The UK Signed Up in Secret to Support Saudi Military Action against Yemen. New Documents

More secrecy won’t protect Yemeni or Saudi Arabian civilians — or the British citizens at work behind the front line

Featured image: Royal Saudi Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon (by RA.AZ, CC BY-ND-SA 2.0)

Some birthdays are not for celebrating. Last month Yemen’s civil war slipped into its fourth year. It’s a war without obvious good or bad guys: Security Council investigators have documented violations of international humanitarian law by all sides. UN human rights officials nonetheless claim that the “leading cause” of civilian casualties are airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition, which backs Yemen’s President Hadi against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels and allied supporters of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh. The coalition’s air operations may not be any more indiscriminate or lacking in precaution than Houthi artillery and missile attacks, but are certainly more powerful and widespread.

What is Britain’s involvement in a war the UK government itself calls the world’s largest humanitarian crisis? Limited, if ministers are to be believed.

Throughout the Yemen conflict, Saudi Arabia has remained by far Britain’s leading arms export customer. Half of all UK exports of weapons and military equipment from 2013 to 2017 went to the Kingdom (up from 28% in 2007–11). Most were for the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF), 151 of whose 324 combat aircraft are British-supplied, along with weapons, ground systems, parts and spares.

Faced with inevitable legal and political criticism, the UK government insists that it isn’t responsible for — and cannot even necessarily know — how UK-supplied weapons are used after they have been shipped. Last July the High Court agreed (though activists are now applying to appeal that decision).

The reality of the UK’s relationship with the Saudi military challenges this ‘flog and forget’ theory of arms control. Under a sequence of formal agreements between the UK and Saudi governments since 1973, the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) and its contractors supply not only military ‘hardware’, but also human ‘software’. Around 7000 individuals — private employees, British civil servants and seconded Royal Air Force personnel — are present in Saudi Arabia to advise, train, service and manage British-supplied combat aircraft and other military equipment.

Ministers have nonetheless assured Parliament that these support staff are strictly hands-off:

Likewise they insist that neither UK military personnel nor contractor personnel “are involved in the loading of weapons for operational sorties, nor are they involved in the planning of operational sorties”.

Documents and testimonies we’ve gathered paint a more complicated picture. Over the past eighteen months, with the support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, Katherine Templar and I have sought to map these British and British-employed personnel in Saudi Arabia, trying to understand their work and their experiences. Though their existence is hardly a secret, their precise numbers and functions have long remained obscure. The UK-Saudi agreements that govern their work are classified ‘UK Confidential/RSAF Secret’ and are closed from public release until 2027. Even UK ministers say

they “do not have full visibility of the prime contractor’s manpower footprint in Saudi Arabia, the detail of which forms part of the commercial arrangements underpinning the delivery of much of the contracted support and is therefore sensitive.”

We’ve interviewed technicians, managers and officials from every level of this UK-Saudi ‘footprint’, backed up by individuals’ written CVs and formal job descriptions. If they are no longer physically loading bombs, as ministers insist, they’re still required to do almost everything else. A mix of UK company employees and seconded RAF personnel have continued to be responsible for maintaining the weapons systems of all Saudi Tornado IDS fighter-bombers, a backbone of the Yemen air war. They also work as aircraft armourers and weapons supervisors for the UK-supplied Typhoon fighters deployed at the main operating bases for Saudi Yemen operations, and provide deeper-level maintenance for Yemen-deployed combat aircraft.

These roles are underpinned by UK military commitments to Saudi Arabia that have never been disclosed to public or parliament. Our report discloses one of them, from a UK-Saudi agreement named ‘Al Yamamah’, which details how the UK will supply and support Saudi Arabia’s Tornado fighter-bombers. MOD officials have confirmed that this secret 1986 agreement continues in force “as long as the programme lasts”, despite more recent accords. (When in 2006 the UK’s Guardian newspaper obtained an earlier, less detailed agreement which had been released “by mistake” to the National Archives at Kew, the MOD removed the files overnight, and claimed their release “severely dented [Saudi] confidence in the [UK’s] ability to protect sensitive information”).

Prime Minister’s Office file PREM 19/3076 released to the National Archives during 2017 (Crown Copyright, reproduced under Open Government Licence v.3.0)

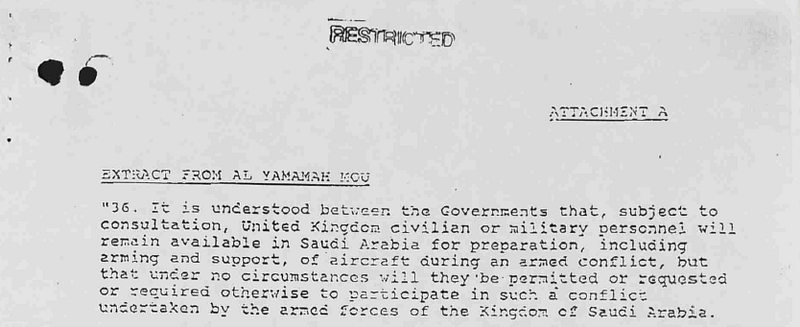

A similar inadvertent indiscretion seems to have been repeated: though the files containing the ‘Al Yamamah’ agreement remain withheld from public view, a bundle of unrelated Downing Street files, recently placed unnoticed in the National Archives, contains key extracts of the agreement.

As these papers show, the agreement requires that “United Kingdom civilian and military personnel will remain available in Saudi Arabia for preparation, including arming and support, of the [Tornado fighter-bomber] aircraft during an armed conflict” in which Saudi Arabia is involved, though these personnel may not “participate” in the conflict directly. The clause makes no reference to the authorisation or lawfulness of such a conflict.

British diplomats were concerned about the implications of this commitment from the start, lobbying within Whitehall during negotiations for the clause to be removed. “At worst”, the Foreign Office’s Middle East Department wrote to the MOD’s defence sales division, “this [clause] could expose HMG to accusations that they were involved in an undercover role in any number of types of unlawful military adventures; at best, it might threaten to compromise British neutrality in armed conflicts between third States.” Papers elsewhere in the National Archives show that the commitment was removed from a draft version of the agreement circulated within Whitehall six weeks before signature. It nonetheless seems to have been re-inserted into the final agreement at the last minute.

Extract of the 1986 UK-Saudi ‘Al Yamamah’ Memorandum of Understanding, included amongst papers in file PREM 19/3076 in the UK National Archives (Crown Copyright reproduced under Open Government Licence v3.0)

It’s difficult for the UK government to argue that it cannot know much about how its arms supplies are used, when it is helping the Saudi armed forces to use them. Our research doesn’t judge the rights or wrongs of the war in Yemen. But Britain’s day-to-day involvement with these weapons systems gives it a duty of precaution to help prevent civilian harm from those weapons. The government also has a duty of care for the thousands of British citizens at work in Saudi Arabia in quasi-military roles, fulfilling UK MOD contracts but as employees of private companies, without some of the legal and physical protections of military personnel or public servants. Most of the individuals we spoke to described their time in Saudi Arabia as amongst the most professionally and financially rewarding experiences of their lives. But we also spoke with whistle-blowers left unprotected under Saudi Labour Law, and even deprived of their British passports while working (a practice which seems now to have ended). We met contractors who described occasional physical jeopardy, from Scud missiles to unexploded ordnance. And we interviewed technicians anxious about the legal ramifications of their work within a foreign military machine at war.

The legal protection of these British citizens may be bound together with the physical protection of Yemen’s citizens. How the UK government navigates its obligations to protect both groups depends partly on whether other UK-Saudi agreements contain similar commitments to support Saudi combat operations, including the 2005 ‘Al Salam’ agreement covering UK support for the Saudi Air Force’s Typhoon fighters, and a new ‘Military and Security Cooperation Agreement’ signed in September 2017. (Both remain secret).

Nonetheless the government has clearly declined so far to exercise one option: to activate the ‘suspend’ clause in the Al Yamamah MOU. This all-or-nothing clause, also reproduced in the papers sitting unnoticed at the National Archives, allows the UK government “in the case of the outbreak of war… after consultation with the Saudi Arabian government…[to] suspend the arrangements provided for in the MOU”, removing UK re-supply and support for these weapons systems until the end of the conflict.

The diplomatic and economic fallout from such a suspension shouldn’t be taken lightly. But as bombardments continue on both sides of the Yemen-Saudi border, this is a question that should at least be debated in public, not behind closed doors in Whitehall and Riyadh.

Read the full research here.

*

Mike Lewis is a researcher on armed conflict, weapons, tax and illicit finance, a former UN Security Council sanctions investigator and an independent research consultant. He is writing in a personal capacity.