers, or the one building new military bases?

The resolution of this matter – the choice by both the United States and China for cooperation or conflict – is still by no means clear, with Obama pursuing close dialogue with China on rtain issues, such as climate change, but also invoking the US-Japan alliance over Japan’s dispute with China about the Diaoyutai/Senkakus – themselves the fruits of Japanese imperial plunder. US military strategy, with enthusiastic Australian and Japanese support, has increasingly emphasized a robust realignment of US and allied forces to the east and south of China and in the Indian Ocean, with the clarion call to “maintain control of sea lanes from the Middle East” – despite the fact that China is as dependent on those sea lanes as are Japan and South Korea.

In the non-military area, the United States is leading these same countries to form a trading bloc in the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a 12-country free trade bloc that would encompass 800 million people from Vietnam to Chile to Japan, but excluding China.11 China meanwhile is finalising negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with the ASEAN states, plus India, Japan, South Korea, and Australia and New Zealand, in a trading bloc that will include 3 billion people.12

The United States is clearly going far beyond mere hedging on its future options. The Chinese military see this as an attempt at containment, as in the Cold War containment of the Soviet Union. If containing China is the objective of at least some in the Obama administration, it is a strategic delusion in a world where the US and Chinese economies are bound together very tightly, and, so far, lacking a foundation of a sense of profound division, mistrust, and global opposition that characterised the Cold War.

But things are certainly changing. US hegemony in East and Southeast Asia – this is the system of power and rules built on the victory of 1945, nuclear alliances, and on the 1972 accord between Nixon and Mao for China to take the path of export-led industrialization into the US-controlled regime of world trade and globalised production platforms – has begun to dissolve as some allied elites in Japan and Korea become more nationalistic, question American political resolve and military capacity, and begin to see their interests as less fully aligned with the United States. And in China, Beijing is increasingly interested in challenging the US presumption that it writes the rules of global capitalism and regional security practices.

Let me just take one example of the latter. The United States is currently greatly concerned that Chinese military capacities are now such that it will be very difficult for the US navy aircraft carrier task forces to operate close to the Chinese coast – as it has been accustomed to do ever since 1945. The important question to ask is not whether the US navy is able to improve its military capacity to do so safely, but what the attitude of the United States would be to a Chinese carrier task force 200 kilometres off the Californian coast. Looking at the issue this way reminds us that the way we look at things tends to reflect the power of ideology and the ideology of ruling powers.

Whether the Obama “Asia pivot” can revitalise American hegemony in Asia – through global military reorganisation and modernization, strengthened bilateral alliances, new multilateral institutions like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and restructured political and economic relationships with former Cold War outliers like India and Vietnam – remains to be seen. But certainly security issues are now front and centre for the US relationship with China, with the shadow of a revivified containment policy not far off the stage.

Australia Between the United States and China

In all of this Australian policy is fraught. The Canberra mantra that Australia must not be forced to choose between its principal military ally and its largest trading partner focuses on a contradiction between 60 years of security ties to the US and the deep but asymmetrical trade interdependence with China – asymmetrical because while there are other potential quarries in the world, even Japan and Korea cannot constitute a replacement for China as an Australian resources customer.

Two sets of Australian strategic developments are relevant here. The first is the deepening integration of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) with the armed forces of the United States, Japan, and NATO – the latter two themselves the subject of ever closer integration with the United States. The 2007 Australia-Japan Security Cooperation Declaration and Australia’s formal partnership with NATO buttress the bilateral Australia-US developments defined through the annual Australia-United States ministerial talks (AUSMIN).

This integration is manifest organisationally, operationally and materially. The AUSMIN process has provided the institutional framework for bilateral working groups of officials and military focussing on the mantra of “interoperability” – with implications for organisational culture, standard operating procedures, weapons systems and logistics compatibility, and shared operational practises in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Taken together, the result of these policy and force structure changes may well be, from a Chinese perspective, that Australia is not so much hosting US military bases, but is becoming a virtual American base in its own right. That perspective may be overwrought, but almost a decade of continuous developments in joint Australia-US defence facilities and new levels of US access to Australian facilities undoubtedly change Australia’s strategic situation profoundly.13

|

One issue that needs close examination is the extent to which these still ongoing developments are the result of US pressure on its Australian ally, or rather Australian governments seeking to deepen the involvement of the US in the region and increase the perceived utility of Australia to the US by anticipating American needs, and taking the initiative by offering the facilities first.14 In explaining the build-up to the Darwin deployments, The Australian newspaper suggested, with some understatement, that “Australia might have been encouraging the US to increase its military presence”, citing the US Secretary of the Navy, Ray Mabus, conceding that “It’s fair to say that we will always take an interest in what the Australians are doing and want to do.”15

|

The US Military Presence in Australia: Asymmetrical Cooperation

Let me turn to the specifics of the US military presence in Australia. In recent years successive Australian governments have been insistent on the joint character of any cooperative activity within Australia with US military forces and intelligence agencies. For example, the ratification of the 2008 treaty concerning US access to the once again joint North West Cape facility confirmed that the treaty “includes a requirement that U.S. use of the Station be in accordance with the Australian Government’s policy of full knowledge and concurrence.”16

Another Australian government mantra, usually from the Defence Minister, has been that “There are no US bases in this country.” This is not correct. This is not just a politician being economical with the truth, but in fact a complete misrepresentation of strategic reality, which is in fact one of fundamental and inherent asymmetrical cooperation between the United States and Australia.

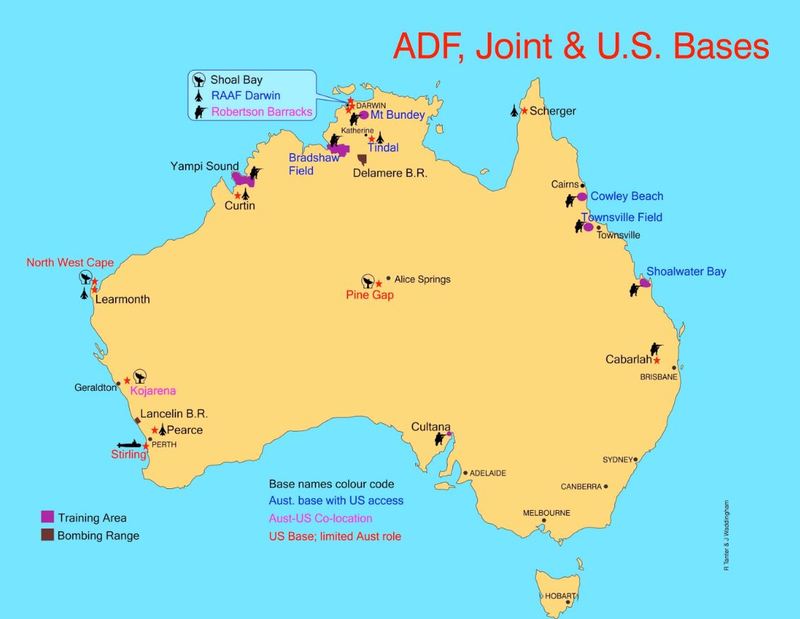

Of course, there are differences of degree as to which military and intelligence bases on Australian soil can be appropriately regarded as “joint facilities”. If you like, there are three degrees of “jointness”.

|

Firstly, there are ADF bases to which US military forces have access. Secondly, there are Australian bases co-located with American facilities. And thirdly, there are US bases to which Australia has at least limited access.

ADF bases with US access

Essentially, the US military has access to all major ADF training areas, northern Australian RAAF airfields, port facilities in Darwin and Fremantle, and highly likely future access to an expanded airfield on the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean. The actual level of access is variable, but will certainly increase with the full Darwin deployment of the Marine Air Ground Task Force and US Air force elements to nearby air bases, and with the planning for the US Navy access to the Stirling naval base in Perth now underway.

ADF/US military co-locations

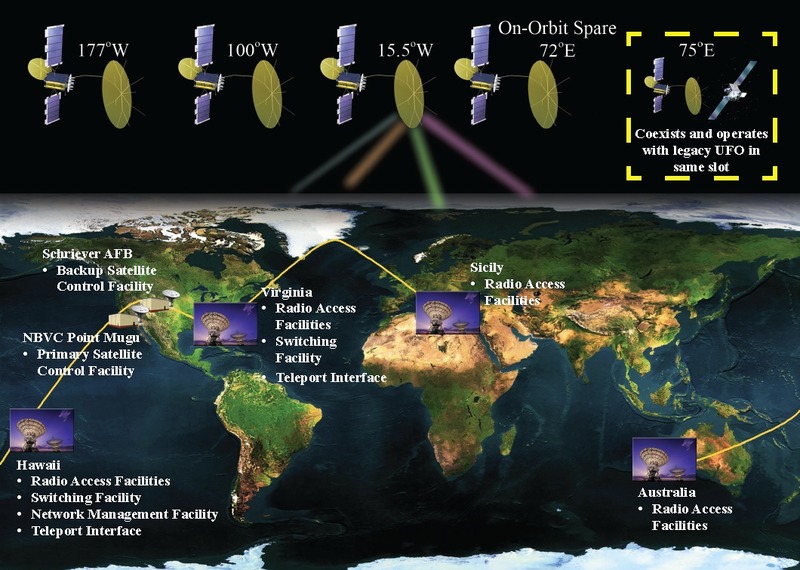

Two Australian bases have, or will shortly have, co-located US military facilities. Robertson Barracks in Darwin will house permanent US command, communications and logistics elements to service the full complement of 2,500 Marines on permanent rotation through the base planned for 2016. This will require considerable expansion of Robertson on top of its recent substantial expansion for ADF purposes. The two part physical expansion of the Australian Defence Satellite Communications Ground Station at Kojarena near Geraldton in West Australia for the US Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) facility and the shared Wideband Global SATCOM system (WGS) facility is another example.17

Just how functionally separated the US elements will be is not yet clear. In the case of Kojarena much will depend on whether, as seems likely, existing trends towards U.S.-Australian communications systems integration continue to deepen, and the degree to which security issues segregate ADF and US activities. And in the case of Darwin and Robertson Barracks, much will depend on the degree and types of cooperative and collaborative training and operations that the ADF and the MAGTF become involved in. But the Robertson Marine presence will be permanent, and will grow beyond the current nominal MAGTF target of 2,500 to what the Chief of Naval Operations said in July 2013 would be “an ARG MEU [Amphibious Ready Group, Marine Expeditionary Unit] –sized capability by the end of this decade”.18

American bases, with Australian access

The Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap and North West Cape Naval Communications Station are in fact best understood as US bases to which Australia has access, whatever the sign on the door may say. They were built by the United States, the core facilities were paid for and are maintained by the United States, and the facilities only function in concert with the huge American investment in military and intelligence satellite and communications systems. Take the last away, and nothing of significance is left.

Pine Gap is a United States intelligence and military facility to which Australia has a certain level of access. Whether this amounts to the government’s often proclaimed “full knowledge and concurrence” with the operations of these facilities is quite another matter.19

US Marines and Osprey, exercise Koolendong, Bradshaw Field Training Range, September 2013 |

Let me turn to the specifics of these bases. Important though they were, the Obama – Gillard announcements in Darwin in November 2011 – about the Marine and US Air Force deployments, and later, plans for HMAS Stirling and Cocos Islands – were just the tip of the iceberg. The importance of the Marine deployment is first and foremost symbolic and political, rather than strategic. Over the past decade there has been a continuous expansion of US access to a range of bases which, taken together, overshadow the highly visible but not militarily important deployment of 2,500 Marines on ‘permanent rotation’.

The Marine Air–Ground Task Force consists of command, ground combat and air combat elements available for rapid deployment for expeditionary combat. The ADF Robertson Barracks deployment will in time become an effectively permanent joint base, with the organisational heart of the Task Force, and possibly a larger Marine Expeditionary Unit.

The three main training locations for the MAGTF and the US Air Force are all located in the Northern Territory: the giant Bradshaw Field Training Area (almost the size of Cyprus, with 7,000 troops every dry season), the Mount Bundey Training Area, and the Delamere Air Weapons Range, 220 km south-west of Katherine. Together they make up the ADF’s North Australian Range Complex, most importantly now electronically networked to US Pacific Command in Hawaii.

The Australian Defence Satellite Communications Ground Station (ADSCGS) at Kojarena, 30 km east of Geraldton, is operated by Australia’s most important intelligence agency, the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD). Kojarena station is a powerful and large signals interception facility, part of a worldwide system of satellite communications monitoring organised under the most important defence agreement Australia has, the UKUSA Agreement between the US, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

Australian Defence Satellite Communications Ground Station, Kojarena. Google Earth, December 2012. MUOS and WGS ground terminals are located in the upper left arm of the facility |

Under two agreements signed in 2007, Kojarena has become closely integrated with US communications systems in two ways. One is partnership in the Wideband Global SATCOM system – Australia paid for one of seven or more satellites and gets access to them all. The other is a new separate Kojarena facility for the US military secure mobile phone system, known as MUOS.20

North West Cape

|

Great changes are taking place at the Harold E. Holt Naval Communications Station, a naval communications facility at North West Cape on the Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia built in the 1960s to communicate with US Polaris missile carrying submarines using very low frequency (VLF) transmissions. Over time, missile and submarine technology improved, US needs changed, and North West Cape was turned over to the Australian Navy in 1999. Now new US strategic concerns about the rise of China and Indian Ocean naval competition has brought the US back to the VLF facility.

Caption: VLF antennas at Harold E. Holt Naval Communications Station, North West Cape

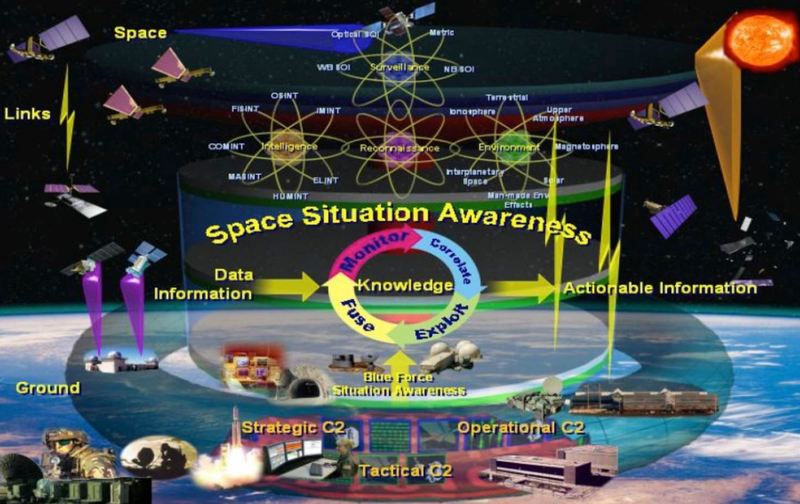

But a second new facility to be built at North West Cape is even more important, bringing Australia into the powerful pull of US determination to establish what it formally calls dominance in space. Under the Space Situational Awareness (SSA) Partnership the US intends to locate two powerful space surveillance sensors in Western Australia, one, a space radar at North West Cape, and the other a new and highly powerful space telescope either at North West Cape or Kojarena. Together they will monitor objects in space, small and large, in low earth orbit (in orbits out to 1,000 kms.) and geo-stationary orbit (at about 36,000 kms.)

VLF antennas at Harold E. Holt Naval Communications Station, North West Cape |

The Australian government stresses the space radar’s role for the global public good of monitoring ‘space junk’. What the Australian government did not say is that its more important role is for space warfare within US Strategic Command, in “mission payload assessment” – finding and monitoring non-US satellites in the event of war. The mission of Space Command is US dominance in space, and North West Cape is now to be part of that mission.

Building on the Space Situational Awareness (SSA) Partnership signed at AUSMIN 2010, a new agreement was signed in Perth at AUSMIN 2012 as “a demonstration of our commitment to closer space cooperation”. This authorized the transfer of a US C-band (4-8Ghz) mechanical radar space-tracking radar from Antigua in the West Indies (previously used for tracking space US launches from Cape Canaveral) to North West Cape.21

Source: Russell F. Teehan, Responsive Space Situation Awareness in 2020, Blue Horizons Paper, Center for Strategy and Technology, Air War College, April 2007 |

In Australia, under the auspices of the US Joint Space Operations Center, the space radar will be operated jointly in Australia to track satellites in low earth orbit (LEO – up to 1,000 kms. altitude), missile launches from countries in the region, and, as a global public good, low earth orbit space junk. The recycled C-band radar is intended to give the ADF an opportunity “to grow an SSA capability”.22

The space radar is soon to be joined to a new space telescope. Space Surveillance Network radars can detect objects in geo-synchronous orbits (GEO) around 36,000 kms altitude to some extent, but searching in GEO is “time-consuming and difficult”, while telescopes can do so much more readily.23 At AUSMIN 2012 the two countries decided to deploy a highly advanced Space Surveillance Telescope (SST) built Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) from New Mexico to Australia.24

C-band radar in Antigua, before transfer to North West Cape C-band radar in Antigua, before transfer to North West Cape |

According to Pentagon officials, the Space Surveillance Telescope “will offer an order-of-magnitude improvement over ground-based electro-optical deep space surveillance, or GEODSS, telescopes [three of which are located on Diego Garcia] in search rate and the ability to detect and track satellites”.25 Also operating under the auspices of the US Joint Space Operations Center, the Space Surveillance Telescope will be “able to search an area in space the size of the United States in seconds” and “is capable of detecting a small laser pointer on top of New York City’s Empire State Building from a distance equal to Miami, Florida.”26

The SST will be particularly important for tracking satellites and space debris in geo-synchronous orbits, including micro-satellites. There are now a large number of Chinese military intelligence, communications, and global positioning satellites in geo-synchronous earth orbits (GEO). Blinding China’s space and air surveillance assets is a fundamental US task if US Navy carriers task groups are to operate in the East and South China Seas close to the Chinese coast. The Pentagon said ‘the Australians are in the process of selecting a site for the SST”, possibly at either North West Cape or Kojarena.27

Space Surveillance Telescope, Soccorro, NM;before transfer to WA site |

Pine Gap

The Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap outside Alice Springs remains the most important US intelligence base outside the US itself. In the classified the classified Force Posture Review prior to the 2009 Defence White Paper, the Defence Department confirmed it knows Pine Gap, the eyes and ears of the US military, is a high priority target in the event of US-China war.28

Pine Gap has two quite distinct functions, both of which are critically important to the United States.

Pine Gap’s main role concerns signals intelligence. It is a control, command and downlink ground station for satellites in orbits 36,000 kms above the earth collecting intelligence from all manner of electronic transmissions (signals intelligence) including missile telemetry, radars, microwave transmissions, cell phone transmissions, and satellite uplinks. As well as retaining its long-running strategic intelligence roles, the expansion and upgrading of Pine Gap has brought the facility into the heart of US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And now, of course into current military and CIA counter-terrorism operations, including the US of drones for assassination, in Pakistan, the Yemen, and Somalia.

Pine Gap, Google Earth, January 2013 |

Pine Gap’s second role since 2000 is as a remote ground station for US thermal imaging satellites, after it took over much of the work of the US base at Nurrungar in South Australia – detecting missile launches, jet fighters using afterburners, and even major explosions in war zones like Afghanistan. These satellites provide the US with early warning of missile attack, but they also provide the US with nuclear targeting data. Moreover, these thermal imaging satellites provide US and Japanese missile defence systems with crucial “cueing” information on the trajectories of incoming missiles, without which missile defence would be impossible.

For China the missile defence capacities of the United States and its East Asian allies threaten to vitiate its minimal nuclear deterrence force – 200 plus operational missiles vs. the US 1700 or so, with more than double that number in storage, and with far greater accuracy, reliability, deployment options, and design sophistication. We are already seeing the strategic consequences: Chinese missile modernization, missile defence counter-measures, and most likely, targeting of Pine Gap in the event of war. The Defence Department recognized that last fact, but only in a classified Force Posture Review conducted for the 2009 Defence White Paper.

Since May 2013, the role of Pine Gap’s principal, signals intelligence gathering and processing role has returned to the world’s front pages courtesy of the extraordinarily courageous whistle blowing by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. To cut a long story short, several aspects are highly relevant to our concerns here:

- Pine Gap, and the wider US global signals intelligence system of which it is a part, now integrates surveillance and monitoring of global internet and email traffic and mobile telephone use.

- Pine Gap undoubtedly has a major role in providing signals intelligence in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

- This has now extended to US counter-terrorism operations, including the provision of data facilitating drone strike targeting in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen in close to real time.

|

US and Australian human rights organizations have formally requested the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism to investigate the possible “complicity of Australian officials in civilian deaths caused by the US drone strikes”, thereby facilitating “targeted killing in violation of international humanitarian law and international human rights law.” Specifically the Special Rapporteur has been asked to examine “the ‘nature of co-operation’ between Australian and US officials in providing locational data used in targeting, and the basis on which any co-operation is lawful.”29

This last development brings us back to asymmetrical alliance cooperation and its consequences, including the reality behind the Australian government’s assertion that Pine Gap and North West Cape operate with its “full knowledge and concurrence”.30

In the case of Pine Gap, there is no doubt that the long struggle in the Hawke and Keating years to widen and deepen Australian involvement with the operations of Pine Gap, Nurrungar and North West Cape bore considerable fruit, symbolized in the appointment of Australians as deputy heads at Pine Gap and Nurrungar. This arrangement continues today at Pine Gap.

Without doubt, Australia is beneficiary of the intelligence product from Pine Gap’s signals intelligence and thermal imaging satellite monitoring functions. The degree to which that intelligence is significant, necessary, and irreplaceable for Australian strategic interests is quite a distinct issue. It is difficult to make an informed assessment of these matters, but former intelligence officers have distinguished between information that is highly salient, useful, and usable, and other information which they regard as nice to have, but may be simply a matter of the pleasures of being in the know globally.31

Almost fifty years after its establishment, and a quarter of a century after the end of the Cold War for which it was constructed, there are a number of aspects of Pine Gap that need urgent and deep debate in Australia. But let me confine myself here to three.

Australia, Pine Gap and Targeted Assassinations

The first is Australia’s involvement through Pine Gap in assassinations – formally speaking, “extra-judicial killings” – by US forces outside legally-constituted war zones, whether by drone or special operations forces. Prima facie, the Australian government is culpable under national and international law for illegal killings by US drones by supplying the requisite targeting data.

Pine Gap’s targeting contribution to what are illegal killings by the United States using armed drones immediately puts the Australian government the onus on the Australian government to explain its knowledge of these activities.

If indeed the Australian government does have “full knowledge” of Pine Gap’s role in these operations, including even a general knowledge of this activity, then its claim to “concurrence” must be presumed to be relevant under international law to extra-judicial killings by CIA and USAF drones, as well as by US Special Forces..

The response from the Defence Department to the letter to the UN Special Rapporteur was carefully framed and evasive, saying only:

“Australia works with the intelligence agencies of our close ally and closest partners to protect our country from threats such as terrorism. All such activities are conducted in strict accordance with Australian law.”32

Extra-judicial executions of foreign nationals outside combat zones such as Afghanistan (where such acts are mandated by UNSC Resolution 1846/2001, and its successors) are incompatible with the Australian criminal code and the Law of Armed Conflict in international law, to which the Australian Defence Force explicitly sees itself as subordinate.

The Australian government needs to explain the manner and extent to which Pine Gap is actually involved. It then needs to explain what knowledge it has of these matters. And then, it needs to ensure that any activities conducted at Pine Gap or any other facility are brought into line with international law.

This last may involve requiring the United States to cease and desist using the signals intelligence capacities of Pine Gap for this purpose, and/or withdrawing cooperation with the United States in such activities, if necessary, to the point of requiring the closure of the facility. Either way, the United States would need to expand rapidly the already substantial redundancies built into some, though not all of the systems of which Pine Gap is so vital a part, or to move to relocate the facility within a reasonable but not indefinite period.

The second issue brings us to the heart of the justifications offered by Australian governments for hosting Pine Gap. When it was first built in the 1960s, Pine Gap’s primary signals intelligence role was to gather telemetry transmitted after launch from Soviet missiles to their home bases – data that allowed the United States to understand the nature, purpose, and technical capacities of the missiles which might one day be used against it. The satellites controlled by and downlinking data to Pine Gap captured this telemetry from missiles traversing the eastern hemisphere, processing and analysing it, and sending it on to Washington. With the achievement of the early nuclear arms control agreements, this capacity became essential to the willingness of the United States to enter into such agreements with the Soviet Union, because it ensured detection of any deception or cheating by the Soviet Union with its subsequent missile development.

Accordingly, every government since the Hawke government has publicly justified Pine Gap by arguing that Australia relies on the maintenance of what it called “stable nuclear deterrence” between the US and the Soviet Union, and Pine Gap underpinned that stability by making it possible for the US to enter into verifiable arms control agreements. If you want stable nuclear deterrence, then you need verifiable arms control agreements, and so you have to accept Pine Gap. This assessment led Desmond Ball, the most knowledgeable Australian in both matters of US nuclear targeting plans and signals intelligence, to conclude that while he opposed Pine Gap’s deeply troubling role in nuclear targeting, Pine Gap was the one American base whose retention he supported, albeit with great reluctance and misgivings.33

My own feeling is that the situation has changed in several ways that should lead us to seriously rethink Pine Gap’s role in arms control activities.

The first is that the Cold War has ended. The Soviet Union has gone. Nuclear deterrence between the United States and Russia today is quite different from that in the Cold War, moving to what the deterrence theorist Patrick Morgan describes as “recessed deterrence” in which the underlying political purpose and salience of the two nations’ deterrence postures have all but disappeared.

The United States and China do have a nuclear deterrence relationship, but it is of a quite different nature – anything but balanced, with what the Chinese rightly call their minimum means of retaliation, and the US maintaining its massive nuclear superiority. There are worrying aspects of this relationship, but the point here is that compared with the US-Soviet balance, China is in a vastly weaker position regarding the United States, all the more so with its deterrent force almost equally concerned with India and Russia. I could also add the obvious systemic difference with the Cold War – notably the economic coupling of China, Australia and the United States. This economic interdependence does not of itself, as liberal theorists would have us believe, render war impossible, but it does mean that we are facing a situation more complex and unprecedented than the Cold War structure of containment and exclusive economic blocs.

But this raises a question: if Pine Gap’s arms control verification function is so important for the United States, what technological basis can China rely on for verification in arms control agreements with the United States? The Australian government insists it supports nuclear disarmament, and so would logically want both two countries to limit their nuclear weapons.

At present, Pine Gap supports unilateral arms control verification – verification by the United States of its adversaries’ capacities, including those of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, as well as those of India and Pakistan. But this is an interest that the United States – and Australia – shares with China, which does not have anything like Pine Gap’s capacities. Moreover all three share that interest with the 30 plus countries that have substantial ballistic missile capacities – and their neighbours. Australia wants North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile program, and Pine Gap certainly is involved in intercepting telemetry from DPRK missile tests, as well those in India and Pakistan.

It is time we started asking about the utility of the information Pine Gap collects on such matters for the wider human interest – including the 180 or so countries that are not nuclear weapons states but would be deeply affected by nuclear use.

My own position is that while there are some important gaps in our technical knowledge of Pine Gap and the global US intelligence systems of which it is technologically and organisationally a crucial part, there is much that we do know that permits us to make even preliminary judgments on these questions, and which should set the direction of urgent policy development by a new generation of Australian and international researchers.34

Let me finish by re-connecting these comments on the bases with the national discussion concerning the alliance between Australia and the United States, thinking in broad terms about what Australia should and should not be doing.

Australia and a Global NATO

What should Australia not do about the American alliance today?

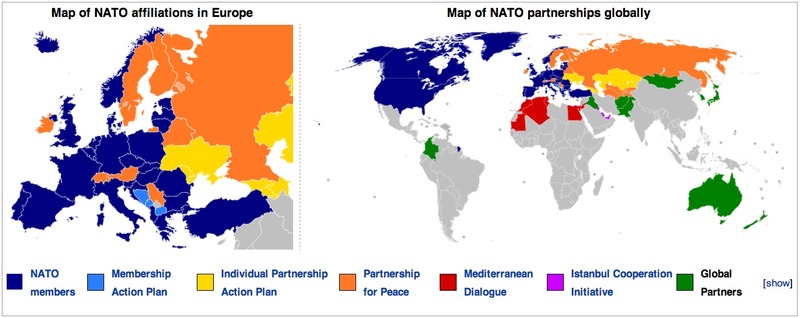

We should not join the incipient extension of NATO via strategic partnership (and shared operational experience in Afghanistan) building into what might be called Global NATO. NATO’s own crisis of post-Cold War identity and purpose should not be unthinkingly resolved by extending a Cold War North Atlantic alliance to the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Source: NATO, Wikipedia. |

We should not rush to deepen the already extensive military and intelligence cooperation with Japan through a comprehensive defence treaty of mutual defence.35 Australia shares many interests with Japan in Northeast Asia, but it also shares a good number of interests with Japan’s neighbours, South Korea and China, with whom Japan is at present in deeply serious conflict over territorial and historical issues derived from Japan’s failure to transcend its imperialist past. Japan under the Abe regime has the most nationalistic government since 1945 – one, that thinks of itself as a restorationist government, transcending what it regards as the ignominy of the US-sponsored – and popularly embraced – “post-war regime” as signalled most clearly by its program for radical constitutional revision.36

HMAS Sydney at Yokosuka Naval Base, Source. |

We should not repeat the errors of unthinking participation in the United States wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, neither of which served Australian strategic interests, and both of which have ended, after huge expenditures of blood and treasure and enormous toll in Afghan and Iraqi life, as enormous political failures. As many argued correctly at the time, the appropriate and effective response to Al Qaeda’s transnational terrorism was a globally coordinated intelligence and police apparatus of cooperation against criminals. As many argued rightly at the time, the intelligence about weapons of mass destruction on which the Iraq invasion was based was both wrong and falsified. What has not yet been fully absorbed from the Iraq lesson, and which is being occluded again in the case of Syria, is the profound dysfunctionality of the world order that permits some countries to possess nuclear weapons but insists, even at the precise instance of initiating aggressive wars, that other countries may not be permitted to do so. This makes clear the connection between, on the one hand, the issue of moving to a world without nuclear weapons, where the eight nuclear powers’ geo-political impunity of possessing nuclear weapons, and on the other, Australia’s niche role on one side of arguments for intervention in the name of nuclear non-proliferation.37

So what should Australia do about the American alliance today?

Much of what I have said about the place of United States military and intelligence bases in Australia points to the need for a re-balancing of the American alliance. In recent years, the combination of Australian enthusiasm for US wars and expanded American role definition for niche allies, with the mantras of interoperability and shared global strategic interests has pushed the alliance into a misplaced hyper-integration. Re-balancing will involve once again assessing the strategic grand bargain made on behalf of Australians by their governments, without public debate and acknowledgment, under which US military and intelligence facilities, with their concomitant strategic dangers and political costs. These have been accepted in return for Australian access to higher levels of US military technology than comparable allies such as Japan, access to intelligence otherwise likely to be denied, and a seat at the table where decisions are made in Washington. Whether that seat comes with a speaking role, whether that intelligence is necessary and irreplaceable, and whether that military technology is necessary and only available from the United States are part of the assessment of the appropriate point of balance for the alliance as a whole.

Redefining Australian National Interests and Global Human Interests

The primary requirement is a fundamental debate about defence and the security of Australia, where key issues are the identification of both Australian national interests and Australians sharing of global human interests. The four most dismaying aspects of security debates in this country in recent decades have been

- the narrow range of participants, with Defence White Papers ushered in with a mockery of community consultation;

- a profound inability of the Australian security community to conceive even on a hypothetical basis of Australian defence absent the American alliance;

- a deep-seated related difficulty with identifying specifically Australian national interests, potentially independent of those of the United States; and

- an underdeveloped analysis of security and threat to the Australian people that leads to a privileging of conceptually and evidentially distant military threats combined with a tokenistic approach to more realistic threats from non-military sources, above all climate change, infectious diseases, poverty, and predatory globalisation.

This should be accompanied by a broad and undoubtedly troubling discussion of our relationship to possible conflict between the United States and China, and specifically why the default setting of Australian defence policy is against China. This is by no means to advocate anything like a replacement of one with the other, but rather to begin to explore and tease out the very different elements that have led us to this point, and what might be done to generate a more sustainable national consensus. Australians, more multiculturally diverse than they were half a century ago, remain the cultural children of European settler colonialism, nationally born in the historically anomalous era of Chinese subordination. As Hugh White has usefully emphasized, Australians find the idea of Asia, including Austral-Asia becoming a Chinese sphere of influence – in fact the civilizational norm – something which is inherently unsettling.38

Australia and Indonesia

One final thing Australia should do concerning the alliance with the United States is to complement a re-balancing of the American alliance with a substantial and sustained transformation of Australia’s relationship with Indonesia. The primary driver of Australia’s compulsive longing for protection by distant imperial powers apart from the genocide of indigenous Australians that permitted settler colonialism, is the fear of “Asian hordes to our north”. Geography means that Indonesia is always a primary candidate for such projections. It is a commonplace now to remark on the distortions and failings of that relationship, which is asymmetric, volatile, uneven, hemmed in by social distance and cultural ignorance, and dominated by government-government connections. Despite proximity and increasingly shared interests, shared, business linkages are thin, and civil society linkages thinner still.39 Australian media- and education-derived knowledge of Indonesia is minimal and distorted, and with the collapse of Indonesian studies in Australia, becoming more so. Australian political leaders seem addicted to abrupt and short-sighted policy formulation that either affects Indonesian legitimate interests or depends on Indonesian cooperation – often without even a fig leaf of respectful advance consultation.

Geography dictates that Indonesia will always be a core Australian defence concern. In the Sukarno era Australian defence planning about Indonesia was dominated by geo-strategic fears. In the Suharto era, remnant concerns of this type were subordinated to abject Australian accommodation of the New Order despite knowledge of its extreme costs in terms of human rights and human security in Indonesia’s centre, its peripheries, and in its Timorese colony.

There is much about democratised Indonesia that still gives pause on the human rights and human security agenda – particularly the Yudhoyono administration’s inability to control elements of the military in Papua, predatory power structures, dysfunctional elements in government, the repression of profound historical trauma within living memory, and the odour of government toleration of murderous religious intolerance.

Yet a great deal has also changed, and it is now clearer than ever before that Australians share many interests with Indonesians. Australians need to add into their considerations about a re-balancing of the American alliance the question of what will be involved in moving Australia and Indonesia towards a relationship based on shared interests and values. It may well be too early to talk of the two countries forming a security community, where problems and disagreements will be resolved peacefully and cooperatively. But we can have some confidence we can do better than the present.

The bold 1995 Australia-Indonesia security agreement was subverted by its unwillingness to acknowledge the terror both at the heart of the New Order and its ongoing colonial project in East Timor, as well as by the Howard government’s triumphalism following the INTERFET intervention in East Timor to end the terror by Indonesian troops and their local militia following the UN-auspiced vote for East Timorese independence from Indonesia. But the clearly articulated promises of the 1995 agreement remain as desirable today as they are unfulfilled, with aims to:

“consult at ministerial level on a regular basis about matters affecting their common security and to develop such cooperation as would benefit their own security and the region; consult each other in the case of adverse challenges to either party or to their common security interests and, if appropriate, consider measures which might be taken either individually or jointly and in accordance with the processes of each Party; promote – in accordance with the policies and priorities of each – mutually beneficial cooperative activities in the security field in areas to be identified by the two Parties.”40

In the longer run a bilateral or multilateral security community, built on an understanding of shared problems and an imperative of genuinely understood shared need for cooperative security, is surely what needs to be thought about. What would it take to move Australia and Indonesia to the point where they constitute an at least preliminary or nascent security community? A suite of difficulties, obstacles, blind spots, and possible missteps come readily to mind, and there is much that has to be talked about, probably with some difficulty, but this may well be the most important task for an Australian community wide debate about a pathway to a defensible Australia.

These are not simply Australian issues – they are rather just the particular inflections of problems of autonomy faced by all US allies and countries hosting US military facilities, but especially by those in Asia and the Indian Ocean and the Middle East. Part of the particularly Australian problem has been the inability to see the world in non-imperial terms. Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s keynote address to the Shangri-La Security Dialogue in 2012 made a strong case for regional cooperative security. Recalling the “time when Southeast Asia was ripped apart by extra-regional powers”, Yudhoyono said “the US and China have an obligation not just to themselves, but to the rest of the region to develop peaceful cooperation.”41 Yudhoyono’s call for cooperative security was a rearticulation of Indonesia’s foreign policy principle of mendayung di antara dua karang or “rowing between two reefs” – originally formulated around the time Australia established its alliance with the United States at the beginning of the Cold War. But the Indonesian president was followed by US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta who announced the US was back in the region, and back for good.42 Yudhoyono’s history lesson is relevant to more than Australia.

Richard Tanter is a Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute and teaches in the School of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Melbourne. A Japan Focus associate, he has written widely on Japanese, Indonesian and global security policy, including ‘With Eyes Wide Shut: Japan, Heisei Militarization and the Bush Doctrine’ in Melvin Gurtov and Peter Van Ness (eds.), Confronting the Bush Doctrine: Critical Views from the Asia-Pacific, (New York: Routledge, 2005). His most recent book, co-edited with Gerry Van Klinken and Desmond Ball, is Masters of Terror: Indonesia’s Military and Violence in East Timor in 1999 [second edition]. His website can be found here, and he may be reached by email here.

Notes

1 Originally titled “Lily pads and networks: the implications of Northern Australian integration with US strategic planning” for presentation at the symposium organised by The Northern Institute of Charles Darwin University on Defending Australia: the US Military Presence in Northern Australia, Parliament House, Darwin, 23 August 2013. My thanks to the Institute and its director, Professor Ruth Wallace, for the invitation to participate in the symposium, and to those participating in the subsequent discussions. I am grateful, as ever, to Mark Selden for his patient and constructive editing. I am also grateful to Malcolm Fraser for stimulating argument and discussion of many of the issues in this paper. Detailed documentation of certain sections of this talk is available in Richard Tanter, The Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012.

2 Captain David C. Chandler, Jr., “‘Lily-Pad’ Basing Concept Put to the Test”, Army Logistician, PB 70005-2 Vol. 37, March-April 2005.

3 Lauren Ploch, Africa Command: U.S. Strategic Interests and the Role of the U.S. Military in Africa, Congressional Research Service, 22 July 2011, pp. 9-10.

4 “Tomgram: Nick Turse, AFRICOM’s Gigantic ‘Small Footprint’“, TomDisptach.com, 5 September 2013.

5 Nick Turse, “Empire of Bases 2.0. Does the Pentagon Really Have 1,180 Foreign Bases?” Tomgram: The Pentagon’s Planet of Bases, TomDispatch.com , 9 January 2011.

6 Department of Defense, Base Structure Report FY 2013 Baseline.

7 Chalmers Johnson, The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic, (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004).

8 For details see the careful review for study conducted for the Pentagon by the RAND Corporation: Michael J. Lostumbo et al, Overseas Basing of U.S. Military Forces: An Assessment of Relative Costs and Strategic Benefits, Report Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, RAND Corporation, 2013.

9 Hilary Rodham Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century”, Foreign Policy, 11 October 2011.

10 For an elegant exploration of just how primitive these approaches are, see Steve Chan, China, the US, and the Power-Transition Theory, Routledge, 2009.

11 The current parties to the negotiations are Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the US and Vietnam.

12 See Ganeshan Wignaraja, “Why the RCEP matters for Asia and the world”, East Asia Forum, 15 May 2013; and Demetri Sevastopulo, Shawn Donnan, and Ben Bland, “Obama’s absence boosts China trade deal”, Financial Times, 15 October 2013.

13 Despite much commentary, there is remarkably little sustained and informed discussion of Australian strategic options. The most important recent reflection remains Hugh White’s 2010 Quarterly Essay “Power Shift: Australia’s Future between Washington and Beijing”, Quarterly Essay 39, September 2010. Prior to that, three key contributions still relevant today are the Review of Australia’s Defence Capabilities (the 1986 Dibb report, reflecting earlier conceptual work by Dibb, Desmond Ball, J.O. Langtry, and Kim Beazley); Ball’s own highly condensed argument in his “The Strategic Essence”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2001; and David Martin’s maverick but central 1984 contribution, Armed Neutrality for Australia, Dove Communications.

14 On the Vietnam case see Michael Sexton, War For the Asking: Australia’s Vietnam Secrets, Penguin, 1981, and subsequent debate. This includes the official history by Peter Edwards, Crises and Commitments, Allen & Unwin, 1992; and a number of interventions by Gary Woodard, including his “Asian alternatives: Going to war in the 1960s”, Public lecture for the National Archives of Australia, presented in Canberra, 30 May 2003.

15 See Craig Whitlock, “US, Australia plan expansion of military ties amid pivot to SE Asia”, Washington Post, 26 March 2012; and Brendan Nicholson, “US seeks deeper military ties”, The Australian, 28 March 2012.

16 Australia-United States Exchange of Letters Relating to Harold E. Holt Naval Communications Station, AUSMIN 2010, Department of Foreign of Affairs and Trade. For discussion of the phrasing see Richard Tanter “North by North West Cape: Eyes on China”, Nautilus Institute, Austral Policy Forum 10-02A, 14 December 2010.

17 For details see Richard Tanter, “After Obama – The New Joint Facilities”, Arena Magazine, May 2012; and Richard Tanter, The “Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012 (abridged earlier version appeared as “American bases in Australia revisited”, in Brendan Taylor, Nicholas Farrelly and Sheryn Lee (eds.) Insurgent Intellectual: Essays in honour of Professor Desmond Ball, (ISEAS, December 2012), found here.

18 Admiral Jonathan W. Greenert, Chief of Naval Operations and General James F. Amos, Commandant of the Marine Corps, “The Future of Maritime Forces”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 11 July 2013.

19 To take one example, from the Howard years, see the Ministerial Statement on the Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap made by the then Defence Minister, Brendan Nelson, on 20 September 2007.

20 “New $927m satellite boosts defence network”, AAP, The Australian (8 August 2013); and “The $927 million US satellite you funded launches off from Cape Canaveral in Florida”, AAP, Perth Now (8 August 2013).

21 Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt (North West Cape), Australian Defence Facilities Briefing Book, Nautilus Institute.

22 JP 3029 Integrated Capability Network Infrastructure, Phase 1 Space Surveillance, Defence Capability Plan 2012 (Public Version), Department of Defence, pp, 166-7; “Don’t touch their junk: USAF’s SSA tracking space debris”, Defense Industry Daily (updated 15 August 2013); USA Moves Ahead with Next-Generation “Space Fence” Tracking, Defense Industry Daily (updated 14 November 2012); and Basing of first U.S. Space Fence facility announced, U.S. Air Force, (25 September 2012).

23 Global Space Situational Awareness Sensors, Brian Weeden et al, Secure World Foundation, AMOS 2010, p. 8.

24 Space Surveillance Telescope (SST), Tactical Technology Office, DARPA.

25 U.S. to Locate Key Space Systems in Australia, Defense Aerospace.com, (US Department of Defense media release, 14 November 2012).

26 DARPA telescope headed to Australia to help track space debris, Nanowerk News (19 November 2012).

27 United States and Australia Advance Space Partnership, News Release, Department of Defense, No. 895-12 (14 November 2012); and “Australia-Based U.S. Radar To Watch China Launches”, Bradley Perrett, Aviation Week & Space Technology (25 March 2013).

28 David Uren, The Kingdom and the Quarry: China, Australia, Fear and Greed, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2012), p.128: “Part of the defence thinking is that in the event of a conflict with the United States, China would attempt to destroy Pine Gap…”. See Richard Tanter, “Possibilities and effects of a nuclear missile attack on Pine Gap”, Australian Defence Facilities, Nautilus Institute, 30 October 2013. For further discussion see Richard Tanter, The Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012, pp. 41 ff.

29 The organizations involved are the Australian office of the New York-based Human Rights Watch, and Human Rights Law Centre in Melbourne. See Oliver Laughland, “Pine Gap’s role in US drone strikes should be investigated – rights groups”, The Guardian (19 August 2013); and Joint Letter from Human Rights Watch and Human Rights Law Centre to Ben Emmerson, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 16 August 2013.

30 For example, see the reply by Senator John Faulkner, Minister of Defence to a question from Senator Scott Ludlam: “The activities at the Pine Gap facility take place with the full knowledge and concurrence of the Australian Government.” Defence: Pine Gap, Question on Notice 2495, The Senate, 23 February 2010, Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates.

31 The Australian Navy in particular values regional ship-to-ship missile launch surveillance capacities through the Remote Ground Station for SBIRS and DSP satellites, directly through the ADF’s own ground terminals at the northern edge of Pine Gap. Intelligence analysts who have left government have talked in general terms of the very large quantity and significant quality of intelligence Australia receives from being in the UKUSA Five Eyes club, much if not most of which Australia would not receive in the absence of the agreements to host Pine Gap in particular.

32 Oliver Laughland, “Pine Gap’s role in US drone strikes should be investigated – rights groups“, The Guardian, 19 August 2013.

33 Desmond Ball, Pine Gap: Australia and the US Geostationary Signals Intelligence Satellite Program, Sydney: Allen and Unwin Australia, 1988.

34 The technical basis for this argument is spelled out in the last sections of Richard Tanter, The Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012.

35 Richard Tanter, “A question of accountability as HMAS Sydney joins USN Carrier Strike Group”, Campaign for an Iraq War Inquiry, 20 May 2013.

36 C. Douglas Lummis,”It Would Make No Sense for Article 9 to Mean What it Says, Therefore It Doesn’t. The Transformation of Japan’s Constitution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 39, No. 2, September 30, 2013.

37 See Why Did We Go to War in Iraq? A call for an Australian inquiry, Campaign for an Iraq War Inquiry, here.

38 Hugh White, The China Choice, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2013).

39 For further argument see Richard Tanter, “Shared problems, shared interests: reframing Australia-Indonesia security relations”, in Jemma Purdey (editor), Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of Self, Discipline and Nation, (Monash University Press).

40 Text in Appendix A of Gary Brown, Frank Frost and Stephen Sherlock, “The Australian-Indonesian Security Agreement – Issues and Implications”, Parliamentary Library Research Paper 25 – 1995-96, Parliament of Australia.

41 Dr H Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, “An Architecture for Durable Peace in the Asia-Pacific“, Shangri-La Dialogue 2012 Keynote Address, 1 June 2012.

42 Leon Panetta, “The US Rebalance Towards the Asia-Pacific“, Shangri-La Dialogue 2012 First Plenary Session, 1 June 2012.

– See more at: http://japanfocus.org/-Richard-Tanter/4025?utm_source=November+11%2C+2013&utm_campaign=China%27s+Connectivity+Revolution&utm_medium=email#sthash.7I34x2fo.dpuf