The US-Kenya Bilateral Free Trade Agreement. Garbage In, Garbage Out

Washington hopes a free trade pact with Kenya will give it a beachhead in its hot war with Al-Shabab and cold war with China—and an African dumping ground for GMOs and plastic waste. What Kenya gets in exchange is not at all clear.

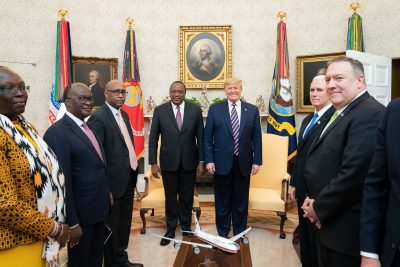

The United States and Kenya have been negotiating a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) since March 2020, sparking concerns about further neocolonization of the East African state by Washington, whose economy is 224 times the size of Kenya’s. Given its “America First” policy, it is not surprising the Trump administration would aim to subjugate Kenya economically through this FTA, as a template for the rest of Africa.

Somewhat more puzzling is why the Kenyan government of President Uhuru Kenyatta would go along with it, and what Trump’s successors in the Biden administration will do with the negotiations now. I spoke to Kenyan and U.S. trade experts about the domestic and geo-politics behind the FTA.

“The Trump administration wanted to move away from preferential trade programs towards more ‘reciprocal’ trade in which developing countries must make new concessions to keep the trade benefits they have now,” says Karen Hansen-Kuhn, program director at the Washington-based Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP). “This agreement would be based on the model established under the new NAFTA [known as USMCA], which sets new limits on governments’ abilities to set rules on things like pesticides and GMOs or other public interest rules. In general, it would serve to cement these new limits on public policy in both the U.S. and Kenya against more progressive rules in the future.”

As a major participant in the U.S. Africa Command’s (AFRICOM) security operations on the continent, especially in Somalia, Kenya is already a leading U.S. client state, accepting $824 million in military and economic aid from Washington in 2018. Since 2010, Kenya has received $400 million in counterterrorism funding from the Pentagon and has become the U.S. military’s main foreign conduit for opposing Al-Shabab, the insurgent group that is fighting the U.S. in Somalia for control of the Horn of Africa. Al Shabab also carries out attacks in Kenya, including strikes last January on a U.S. military base and two schools near the Somali border.

As in Brazil, the United States sees strong military co-ordination with Kenya in combination with a preferential free trade pact—the U.S. government’s first with a sub-Saharan country—as a way to shore up Nairobi as a dependable military and economic conduit for U.S. interests on the continent.

Another major factor for Washington in seeking the FTA is countering Chinese influence in Africa, which has grown dramatically in economic terms. In fact, this may be “foremost among Washington’s concerns,” according to the U.S. establishment think-tank the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). China–Africa trade has “soared” since 2008 while trade between the continent and the U.S. has declined, notes CFR. China is also the top investor in Africa. Kenya’s imports from China were worth $3.79 billion in 2017, making Beijing its leading trade partner whereas imports from the U.S. in 2019 were $401 million and exports to the U.S. were $667 million.

*

A main objective for the U.S. in the Kenyan FTA negotiations is gaining tariff-free access for its dominant agricultural sector, which could potentially destroy Kenya’s domestic food systems. This is one reason why Public Citizen, the U.S. consumer advocacy organization, calls the FTA “a terrible idea.” Melissa Omino, research manager at the Center for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law (part of Swarthmore University in Nairobi, Kenya), agrees there would be “dire consequences” for Kenya stemming from the FTA, particularly concerning food security.

“The U.S. heavily subsidizes its own domestic producers thus allowing them to overproduce. When such goods are exported out of the U.S. at low prices together with removed tariffs, it results in the flooding of such U.S. agricultural exports leading to the destruction of the domestic market of Kenya,” says Omino. The U.S. also wants Kenya to import its GMO corn and maize, but GMO products are banned in Kenya currently.

According to Omino, the effect of the FTA would become devastating when world food prices go up, since Kenyans would neither be able to afford to buy food imports nor would they have local production to rely on.

“An example of this is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now USMCA), which affected Mexico such that [two million] corn farmers lost their income due to flooding of corn from the U.S.,” she tells me. “So far Kenya has been protected by the tariffs of the East African Community [EAC—a regional trade agreement Kenya is part of along with five other countries] and has been able to manage food security well. Once these are removed the case changes drastically.”

Melanie Foley, international campaigns director of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, pointed out to me that in the proposed FTA, the U.S. is also targeting Kenya’s “strong laws” banning certain GMO foods, protecting consumers’ privacy online, and the country’s progressive environmental policies such as its ban on plastic bags. Kenya is a leader in the area of plastic waste bans and management, according to Omino.

Foley quotes a New York Times exposé, according to which, she says,

“the [American] petrochemical lobby is pushing the U.S. government to use these talks to challenge Kenya’s strong plastics laws and expand the plastics industry’s footprint across Kenya and the continent. If the industry has its way, Kenya’s strong plastic bag ban and proposed limits on imports of plastic garbage could be under threat.”

James Gathii, professor of law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, tells me that the flooding of the Kenyan market with U.S. GMO corn and maize will not only devastate Kenyan agriculture but also its industry.

“Heavily subsidized farm products from the U.S. flooding the Kenyan market would enhance access to Kenya for U.S. companies in a way that would undermine Kenya’s industrialization plans, especially in agro-manufacturing.”

Gathii, a leading Kenyan academic and an expert in international trade law, says he is also concerned that Washington “is aiming for enhanced intellectual property protections” in the Kenya FTA, which could inhibit access to essential medicines and likely “undermine the fledgling health care systems in Kenya’s regional governments.” It is common United States Trade Representative practice to use trade negotiations to solidify and extend monopoly patent and other intellectual property protections for Big Pharma, Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

“Counties have made a lot of progress in bringing health care closer to the people at the grassroot level for the first time since Kenya’s independence in 1963,” continues Gathii. “That progress will be upended by the U.S.–Kenya FTA that would make it difficult if not impossible to preserve and enhance the work these counties have been able to do with provision of essential drugs and health care systems that would face higher drug and medical costs as a result of the FTA.”

*

Sharon Treat, senior attorney at IATP, emphasizes the degradation of standards Kenya faces under an FTA with the U.S. Currently Kenya has a trading relationship with the European Union and “must align its food standards to be consistent with EU standards in order to export there,” she explains.

“EU food standards in many respects are more protective of human health or the environment than U.S. standards, for example, allowable levels of pesticide residues on produce, approvals of genetically modified food for human consumption, and use of chemical additives and growth promoters such as ractopamine and hormones in livestock production.” Treat warns that a trade deal with the U.S. “could lead Kenya to adopt policies that reduce, rather than increase environmental and other protections.”

The Kenyan government argues that it needs the FTA to safeguard against possible U.S. cancellation of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which currently provides considerable U.S. market access for Kenya and other African countries and has to be renewed by the U.S. Congress in 2025. But as Foley points out, the AGOA is unlikely to be terminated in 2025 as it “is extremely popular in Congress” with both Democrats and Republicans.

“AGOA has been renewed twice with overwhelming bipartisan support,” she says. “[T]here is simply no reason to believe that Congress would not renew this popular program again before it expires in 2025.”

Given all the disadvantages of finalizing an FTA with the U.S. as opposed to staying with the AGOA, which requires no concessions from Kenya, the Kenyatta government’s devotion to the FTA talks is difficult to understand, says Omino.

“What makes it even more difficult to understand is that such negotiations take place in secrecy and the text is only released to the public after the parties have agreed and signed the same,” she adds. “This means that citizens of the affected countries…are not really in the know of motivations for and actual machinations within these negotiations.”

Gathii says it seems Kenya’s elite are “pegging their hopes on a trade and investment deal that will propel Kenya’s economy.” He adds,

“There is simply no empirical evidence that merely entering into a trade and investment agreement along the lines that the U.S. and Kenya are entering into can result in the kinds of economic gains that the Kenyan government hopes to garner.”

Incoming U.S. President Joe Biden will announce his administration’s trade policy at the end of January. On the one hand, he is widely expected to put a hold on new trade initiatives while focusing attention on domestic affairs including the still worsening COVID-19 outbreak as well as economic renewal projects, some of them tied to a climate transition.

At the same time, Biden is on record calling for “a united front of friends and partners to challenge China’s abusive behavior.” Going along with Trump’s FTA negotiations with Kenya, as Biden is expected to do with a proposed U.S.–U.K. FTA, could provide him with an easy bi-partisan win while appeasing establishment hawks, business Democrats and big business lobbyists in D.C. What is the livelihood of a million Kenyan farmers and food vendors next to that?

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Asad Ismi covers international affairs for the Monitor.

Featured image is a White House photo